Energy giant Shell and Singapore’s Centre for Liveable Cities on Tuesday launched a new study that explores the energy implications of urbanisation.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Presenting the new report at a lecture held at the Ministry of National Development’s auditorium, Shell’s vice president, global business environment, Jeremy Bentham noted that urbanisation is “one of the great social phenomena of our age”.

The global urban population is expected to rise from 3.6 billion in 2010 to 6.3 billion by 2050, and the top five locations for this urban population explosion are India, China, Nigeria, West Africa and the United States. This rate is almost the equivalent of adding a new city the size of Singapore every month.

“How cities around the world develop in coming decades will determine how efficiently we use vital resources – particularly energy, food and water – and directly impact the quality of life for billions of future urban citizens,” said Bentham.

The publication, New Lenses on Future Cities, is the first in a series of supplements to the New Lens Scenarios published by Shell in March last year. Shell and CLC had signed a three-year memorandum of understanding in 2012 to collaborate on research, publications and events on urban management and solutions.

Shell has for the past 40 years published scenarios to explore alternative views of the future and create plausible stories around them. They consider long-term trends in economics, energy supply and demand, geopolitical shifts and social change, as well as the motivating factors that drive change.

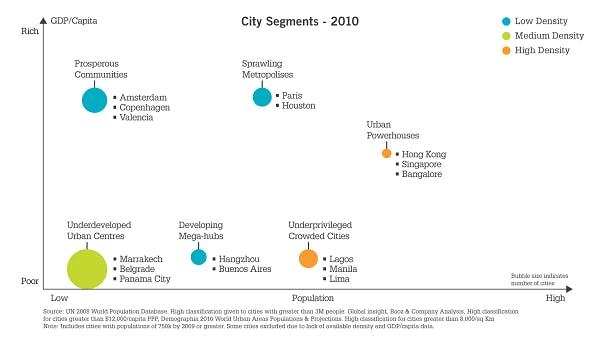

Shell’s joint research with Booz and Company also studied more than 500 cities with more than 750,000 residents and 21 megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants to identify six types of cities to “frame our understanding of energy use in cities”, the study said.

Energy use is concentrated in sprawling metropolises and prosperous communities, while the vast majority of future urbanisation is set to take place in developing mega hubs and underprivileged crowded cities.

“While every city is different, some guiding principles of ideal development exist, such as increasing compactness and more efficient integration of transport, power and heating systems,” said Bentham. “For example, our research shows that compact city design can typically reduce average car use nationally by as much as 2,000 kilometres per person annually compared to countries with low density development common in many parts of the world today.”

Applying the “lenses” that Shell has developed, the study said two typical institutional development routes evolve in response – in the first, some can adopt and reform, giving them “room to manoeuvre”.

In others, action is delayed until it is forced by growing crisis, putting cities in a “trapped transition”.

In a chapter on Singapore, the study said the city-state was falling into a trapped transition fifty years ago when it first gained independence and was facing high unemployment and poor public hygiene with the majority of its population living in slums.

But its policymakers then took decisive steps in urban planning, housing and transportation which created room to manoeuvre for its long term physical development. For example, the Housing and Development Board was set up in 1960 with a mandate to tackle the problems of housing, and strong land acquisition laws and powers of resettlement were implemented.

Today, more than 80 per cent of its citizens live in public housing which is well-integrated with nearby jobs, schools, public transport, parks and other facilities.

Bentham told the audience that core challenge for cities in the future “will be the tension between compactness and liveability… and the best of both worlds is feasible. Singapore is an example.”

Speaking at a panel discussion with Bentham, Acting Director Julian Goh of CLC - a government think tank that promotes and shares knowledge on liveable and sustainable cities - said Singapore is “humbled” to be picked as a model of good urban development.

“Singapore’s experience in urban development has shown that dynamic urban governance and integrated master planning and development are important for cites to develop room to manoeuvre,” he said.

The study also argued that new cities yet to be built can be designed from the beginning to a “compact integrated ideal”. For older cities with existing infrastructure, well targeted and affordable retrofitting will help.

Also, rather than continuing to expand city boundaries as population increases, policymakers should use regulations and incentives to encourage the “infilling” of existing infrastructure and districts, so that they become progressively more densely populated to absorb future growth.

The other challenge cities may face is resistance from residents. Cities often considered most attractive are properous with low population density, reflecting the desirability of “having it all”: proximity to other people and city amenities, while retaining plenty of personal private space, such as detached houses with gardens, said the Shell/CLC study.

But increasing density does not necessarily decrease liveability. Cities such as Singapore, London, Tokyo are examples of higher density locations with high liveability scores. As the stress on global resources increase, public expectations may change and it is possible that resource efficiency - and hence city compactness - will “begin to feature more significantly as a component of city attractiveness and liveability”, the study observed.