It has barely been two months since Korean-Indonesian conglomerate Korindo bowed to demands from environmental activists and announced a moratorium on forest clearing in its palm oil concessions, but campaigners claim that the company has already broken that promise.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

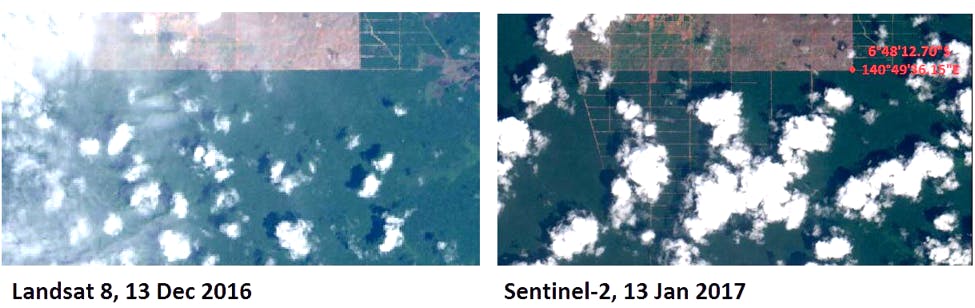

Through satellite images obtained on 13 January 2017—about a month after Korindo’s moratorium announcement—United States based non-governmental organisation Mighty found that Korindo was preparing to clear about 1,400 hectares of forest in an area that it had promised to stop clearing until the land had undergone proper audits to assess its conservation value.

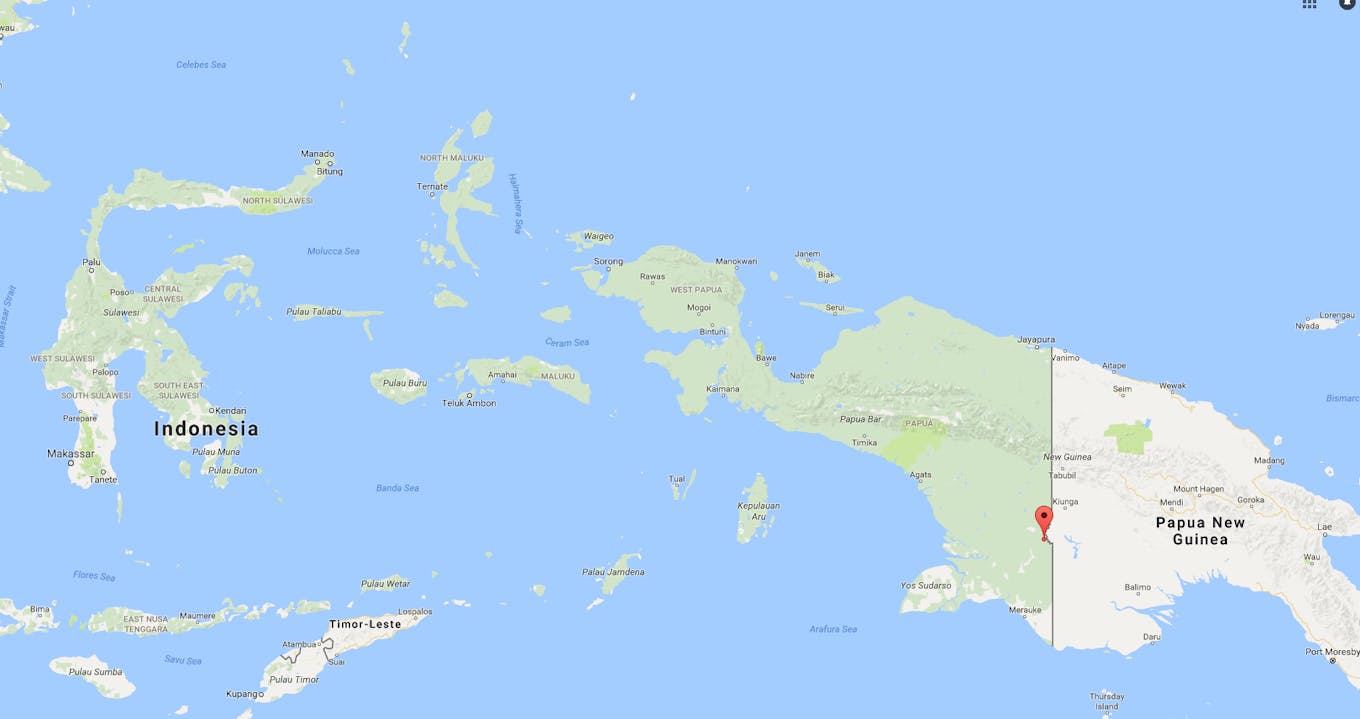

The land patch is located in a concession controlled by Korindo subsidiary PT Papua Agro Lestari (PT PAL), close to the border between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

The images show a grid of cleared vegetation intersecting the forest landscape, which Mighty says is a process called “stacking”, or carving out plantation blocks. This is the final step of land development before forest clearing.

The lines were not visible in satellite images of the same tract of land taken on 13 December 2016.

Deborah Lapidus, campaign director, Mighty, said that “when we met with Korindo in Jakarta three weeks ago, they assured that they were adhering to their moratorium.”

Given that satellite images show Korindo bulldozers getting ready to clear large tracts of forest, “we are very disappointed at Korindo’s duplicity, and urge them to immediately halt all further development,” added Lapidus.

Satellite image comparing a plot of land within PT Papua Agro Lestari’s concessions. The image on the right shows plantation blocks being carved into the land, but there is no evidence that Korindo has conducted a proper sustainability assessment before proceeding with development. Image: Mighty

Location map of Korindo’s PT PAL concession, where the satellite images were taken.

