It’s some time in the not too distant future. The American mid-west has turned into a dust bowl. Birds are dropping out of the sky. Cities are encapsulated in domes so that people can breathe clean, if recycled, air.

Billions of refugees, victims of drought and famine, are on the move. The streets are full of violent gangs and human traffickers. Pandemics are breaking out.

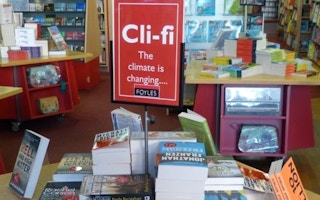

Welcome to a new literary genre – climate fiction, or cli-fi.

Some of it might be sensational, some of it not exactly great literature, and some downright depressing, but there’s little doubting cli-fi’s growing popularity.

Cli-fi – along with its elder brother sci-fi – is now considered part of modern literature’s classification system. Though some titles make only a passing reference to climate change, while others are more concerned with murder, mayhem and sex than with global warming, others are more thoughtful, science-based works.

Well-established novelists have used climate change as a backdrop in their books.

The prize-winning writer, Ian McEwan, in his 2010 novel Solar, describes the world of physicist Michael Beard – a man of apparently insatiable sexual and culinary appetite – and his invention of a system for solving the global energy problem.

Margaret Atwood, the Canadian poet and novelist, has often used environmental catastrophe as a theme in her work: her trilogy MaddAddam graphically describes global floods and battles with criminals. Ultimately civilisation – and the environment – is rebuilt.

“There’s a new term, cli-fi, that’s being used to describe books in which an altered climate is part of the plot”, Atwood writes in The Huffington Post.

“Dystopic novels used to concentrate only on hideous political regimes, as in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

“Now, however, they’re more likely to take place in a challenging landscape that no longer resembles the hospitable planet we’ve taken for granted.

“Whether fictional or factual, the coming decades don’t sound like a picnic. It’s a scary scenario, and we’re largely unprepared.”

Academic engagement

The emerging cli-fi genre has given birth to new courses at universities: academics say cli-fi helps people, particularly the young, engage more in science – and in the dangers posed by climate change

Sarah Holding is the author of several cli-fi books aimed mainly at a younger audience. In a review of cli-fi books for children in The Guardian newspaper, Holding says the new genre helps young readers value their environment.

“…These books are posing new questions about what it means not just to survive but to be human. Don’t be put off by the preponderance of floodwater or the scarcity of basic resources – what you’ve got here are fast-paced, intrepid adventures into the unknown…”

Dr. Renata Tyszczuk of the University of Sheffield in the UK is running a project called Culture and Climate Change, which aims to involve the wider artistic community in the issue.

Tyszczuk says cli-fi is one area where culture has responded to climate change and includes some great work – but it’s not enough.

“Climate change is viewed by universities and many others as a science and technology ‘problem’ which needs to be solved.

Doubters

“The arts are in a position to help put this difficult new knowledge into a much wider context and in so doing encourage more thoughtful and purposeful responses.”

Not everyone is convinced cli-fi is a good thing. There is concern that critical issues relating to the planet’s future are being trivialised in a series of sensational novels.

George Marshall is founder of the UK-based Climate Outreach organisation and author of a book on communicating climate change.

Writing in the New York Times, Marshall says cli fi will do little to help the battle against climate change.

“I predict that ‘cli-fi’ will reinforce existing views rather than shift them. The unconvinced will see these stories as proof that this issue is a fiction, exaggerated for dramatic effect.

“The already convinced will be engaged, but overblown apocalyptic storylines may distance them from the issue of climate change or even objectify the problem.”