“If this coal plant pushes through, our sky will turn grey,” said Crisanto Palabay above the shouting of the 200-strong crowd behind him.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Wearing a white t-shirt, khaki trousers and no shoes, the spry 63-year old farm manager was standing behind a banner that read “Protect La Union. No to coal in Luna!” at the head of group of demonstrators from The Coalition to Save the Beauty of La Union, a community organisation protesting the development of two coal-fired power plants in the northern Philippines province.

On 13 July, Palabay led a march, barefoot, through the streets of provincial capital San Fernando to protest the two 670-megawatt (MW) coal plants to be built in Luna, a town 34 kilometres away. Construction is scheduled to start next month and the plants are expected to begin operations in the first quarter of 2022.

“We want to protect our seas, our people, our livelihood. Besides polluting the environment, these coal plants will affect our health,” he told Eco-Business during the march.

The community-led coalition wants the $1.5 billion project scrapped, saying emissions and waste from the plants will not only harm Luna residents but also communities within a 50-kilometre radius and the province’s last intact rainforest, Mt. Kangisitan. The town’s residents rely on tourism, stone picking, and fishing for their livelihoods, which they fear will be impacted by pollution and the frequent transport of imported coal to the plant site.

Aerial map of the proposed site of the Luna coal-fired power plants in Carisquis and Nalvo Sur, Luna, La Union, Philippines. Image: Environmental Justice Atlas, via Creative Commons

Non-governmental organisation Philippine Movement for Climate Justice ‘s (PMCJ) national coordinator, Ian Rivera, said the people need only look at other communities where coal plants exist, such as in Limay, Bataan and in Balingasag, Misamis Oriental to understand the threat coal-fired plants pose. Fish caught in these areas have tested positive for heavy metal contamination.

“The impact of coal is a public issue and the communities affected by the operation of coal plants are now standing up to call for end to this dirty, costly, deadly fossil fuel,” said Rivera, whose organisation is supporting the resistance against the Luna coal plants alongside Greenpeace. PMCJ is also supporting the protest against coal in Atimonan, Quezon led by a local parish.

Representatives of developer Global Luzon Energy Development Corporation (GLEDC), a subsidiary of Global Business Power Corporation (GBP), did not confirm if the company has secured an environmental compliance certificate (ECC). Any development that poses potential environmental risks must obtain an ECC before construction, according to federal law.

Volunteers join a beach clean-up in San Juan, La Union. The town attracts surfing enthusiasts, but its beaches are threatened by the proposed coal plants in Luna. Image: Grace Duran-Cabus/Greenpeace

“

If you put the solar panels that China installs at home in a month in the Philippines, you would not have to worry about electricity supply.

Lauri Myllyvirta, air pollution expert, Greenpeace East Asia

Chinese hypocrisy

The proposed coal plants in Luna will allegedly use technology which burns less coal per MW of electricity, leading to fewer emissions, but Beijing-based Greenpeace air pollution expert Lauri Myllyvirta said that “clean coal” is no more than a “marketing ploy”.

“I would not call the lowest emissions coal plants clean, because they are still more polluting than any other power generation technology,” he told Eco-Business.

Yet the Philippines’ energy department has fallen for it. On May 22, energy secretary Alfonso Cusi signed a Memorandum of Understanding with China Energy Development Corporation for three 1,500-MW coal-fired power plants featuring the same technology to be built in Luzon and Cebu starting in 2020.

Despite having taken drastic measures—including shutting down coal plants in Beijing and setting stringent emission controls for existing plants—to stamp out pollution at home, China has continued to build new coal-fired plants in countries where emission limits remain lax.