The correct process for going ahead with planned developments is to engage auditors to assess the land for high conservation value (HCV) and high carbon stock (HCS). These auditors must be licensed by, and the assessments approved by, industry bodies such as the the High Carbon Stock (HCS) Quality Review Panel and the HCV Resource Network’s Assessor Licensing Scheme.

However, while Korindo claims to have completed these assessments using licensed HCS and HCV assessors, the HCV Resource network has said that it has not received any evaluations to evaluate. The assessments cannot be considered valid.

Assessments for PT PAL are also not listed as completed or ongoing on the HCS Approach or HCV Resource Network website.

Korindo replied to Mighty on Thursday to say that there was a moratorium on forest clearing in PT PAL, and it finalised the “self-assessment” results of HCV and HCS assessments during that time. The assessments are available on the PT PAL website.

However, the peer-review for the assessments has not been completed yet. “Since the HCV (and) HCS is a voluntary enforcement rather than an obligation of the Indonesian government, the moratorium was lifted after obtaining the results of the survey,” the company told Mighty.

Lapidus said that Korindo’s response indicated that the company “basically deceived” Mighty during their meeting, when Korindo expressed uncertainty about being able to maintain the moratorium while the independent panels were evaluating their assessments. In reality, the moratorium had already been lifted, said Lapidus.

“Clearing forest prior to proper review of sustainability assessments is like a plane taking off in bad weather while awaiting the forecast,” said Lapidus. “It’s a strong indication that these assessments were done for show to appease their customers rather than to truly provide guidance on responsible development.”

She also criticised the company’s assessments for falling far short of Mighty’s own assessment for how much land needs to be protected. While Korindo’s assessments found 6,254.5 ha of forest in PT PAL that needs to be conserved, Mighty in its report estimated that about 26,500 ha of primary forest remain in PT PAL’s concessions.

“

We are very disappointed at Korindo’s duplicity, and urge them to immediately halt all further development.

Deborah Lapidus, campaign director, Mighty

When Korindo’s violations were first exposed, palm oil giants such as Wilmar and Musim Mas pledged to stop buying from the company; Mighty urged its current and former customers to maintain their suspension of purchases from the company.

It also wrote to the companies that buy wind towers from Korindo-owned company Kousa to suspend business with firm, as Korindo’s forest destruction is incompatible with their goals to fight climate change by producing wind energy.

These companies in October said they were conducting independent investigations into the matter, but this does not have appeared to deterred Korindo from clearing forest, said Lapidus.

“Now it’s high time for these companies to end their contracts in order to preserve the integrity of their mission to mitigate climate change and their commitments to maintain responsible supply chains,” she added.

More trouble brewing

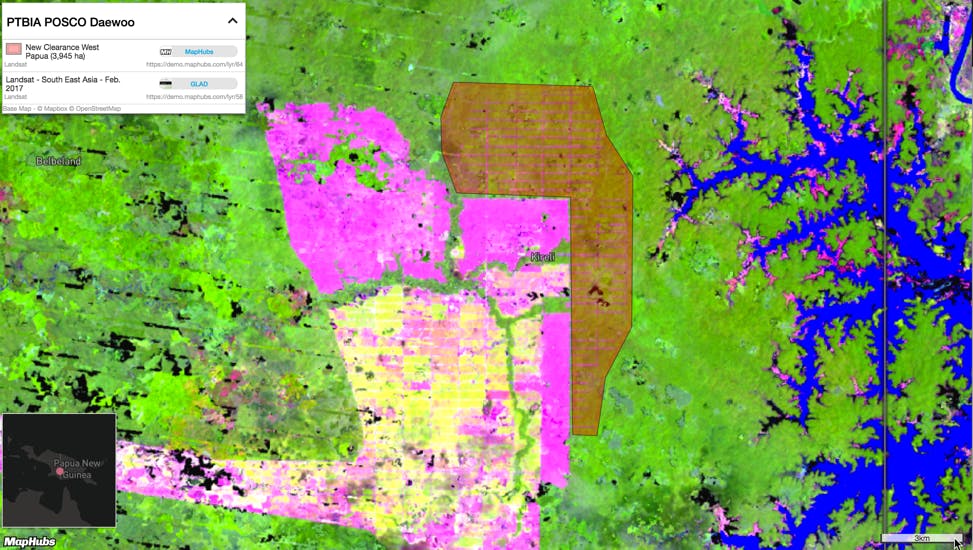

Even as Mighty sounded the alarm about deforestation caused by Korindo, it warned that another Korean palm oil company, Posco Daewoo, was preparing to clear an even greater expanse of forest in Papua. Satellite images accessed in the past month showed that Posco Daewoo had drawn plantation blocks across 4,000 hectares of its concession.

Satellite image showing plantation blocks (the areas shaded in brown) being carved in Posco Daewoo concessions. The yellow line on the right is the border between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Image: Mighty

The company is not a member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), the industry association for responsible palm oil. None of its social or environmental impact assessments are publicly available.

This land will “be imminently cleared unless Posco Daewoo’s buyers, investors, and bankers intervene right away,” said Mighty. Environmental campaigners have long attacked the company’s practices, and it has even been dropped by the Norwegian Pension Fund because of its links to deforestation.

Choony Kim, international cooperation coordinator, Korea Federation for Environmental Movements, said: “Korean companies think they can get away with deforestation in remote areas of Indonesia without being held accountable”.

“But we want to let them know that the world is watching and Korean citizens are demanding action,” he added. “These companies are bringing shame on themselves and they risk tarnishing the reputation of Korean industry.”