Burning season is in full swing in Indonesia.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The annual haze caused by slash-and-burn forestry hasn’t been as intense as in previous years, and neighbours Singapore and Malaysia haven’t complained of smoke and the smell of burning wood drifting across their borders.

But a state of emergency was declared in Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, West Kalimantan and South Kalimantan in July, and fires continue to break out, even as the rainy season approaches.

According to satellite forest monitor Global Forest Watch (GFW) there were 9,072 fire alerts in Indonesia between 14 and 21 September, the peak month of the dry season.

That the fires haven’t reached the Dantean ferocity of two years ago when Southeast Asia experienced its worse bout of haze pollution on record — and burning peatlands produced more carbon dioxide than the European Union emits in a year — is particularly good news for one company.

Asia Pulp & Paper (APP), Indonesia’s largest pulp and paper firm, was heavily implicated in the devastating forest fires of 2015. The firm was blamed for about a third of the fires that enshrouded Southeast Asia that year, and has since lost millions in revenue after retailers in Singapore removed the company’s products from their shelves.

Numerous fire alerts have been identified on APP’s concessions again this year—on 21 September, 66 fire alerts were identified on the concessions of APP fibre supplier PT Finnantara Intiga—but the company tells Eco-Business that none of them turned out to be real fires; they were hotspots, mostly likely caused by smouldering piles of compost.

APP’s effectiveness at controling the fires that have blighted much of the region for almost half a century has dramatically improved, thanks to the millions it has spent on fire suppression and prevention, and partly due to favourable weather—this year’s dry season has been a lot wetter than usual.

But a new pulp mill that APP quietly put into operation nine months ago, PT Ogan Komering Ilir (OKI) in South Sumatra, has caused concern among environmentalists who say the massive facility will inevitably lead to forest fires and haze in the region for decades to come.

Rumour mill

A coalition of 12 non-government organisations that includes World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), Wetlands International, Rainforest Action Network, Hutan Kita Institute, Forest Peoples Program and Woods & Wayside International, claims in a report, titled Will Asia Pulp & Paper default on its ‘zero deforestation’ commitment?, that the mill does not have sufficient wood supply from its plantations to sustain itself.

This, they argue in the study, will mean an environmental and social disaster in the making for Indonesia and the region. Once the supply of plantation trees runs out, they predict that more deforestation, greenhouse gas-spewing peatland fires and land disputes will follow at the hands of a company that has, according to a study by Eyes on the Forest in 2011, razed an area of natural forest equivalent to 28 Singapores over the last few decades.

The company in February 2013 launched a Forest Conservation Policy, which was a promise to stop clearing natural forests, developing carbon-rich peatland and seek free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) from local communities before developing on their land.

These are all practices that APP has been accused in the process of building a multi-billion dollar business over close to half a century.

The new mill—the third that APP has built in Sumatra, and its largest—will make it impossible for the company to fulfil its FCP commitments, environmentalists claim.

Ramping up capacity

Log trucks each carrying 33 tonnes of fiber trundle in around the clock. Image: Eco-Business

At the mill’s land entry point for timber, an average of 524 trucks a day, each loaded with around 33 tonnes of wood, trundle in around the clock.

At the river unloading point, also operational 24 hours a day, seven days a week, a row of 12 docking points are open for a floatila of titanic barges, each carrying up to 3,500 tonnes of wood that will eventually be processed into pulp and paper products, which are sold in packaging that reads ‘Made from 100 per cent plantation forests’.

At the start of the year, the mill’s average production capacity was 3,000 tonnes of pulp per day, using only one of two fiber lines. But in mid-May, the second fiber line was fired up, increasing production to 5,000 tonnes of pulp a day.

From June to December this year, the company has ramped up production to 5,800 tonnes per day. This is, the company tells Eco-Business, 85 per cent of the mill’s licensed production capacity of 2.8 million tonnes a year.

However, a document recently obtained by Eco-Business suggests that the mill will be able to churn through a lot more timber than the company has been letting on.

OKI has, in fact, the capacity—and government approval, through a licence issued by Indonesia’s Capital Investment Coordination Agency (BKPM)—to produce 3.25 million tonnes of pulp a year.

At this capacity, say environmentalists, there is no way that the company will be able to feed the mill using only trees harvested from its plantations, placing the natural forests that are home to indigenous communities and endangered species such as orangutans, tigers and elephants under even more pressure.

