Journalist Karl Malakunas never imagined that a planned 700-word article on eco-tourism in the Philippine province of Palawan would turn into a 90-minute documentary that followed activists around the island as they tried to defend its natural resources amid deadly threats.

To continue watching, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Much less did he ever expect the documentary, titled Delikado (Tagalog for “dangerous”), to be included in the list of nominees for outstanding investigative documentary for the 44th News and Documentary Emmy Awards which was released on 28 July.

Although Malakunas has been a journalist for more than three decades, he started focusing on environmental issues in 2009 when he was Asia-Pacific environmental editor and Philippines bureau chief for global news agency Agence France-Presse (AFP). Delikado is his first crack at film-making.

The inspiration for the film came in 2011 when the Filipino activist he was speaking to for the story on eco-tourism in Palawan was murdered before Malakunas could even meet him in person.

Palawan is known as the Philippines’ last frontier for its hundreds of flora and fauna species, but it is also because of this rich biodiversity that it has been under constant threat from illegal logging, mining, and quarrying, mostly backed by big business and politics.

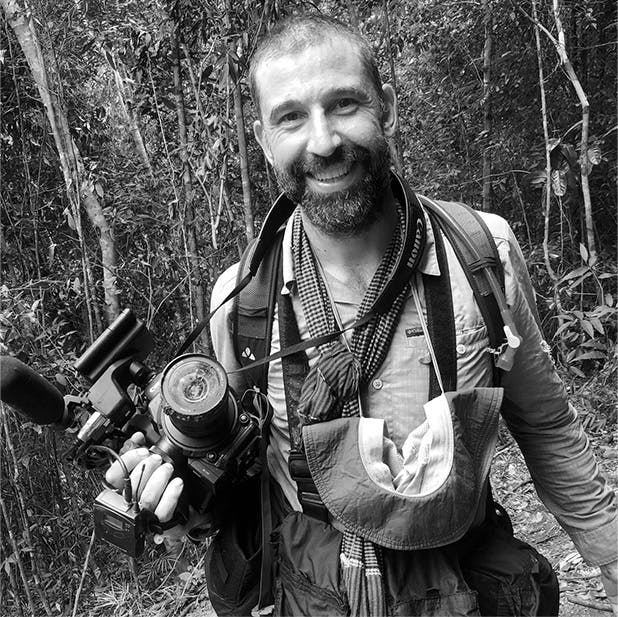

Karl Malakunas, director and producer of Delikado. Image: Delikado Facebook page

The Philippines has been listed the deadliest country in Asia for land and environmental defenders for the ninth consecutive year, based on a 2022 report by international non-profit Global Witness.

The organisation found that most of the deaths over the past decade were linked to protests against company operations, adding that “state forces are behind the majority of killings in the few cases where the identity of the perpetrators is documented.”

When Malakunas arrived in Palawan to investigate the crime, he met environmental lawyer Bobby Chan who had built a tree made of chainsaws that his group confiscated from illegal loggers. Chan is the founder of the Palawan NGO Network Incorporated (PNNI) which tracks down illegal loggers and cyanide fishers around the province’s forests and waters and apprehends them through a citizen’s arrest law, which gives power to ordinary citizens to apprehend any person committing a crime or violating any law.

Tata Balladares is one of Chan’s men who leads the group’s patrols in the forest as they wage unarmed, barefoot raids on violaters and confiscate their chainsaws, boats and dynamite.

It took years of research and back and forth between his day job as an editor at AFP, before Malakunas began actual filming for the documentary in 2017.

It was also around this time when he met Nieves Rosento, who was then mayor of world-renowned resort town El Nido. She was giving an impassioned speech at the wake of one of the town’s environmental defenders, who was shot in the head during an operation against illegal logging. Rosento is a known ally of the municipality’s environmental activists. She was also stripped of her power of control and supervision over the police by former president Rodrigo Duterte for her alleged drug ties and corruption.

“After I met these people, I started to realise that this was moving from a story simply about deforestation and illegal logging to a bigger story about the corruption that enables it,” said Malakunas.

In this interview with Eco-Business, the Australian filmmaker talks about how Filipino land defenders inspired him to complete the documentary despite its deadly repercussions, and why he thinks they will win the battle in the end.

How do you feel that your first film has been nominated for an Emmy?