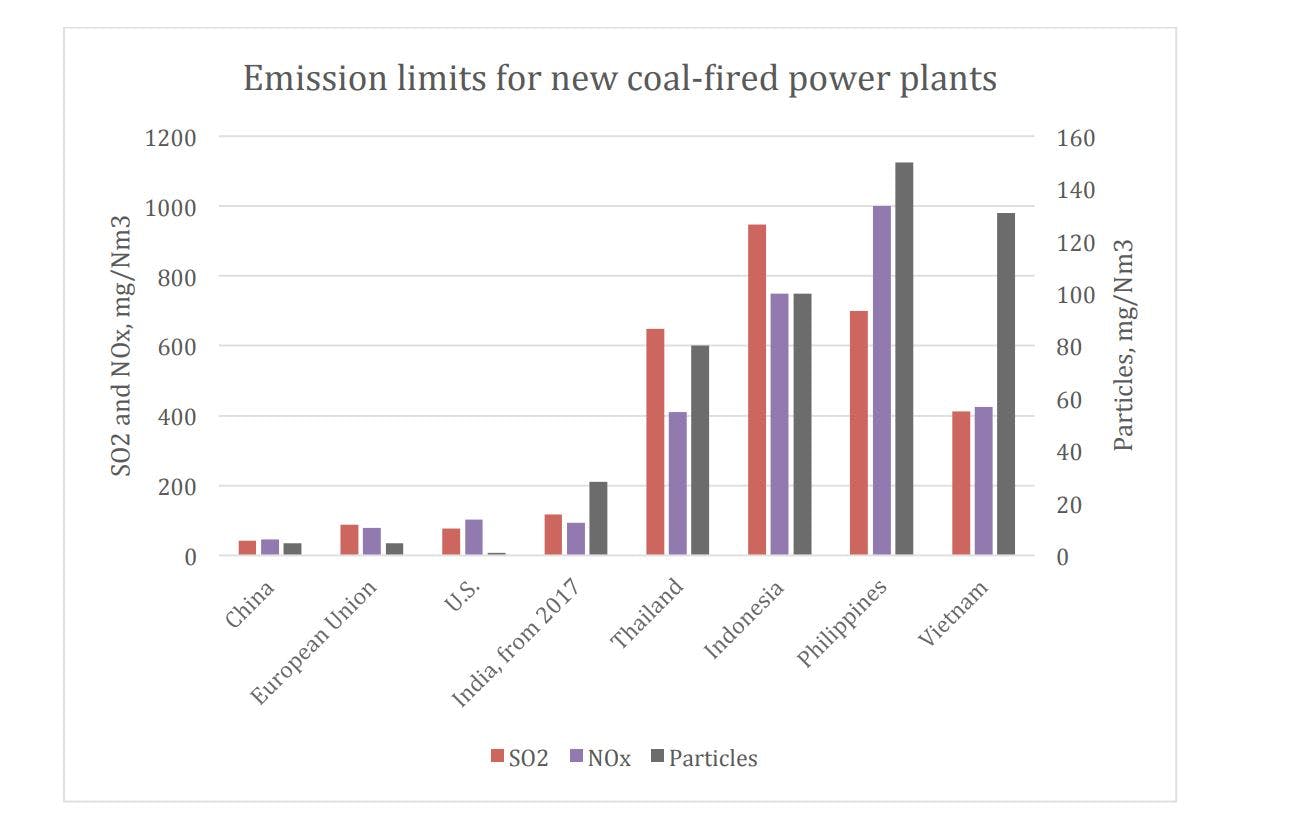

For instance, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand have relatively generous emission limits for new coal-fired power plants compared to India, the United States and even China.

Comparison of emission limits for new coal-fired power plants in different countries. Source: Greenpeace

This allows companies from Japan, China, and South Korea to build far more polluting power plants than they would at home, Myllyvirta pointed out.

At the same time, the adoption of renewable energy has been slow. Philippine Senator Loren Legarda pointed out at a symposium in Quezon City last week that the country’s adoption of renewables has grown by a “paltry 3 per cent” in the decade after the introduction of the Renewable Energy Law, which aimed to spur investments in renewable energy.

Installed capacity of renewable energy increased by an average of 157 MW per year. In total, renewable energy capacity grew from 5,226 MW in 2005 to 6,958MW to 2016.

“These figures present one glaring fact—we have failed miserably in meeting our goal of doubling the installed capacity of renewable energy, ” Legarda said, citing the goal of increasing renewable energy generation from 4,450 megawatts (MW) in 2002 to 9,418 MW by 2013.

Claims that renewable energy is an expensive alternative for power generation were wrong and were “the most convenient excuse against the status quo,” she said.

Thanks to a decrease in the cost of renewable energy technology, onshore wind power now costs $0.06 per kilowatt hour (kWh) of electricity and solar energy between $0.05 to $0.10 per kWh, while electricity from fossil fuels typically falls in the range of $0.05 to $0.17 per kWh.

Elpidio dela Cruz, 62, stands in a graveyard adjacent to a 140 megawatt coal-fired power plant in Barangay Lamao in Limay, Bataan, northern Philippines, January 18, 2018. Thomson Reuters Foundation/Alanah Torralba

Instead of partnering with China on coal projects, the Philippines should tap the country’s renewable energy expertise for clean energy, campaigners said. China is the world’s largest producer of solar and wind energy technologies.

“If you put the same number of solar panels that China installs at home in a month in the Philippines, you would not have to worry about electricity supply,” Myllyvirta said.