By June 2018, APP plans to open a new tissue paper facility that will further increase the mill’s appetite for wood.

Also to come is a sea port that will make it easier for APP to ship its wares overseas; 85 per cent of the mill’s products are destined for foreign markets, mainly to India and China.

The wood crunch

APP makes two arguments to quash concerns about OKI mill’s wood supply. The first is that the company will ship in timber from outside Sumatra to feed the mill if supply is running short, either from Kalimantan, where the company has other plantations, or from overseas markets such as Australia or Vietnam.

But critics suspect this will prove to be too costly. The cost of wood - which makes up 60 per cent of OKI mill’s operating costs - could prove to be “considerably more expensive” if it is shipped in from the nearest source outside of Sumatra - Kalimantan, according to the coalition of NGOs behind the wood supply report.

Gadang Hartawan walks past OKI mill’s vast log yard.

During a recent visit to OKI, the mill’s vice director, Gadang Hartawan, told Eco-Business this is not true, as its suppliers will bear the cost of wood delivery, and APP will pay for material only after it has been weighed.

The other argument, made repeatedly by APP and recently at Temasek’s Ecosperity conference in Singapore by Thomas Lembong, the chair of BKPM, is that the mill does not need to run at full capacity. Tuning down production also allows the machinery to be properly maintained, the company says.

APP says that it will be flexible about the capacity of the mill - and therefore the amount of wood needed to feed it. But Bas Tinhout, technical officer, climate-smart land use for green group Wetlands International, suggests that the introduction of the tissue facility in a year’s time will make this flexibility less realistic.

“APP committed to adapt the pulp mill capacity according to a sustainable plantation fiber supply. However, with cascading demands from a tissue facility depending on the pulp supply this promise will be harder to keep,” he says.

The biggest wood supply headache for APP comes from the fact that most of its plantations - 70 per cent that supply OKI mill currently - are grown on peatland, Tinhout points out.

Peat, a soggy soil, is too wet to support acacia, APP’s main crop for producing timber. It must therefore be drained first, a problematic practice because dry peat is extremely flammable.

Tinhout is not convinced that APP can meet it current fiber demands, given that OKI mill is slated to be running at 85 per cent capacity by the end of the year. He says that the fires of 2015, the worst of which occurred in the area around OKI, have squeezed an already stretched wood supply.

What exacerbates the situation is that 37 per cent of APP’s plantations in South Sumatra were consumed by fire in 2015, and cannot be replanted. And with 60 per cent of APP’s concessions on peat, and a government ban in place on peatland exploitation, the company’s expansion plans are limited.

Tinhout points out that APP’s peat-based plantations are not only at high risk from fire, but also threaten the environment near them. The drainage canals that run through the plantations leach water from neighbouring forests and local community land, while the roads leading to the plantations give outsiders easy access to fire-prone areas.

He says: “APP has a track record that shows its inability to prevent major fires within their planted and unplanted plantation areas.”

Sceptics of APP’s claims that it will tune down production of the mill if necessary also point out that the company is under intense financial pressure to run the facility at full capacity - and keep it there.

Most of the US$2.6 billion mill investment comes from a loan provided by China Development Bank and other funders, and the debt is repayable on a 12-year schedule. APP’s ability to meet its financial obligations will depend on the profitability of the mill.

“

Our sense is that APP are serious. What matters is that they do what they say.

Richard Donovan, senior vice president, forestry, Rainforest Alliance

Conflicting research?

In addition to its financial obligations to keep the mill running, another reason experts doubt that APP will only use plantation wood is the questionability of the research which served as the basis for it to be built.

A study by research groups The Forest Trust and Ata Marie in 2014, commissioned by APP, found that the company had sufficient plantation wood to feed the mill. But critics point out that the research was valid only until 2020.

TFT programme manager Arief Perkasa tells Eco-Business that “We could have projected beyond 2020, but it might not have been accurate.”

The study, which took two months to complete and involved visiting 4,400 plots of land, was updated mid-last year after the forest fires of 2015. It drew the same conclusion: that with the improvements the company was making to increase productivity, APP would be able to meet its fibre targets and even produce a surplus within a decade.

The original study identified a gap in fiber supply in 2020, but TFT’s executive director Scott Poynton said in 2014 that it could be “easily filled” if the company increased the productivity of its plantations.

An evaluation of TFT and Ata Marie’s findings by Rainforest Alliance in 2015 confirmed that APP had sufficient fiber supply. But questions remain about the exhaustiveness of the report.