I’m a bit shocked and stunned. I’m a first-time filmmaker and started making this film with no expectations. I wanted to create something that would engage audiences both in the Philippines and globally about the climate crisis.

As a journalist, there’s such a barrage of bad news that can paralyse or turn people away from taking climate action. From the very first moment I thought of the film, I wanted it to be an opportunity to do a story on deforestation, corruption and ultimately about the climate crisis.

What kind of impact do you want Delikado to have?

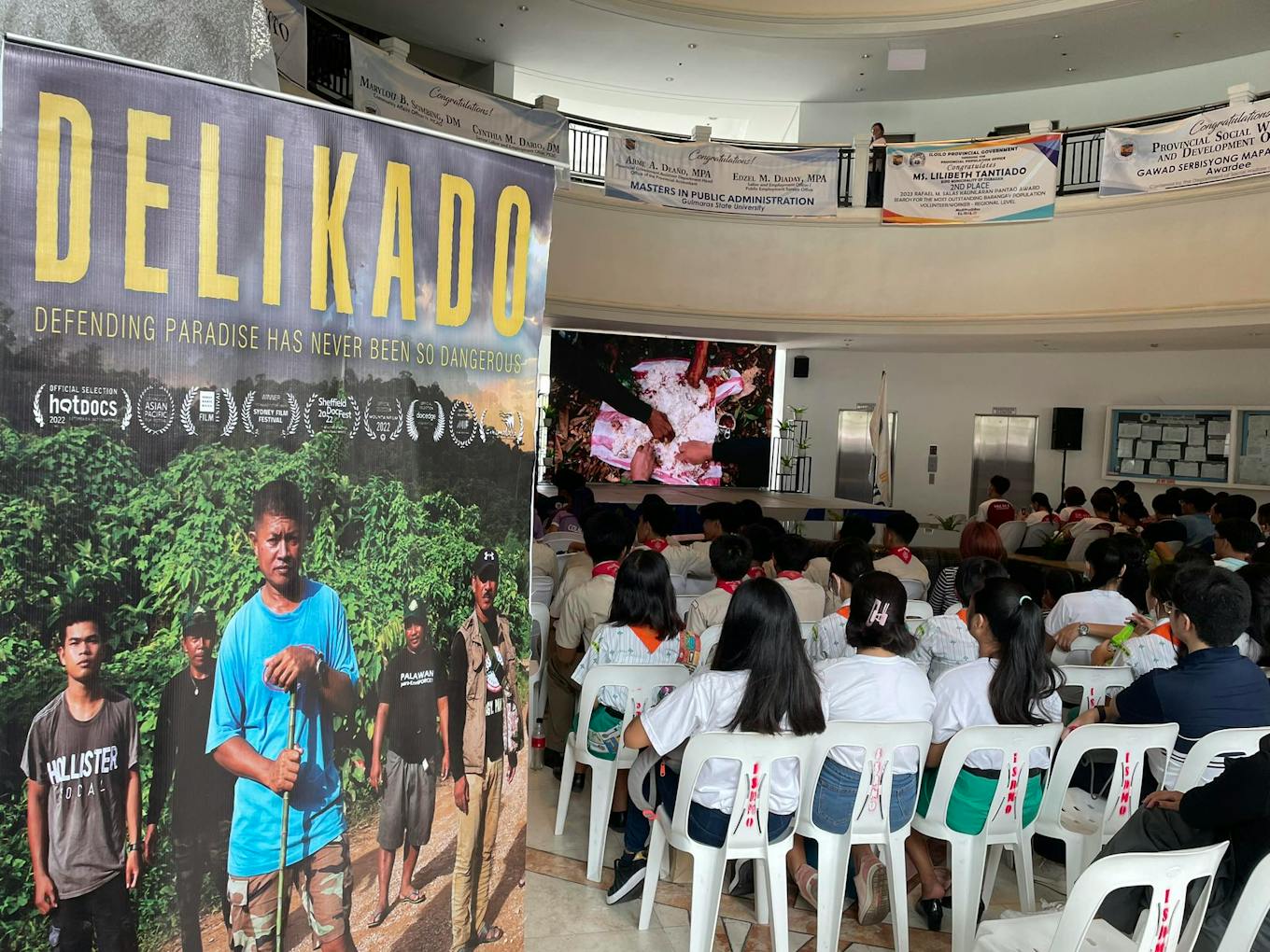

A screening of Delikado at the Iloilo Provincial Capital in 10 August. Image: Delikado Facebook page

Our main goal is to get as many screenings as far and wide as possible. It’s great that the nomination has generated more interest. It’s a recognition of the heroic, inspirational work of the land defenders of Palawan and the rest of the Philippines.

