It has plentiful sunshine, easy access to affordable solar technology, a progressive local government that protects its nature reserves, one of the highest recycling rates in the country, and a populace that is increasingly aware of climate change. So why has Penang, one of Malaysia’s greenest states, been so slow to transition to renewable energy?

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

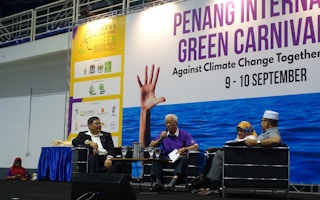

Speakers at a public forum on Sunday at the Penang Green Carnival, hosted by the state government’s Green Council, proposed that “a corruption of the mind” and a profit-first mindset are likely one of the biggest obstacles to renewable energy development in Malaysia today.

As Phee Boon Poh, chairman of Penang’s State Welfare, Caring Society and Environment Committee, put it: “Penang receives the second most sunshine in Malaysia. We have many factories with roofs that could be used for solar power generation. But unfortunately, the energy market is not open and does not attract investors in renewables.”

This is because Malaysia’s energy market is dominated by a single supplier, Tenaga Nasional Berhad (TNB), Phee said.

Phee, who is also vice-chair of the government’s Penang Green Council, responded to a question from the audience on how the state’s transition to renewable energy could be hastened. He was speaking on a panel debating how to combat climate change, which included Dato Maimunah bt Mohd Sharif, the mayor of Penang Island, and Dato Sr Haji Rozali bin Haji Mohamud, the president of the municipal council of Seberang Perai.

If the national energy market was more open and competitive, and there were more incentives to invest in renewable energy, “just imagine how quickly the uptake of solar would be in Penang,” suggested Phee.

If solar energy could be exploited to its full potential, the roofs of most buildings could be used to capture solar energy, and wind could also become a valuable part of the energy mix in the coastal state, Phee said.

“

If we eradicate corruption, we will have a better environment.

Phee Boon Poh, chairman, Penang State Welfare, Caring Society and Environment Committee

Death of the feed-in tarrif

A slow shift to renewable energy is not just an issue for Penang. Currently, only around 3 per cent of Malaysia’s energy comes from renewable sources, mostly from hydropower, with a small contribution from biomass, biogas and solar. Fossil fuels - primarily coal and natural gas - currently account for more than 90 per cent of power generated in Malaysia.

Though the country is aiming to increase the proportion of renewables it uses to 11 per cent by 2020, there are also plans for TNB to massively increase the volume of coal Malaysia uses over the same timeframe to meet the country’s growing energy demand; Malaysia’s energy needs are predicted to triple by 2050.

The pace of Malaysia’s transition to renewables took a big hit in November last year, when a feed-in tariff mechanism that enabled consumers to generate energy from solar, biogas, biomass and small hydro sources, and sell any excess power back to TB, was scrapped. It was introduced in 2011.

The net energy metering (NEM) system replaced it. This enables consumers with renewable energy capacity to make savings on their electricity bills, but they cannot sell unused electricity back to the grid.

The effect of this policy change has been to limit the appeal of renewables to environmentally conscious consumers, or those with high electricity bills.

The uptake of solar energy, the most promising form of renewable energy in Penang, has been faster among commercial and industrial customers. Businesses get tax breaks that cut the investment in renewable technology by about half, and enable savings of around 20 per cent on their energy bills.

Phee, who last month was arrested by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission because of his alleged involvement with an illegal carbon filter-processing factory, shared how he had made an appeal for tidal power to be integrated into a second bridge linking Penang Island to the Malaysian peninsula, which was opened in 2014.

Tidal energy could have powered lights for the bridge and associated administrative buildings, Phee said. “But unfortunately, one of the main reasons why this [investment in renewables] is not happening is due to vested financial interests and corruption,” he said.

Phee later qualified that by corruption, he meant a “mindset of profit gain” that ignored environmental consequences. “If we eradicate corruption, we will have a better environment,” he said.

Mindset shift needed

Though Penang’s shift to renewables is proving to be slow, the state’s chief minister Lim Guan Eng highlighted key measures that the state had taken to fight climate change and safeguard the environment.

These included giving incentives for green buildings and enforcing a policy of waste segration at source that has helped increase the recycling rate to 38 per cent, the highest in Malaysia, and well above the national recycling rate of 22 per cent. It aims to recycle 40 per cent of its waste by 2020.

The mayor of Penang Island City Council, Maimunah Mohd Sharif, who was appointed this July, the same month as the devastating floods that affected large parts of the city, added that her district was tackling climate change at a local level through measures including a bicycle sharing scheme, cycling lane infrastructure that spans the island, the installation of LED street lights and the introduction of a car-free day every Sunday.

Municipal council president Haji Rozali bin Haji Mohamud also noted during Sunday’s panel discussion that the region of Seberang Perai was investing in a tree planting scheme, solar farms and waste reduction programmes that aim to halve per capita carbon emissions by 2022.

Phee said that while he was proud of what the state had achieved to become “cleaner, greener, safer, healthier and happier” - Penang’s slogan - there is much to be done to make a state that was severely hit by flooding in July more climate resilient.

For instance, all new high-density buildings should be built with biodigesters to generate biogas from food waste, not only to help power the buildings themselves but to provide cheap electricity for the local council to power lighting in common areas, he said.

Biogas should also be harvested from the sewage systems of the state’s highly polluting chicken and pig farms, said Phee, adding that for this to happen would require a change in the laws that prohibit the re-use of animal waste.

In conclusion, Phee said: “The heavy rain and flooding in Penang also affected our neighbours, and shows us that we are not alone in facing climate change. We must not be selfish. The question is not is climate change is real, it’s how we respond to it. It’s happening everywhere, and everyone must play a role.”