RA did not do its own research, but relied on APP data and a series of “confidential” interviews with company executives and suppliers that were not made public, according to a source familiar with the process.

A report launched by a coalition of 12 international and local NGOs including Woods & Wayside International, WWF and HaKi in April 2016 contradict both The Forest Trust and Rainforest Alliance’s findings.

The study found that the company was well short on wood to feed the mill—even before the destructive forest fires of 2015.

While the underlying assumptions made in TFT and RA’s research were not made public due to commercial sensitivities, the NGOs’ study revealed the assumptions and calculations used to reach its conclusion.

These included wood loss rates and a range of tree growth rates for APP’s plantations. Even the most optimistic scenario indicated that the mill would face a serious fiber crunch.

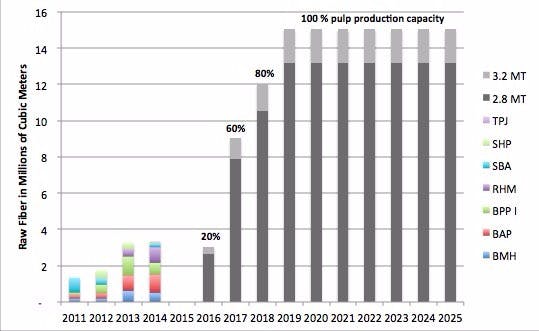

Comparison of plantation grown pulpwood production by APP concessions (supplying companies represented by acronyms) in South Sumatra from 2011-2011, and projected annual wood fiber demand by the OKI mill under pulp capacity scenarios of 2.8m and 3.2m tons/year from 2016-2025. Source: Adapted from 2016 report by 12 Indonesian and international NGOs

Some NGOs suspect that TFT and RA’s research was fudged to satisfy sceptical stakeholders. Richard Donovan, who has led RA’s forestry programmes since 1992, tells Eco-Business that he can understand why cynicism surrounds a company with such a troubled history, but says that these suspicions are “just a lot of conjecture.”

“It doesn’t tally with what is really happening on the ground,” he says, pointing to the work that APP has been doing to keep faith with its FCP commitments.

One of APP’s key strategic ambitions is to re-engage with Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a forest products certification body that broke off ties with the company a decade ago because of the company had been found to have defaulted on a pledge to identify and monitor high conservation value forests.

The process of re-engagement has begun, and Donovan suggests that APP would not want to jeapardise a potential certification deal that would help the company sell more products by carrying the FSC logo.

“Our sense is that APP are serious [about FCP commitments]. What matters is that they do what they say,” says Donovan, whose organisation backed out of a project to help APP preserve high conservation value areas in its concessions in 2006 after it emerged that the company had been clearing the areas it had claimed it would protect.

“It’s quite clear that if you saw APP begin to start clearing natural forest to make up the [fiber] supply gap, frankly speaking, it would halt any process of reassociation with FSC. I don’t think that it matters to all customers, but it matters to key and visible stakeholders.”

Rainforest Alliance recently signed another large research contract with APP.

Not everyone is convinced of the role of the group, or TFT, as an agent of environmental stewardship, however.

Patrick Anderson, a former Greenpeace campaigner now with indigenous community rights group Forest Peoples Programme, comments: “The Forest Trust and Rainforest Alliance - they sometimes present themselves as NGOs, but they’re consultancies hired by companies like APP to make their activities somewhat less damaging.”

A shield for deforestation?

APP’s most cynical critics believe that not only has the company used the growth and yield studies to provide safe passage for the mill, but also used its former enemies as a deflector shield for criticism.

The firm’s longest-running adversary turned ally is Greenpeace, the NGO that muscled APP to the negotiating table in 2013 after two decades of locking horns.

The result was APP’s widely praised Forest Conservation Policy. Some NGOs sources snipe that the company has used the FCP as a diversion tactic to enable the mill to be built free from scrutiny; and that Greenpeace’s lack of public criticism also provides air cover for APP.

Critics suspect that key architects of the agreement on Greenpeace’s side became too closely embedded with APP, which led to the eventual sacking of one senior campaigner who had developed strong ties with the company.

Maitar: “We should give space to APP to fulfill their commitments.”

Another former Greenpeace Indonesia staffer, Bustar Maitar, who led the campaign against APP for more than a year before successfully bringing the company to the negotiating table, and who received death threats from APP supporters during that time, now runs an environmental consultancy, EcoNusantara. The firm advises APP.