I love that the film has been able to be shown in other communities now around the country so that other land defenders who watch it will realise they are not alone. They will feel stronger and more empowered after watching the film.

We’re getting into a lot of universities where young activists are watching and it’s helping to inspire and continue this battle for the next generation.

Over the past decade, the Philippines has consistently ranked as the deadliest country in Asia for environmental defenders. Did you have any fear in making a documentary about a dangerous subject?

Karl Malakunas (far right) with cinematographer Tom Bannigan and video journalist Eli Sepe while filming Delikado in El Nido, Palawan in 2019. Image: Delikado Facebook page

I’m reporting from a position of priviledge being a foreigner. Even if I’m in Palawan for a couple of months, I have the priviledge of being able to fly back to Manila. The risks that I took are minimal and temporary compared with the risks faced by the land defenders, who have no escape.

This was a film made in my spare time, it was a second job that I worked on during the pandemic. It was such a painful, long process but every time I felt like giving up, I would think of people like Bobby, Nieves, Tata, and the land defenders who were voiceless, and that drove me to finish the film.

What are your thoughts on why environmentalism is such a deadly subject in the Philippines?

This culture of impunity in the Philippines is well known. Anyone who tries to challenge powerful interests faces incredible risks and dangers; it has been that way since before Marcos, Sr [Ferdinand Marcos, Sr, father of current president Bongbong Marcos, was president of the Philippines for nearly two decades until 1986, an era noted for unrestrained arrests, disappearances and alleged torture which provoked a revolution, which forced him and his family to flee to Hawaii, where he died in 1989.]

For instance, how could events like the Maguindanao massacre have possibly happened? It’s because powerful interests literally believe they can get away with murder.

I think it’s a long battle for journalists, environmental and rights activists to continue this effort to lower those risks. It’s an endless fight for democracy and freedom of speech, and everyone needs to play their part to fight those forces.

What sets Filipino environmental defenders apart from the rest in Asia?

There is this vibrant democracy where journalists have the space in some respects to be able to report freely; environmental activists and rights campaigners have the space to be able to protest, whereas countries like China do not have that.

But within that space come the dangers – the corruption which enables powerful interests to believe that they can threaten or kill environmental campaigners.

Do ordinary Filipinos need to be as vigilante as the characters in your film to effectively defend the environment?

They are not vigilante in a sense that they take the law into their own hands. In fact, no matter how much the law and institutions are used against them, they refuse to cut corners. They refuse to work outside the law. In fact, they continue to want to uphold law and order.

Environmental defenders are the ones who are really trying to keep the glue of the Philippine democracy together and build it: Bobby uses the citizen’s arrest law to apprehend illegal loggers, Tata has empathy for them and tries to work within the community to help them stop their trade, Nieves tries to work within the boundaries of politics even after the President names her as a narco-politician on national TV.

Nobody needs to be as radical as them but we hope the film can encourage people to take action in their own way in their communities.

Do you think Filipino land defenders will win their fight?

An audience of 1,500 gives a standing ovation to Nieves Rosento and Delikado‘s other film participants at the closing of the Cinemalaya film festival in Manila in December 2022. Image: Delikado Facebook page

The winning is in fighting and the struggle. You’re never going to have this clear finish line where you decide the winner and the loser in the environmental fight. The winning for people like Bobby, Tata, and Nieves is simply doing what they’re doing.

I look back at the People Power Revolution through decades of struggles, it’s a never ending battle to maintain freedom of speech and democracy. I’d seen the spirit from Filipinos and so I believe they can keep winning.

A screening of Delikado will be held in Manila on 12 August at the Anima Art Space in Quezon City and on 19 August at the Emily Theater in Naga City, Bicol. For more information on upcoming screenings, keep an eye on the Delikado Facebook page.

Want more Philippines ESG and sustainability news and views? Subscribe to our Eco-Business Philippines newsletter here.