Maitar, who says he receives no compensation from the firm, believes that APP will not default on its commitments. He points out that the plan for OKI mill was a “business calculation” that was factored into the company’s FCP pledge.

Maitar says that if OKI mill’s wood supply runs low, APP will simply lower the capacity of its mills or use timber supply from overseas rather than return to plundering forests.

He adds that an often overlooked critical factor is the embarrassment that failing on its commitments would cause APP.

“When the commitment was announced, the owner of APP, Franky Widjaja, stood in front of an audience and said that he wanted to make this happen. I don’t think APP wants to lose credibility - especially this family.”

In response to the assertion that Greenpeace had helped pave the way for APP to build a forest-threatening mill, Maitar is sanguine.

“If the NGOs are still suspicious, and don’t trust APP, that’s fine—they’re doing their job. But we should give space to APP to fulfill their commitments,” he says, adding that APP will not want to jeapordise the process of reassociating with certification body Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).

“I do understand that some people want to see them [APP] fail. But I don’t want to see that. If they do, it will set a worrying precedent for the industry. Rather than bracing for failure, we should be thinking together how to ensure they stick to their commitments,” he says.

Commenting on behalf of Greenpeace is Andy Tait, a well respected activist who has worked for the NGO for 17 years. He says that the group has campaigned against APP around the world for many years, and since the company stopped cutting down rainforests, Greenpeace has “pushed” it to deliver on its zero deforestation commitments and to manage peatland more responsibly.

“The company still has a lot of work to do to deliver on these commitments,” says Tait.

“APP’s decision to stick with plans to build a major new mill have rightly led to doubts being raised about how it can both feed the capacity of this mill and stick to its sustainability commitments.”

“Greenpeace and other NGOs will obviously continue to hold APP and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL), the other major pulp company in Indonesia, to account to implement sustainability commitments and to compensate for highly irresponsible past practices.”

A change in chief sustainability officers

Greenbury: It would be “commercial suicide” for APP to renege on its FCP commitments

Aida Greenbury, APP’s chief sustainability officer, who abruptly left the company in May, has also caused some critics to wonder what would become of the commitments that the outspoken Indonesian had fought for over a 13-year career.

One of Greenbury’s biggest achievement was negotiating a US$10 million a year pledge to restore 1 million hectares of Indonesian peatland, which could end up costing APP in the region of US$1 billion to implement, according to a source close to the company.

Greenbury’s replacement as head of APP’s sustainability function, and also the head of its Singapore operations, is Bernard Tan, a former Singapore army general and head of the intelligence services.

With Greenbury gone, will APP now start to unravel its forest protection commitments?

Greenbury, who has set up an eponymously named consultancy and has recently joined FSC and Mongabay’s Board of Advisors, tells Eco-Business that it would be “commercial suicide” for APP to renege on it pledges. APP has lost millions in lost contracts because of its destructive forestry practices, and would lose millions more if news broke that the company had gone back on its promises.

APP’s headquarters in Pasir Panjang, Singapore. Image: Eco-Business

APP’s progress report card

As things stand, APP says that it is on track with the improvements it is making to its operations, which will ensure that its forest conservation commitments remain intact.

They are: increasing yield by better control of disease and pests, trialling strains that can thrive on peat soil, and reducing wood waste.

Just a few years ago, the company was losing around 12 per cent of the wood that it was felling. Trees were being cut down using excavators instead of chain saws, which are much better at harvesting the tree closer to its root. According to the company, wood loss has been reduced to 9 per cent.

Though its record of fires in its concessions is alarming, the company has put serious money behind measures to supress and prevent them. The company has invested around US$20 million in tackling fire, from thermal image cameras mounted to super puma helicopters, to rewarding smallholder farmers that refrain from burning land with financial incentives.

APP’s promise to restore 1 million ha of rainforests is still very much in its infancy, with only a few thousand hectares in its concessions in the process of being restored. But achieving such a big target is feasible for a company with a land bank of 2.6 million hectares—if it focuses on land that is under its full control, says Tinhout of Wetlands International.

He points to APP’s Tripupa plantation in South Sumatra, which was retired and rewetted before the 2015 fires. It was the only concession in the province that stayed fire-free.

Community conflict

APP also faces another challenge in addressing the rights of local communities.

Through Jokowi’s ambitious but snail-paced agrarian reform programme, Indonesia has only just started to recognise the land rights of local communities, who for generations have lived on the land without legal title deeds. This grey area has enabled big agribusiness firms like APP to move in after securing industrial forestry permits from the government, and then push people off their land without Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC).

Fitri: “APP didn’t follow their own policy” on community conflict

Aidil Fitri, director of Haki, has been rallying against OKI mill since the plans to build it started to emerge in 2010. He says that communities living in the area around the mill were not properly consulted before it was built.

“APP didn’t follow their own procedures and policy [on FPIC],” Fitri told Eco-Business during a recent visit to Palembang. Villagers living in the OKI regency had no idea what form the construction would take, and now complain of noise, smell and water pollution.

More troubling, says Fitri, are the fiber supplier options APP is considering. One is PT Bangun Rimba Sejahtera (BRS), which according to a report from Haki and other NGOs has used intimidation tactics during consultations with community groups, bringing in the police and army to officiate proceedings.

If APP selects BRS as a supplier - a decision the company says is under review - 100,000 people living in 40 villages in the province of Bangka Belitung in South Sumatra will be affected by the transformation of a landscape where pepper, rubber, bamboo, oil palm and the lucrative Kayu Pelawan mushroom are grown, into monoculture for the timber industry, according to report. The concession, it reads, “threatens the economic foundation of the society.”

Fitri questions APP’s claim that it will look overseas for wood if its own fiber supply runs out. “They will push the government for more land in Sumatra. And that will badly affect the people and the environment in the long run.”

APP is currently working through 400 cases of conflict with local communities over land, and says that it has resolved - or is in the process of dealing with 40 per cent of them.

One successful example of conflict resolution came in April, in the district of OKI. APP supplier PT Bumi Mekar Hijau (BMH) agreed to share a 10,000-ha plot of land with the people of Riding Village.

Some of the land, for which BMH has a forestry licence, will be used for acacia plantations to feed OKI mill. But the land will be intercropped with green spaces for ox feed, settlements and other crops.

The Riding case is a minority in APP’s dealings with local communities, says Patrick Anderson, policy advisor, Forest Peoples Programme, who points to 23-year-old community activist Indra Pelani, who was beaten to death by security guards working for an APP-owned firm in 2015, as a painfully recent memory. But he says that at least APP is now committed to negotiate with communities before moving in on their lands.

As for OKI mill, local communities were unaware that thousands of new people would be moving into the area, and the landscape irrevocably changed, and livelihoods affected as a result, Anderson says.

“

The only responsible way forward is for APP to drastically reduce their plantations on drained peat.

Brian Orland, senior associate, Woods & Wayside International

For peat’s sake

Looking to the future, the biggest problem facing APP is peat, large tracts of which have been drained and developed into plantations.

If the peat subsides, as it is prone to after it has been drained, as much as 60 per cent of APP’s peat-based land could eventually be rendered unfarmable, as flooding and diseases such as root rot and canker ravage yields.

The company is trialling species that thrive on peat - known as paludiculture. But these species are some way off from being commercially viable.

Producing a fiber from paludiculture at a cost that is competitive is one problem. Another is that some vegetation must remain in place when the crop is harvested to ensure that the sun does not dry out the peat. This raises costs and lowers productivity.

While APP may be serious about developing a peat-friendly crop, some suspect that it is using its research efforts to buy more time for its plantations on drained peat.

“The only responsible way forward is for them to drastically reduce their plantations on drained peat,” says Brian Orland, senior associate, Woods & Wayside International. “Paludiculture for pulpwood production does not seem like a commercially viable alternative in the short term.”

This is a challenge that is not APP’s alone. APRIL, Indonesia’s second largest pulp and paper company, is around a third the size of APP, but grows an even larger proportion of its crops on peat.

The riskiness of peat-based plantations came to prominence for APRIL this month, when the operations plans of subsidiary PR RAPP were declared legally invalid after the company was found to have ignored new regulations on peat management, which prohibit tinkering with water levels or developing new plantations on the carbon-rich soil.

The news was a reminder of the squeeze agribusiness firms operating in the area now find themselves under.

Now, the race is on for APP, APRIL and others to find crops that can grow well on peat, or secure land on less vulnerable soil.

The fate of Indonesia’s pulp and paper firms—and that of the country’s remaining rainforests and the communities that depend on them—depends on how this race plays out.

Check out our accompanying photo essay: In pictures: APP’s mega mill