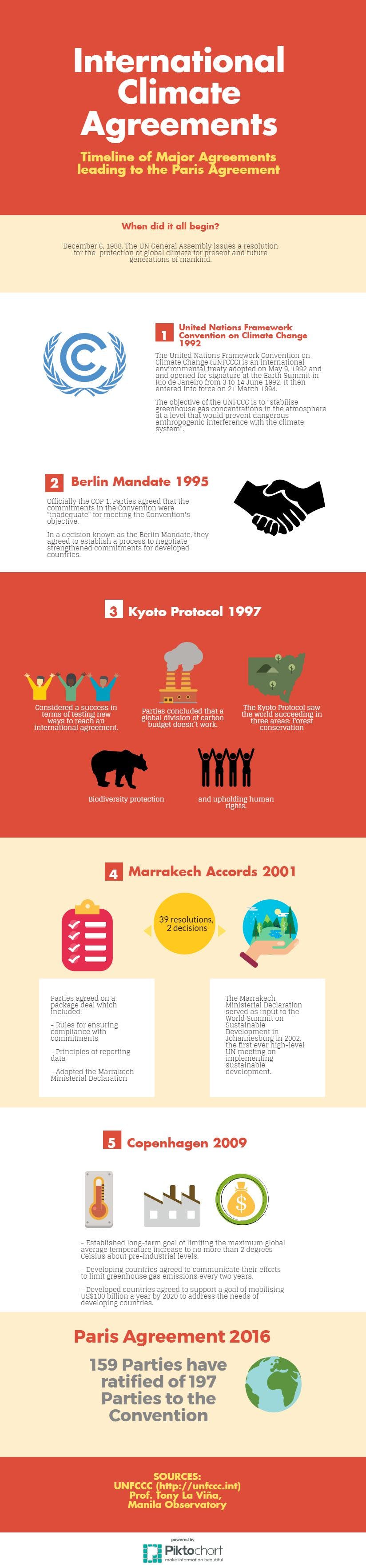

Global climate negotiations that lead to international agreements such as the historic Paris Accord, which came into force on November 4, 2016, have been happening for decades now.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But when did the political push against climate change begin? And, decades on, what have these talks actually achieved?

While the basic physics of climate change have been known for more than a century, it was only in recent decades that the fundamental science of global warming has solidified. This has given impetus for climate scientists to push policymakers to take action on climate change.

Speaking on the topic at a climate journalism course in Manila in August, organised by non-profit climate advocacy group Climate Tracker, long-time Filipino climate negotiator Tony La Viña said that the first climate negotiations began after climate scientists observed an otherwise mundane weather phenomenon: rain.

In the 1980s, Filipino weather observer Roman Kintanar, who was then the World Meteorological Organisation’s (WMO) eighth congress president, and another colleague, noticed significant changes in rain patterns, said La Viña, who heads non-profit research institute Manila Observatory.

Climate scientists observed that the rain had become so strong that it had started to seep in through their windows.

“

There is no single response to climate change – we have to continue to work on mitigation and adaptation. But now, climate justice is the way to frame adaptation and mitigation.

Tony La Viña, executive director, Manila Observatory

This simple observation led to further research, and as soon as they had gathered enough evidence, Kintanar and his colleagues at WMO decided to warn the United Nations (UN) about what they observed to be an unusual increase in precipitation.

“This was in 1988. It took a while before the world could act – four years later, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was created,” La Viña said.

Infographic by Ping Manongdo for Eco-Business

Having completed his doctorate on climate change studies at Yale Law School in the 1990s, La Viña has been on the global climate negotiations scene ever since the creation of the UNFCCC, and has become one of the world’s foremost climate negotiators, a role he has performed for 30 years.

Three periods of global climate change negotiations

1990s to 2000: Climate mitigation

La Viña recalled that the first ten years of climate negotiations, from the 1990s to 2000, were all about shaming developed countries over their greenhouse gas emissions and calling for these emissions to be reduced. This was the period known as climate mitigation, or the call to reduce emissions.

Negotiators believed then that if developed countries reduced their emissions by 30 per cent by the year 2000, the world would have a better chance of mitigating the impacts of global warming.

In particular, this meant protecting small island states from a rise in sea level. In 1994, The Alliance of Small Island States – many of whom feared they would disappear beneath the waves – demanded a 20 per cent cut in emissions by the year 2005. This, they say, would cap a sea-level rise at 20 centimetres.

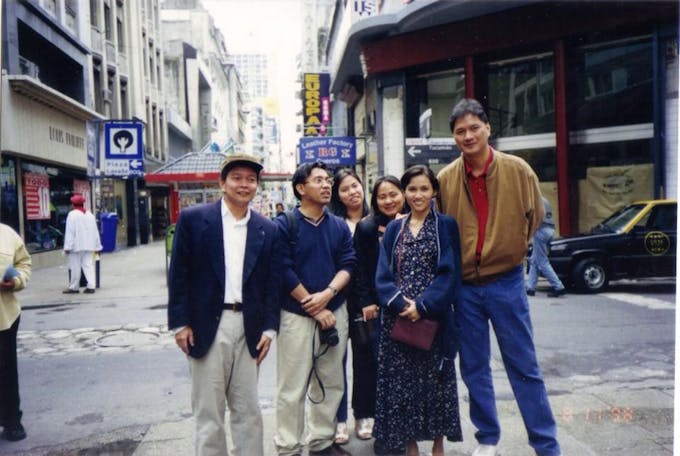

A younger Tony La Viña in Berlin with the Philippine climate negotiation team in the 90s. Image: Prof. Tony La Viña

“From the beginning, we should have insisted on universal participation. Developing countries should have played a role – they accepted the thinking that only the rich countries should act. Although morally there is some truth there,” La Viña said.

The agreements were then enshrined in the Kyoto Protocol, the treaty signed in the Japanese city on 11 December 1997. La Viña said the biggest challenge was to push the United States to agree to reduce their emissions. That failed.

“The US did not listen under the first George Bush, and the second George Bush put the nail into that failure by refusing to participate in the Kyoto Protocol,” La Viña said, referring to US presidents George H.W. Bush (1989 to 1993) and George W. Bush (2001 to 2009).

These first few international agreements lacked obligations that each country would commit to meet. Instead, they were just moral agreements that did not have the effect of bringing nations together to act, La Viña recalled.

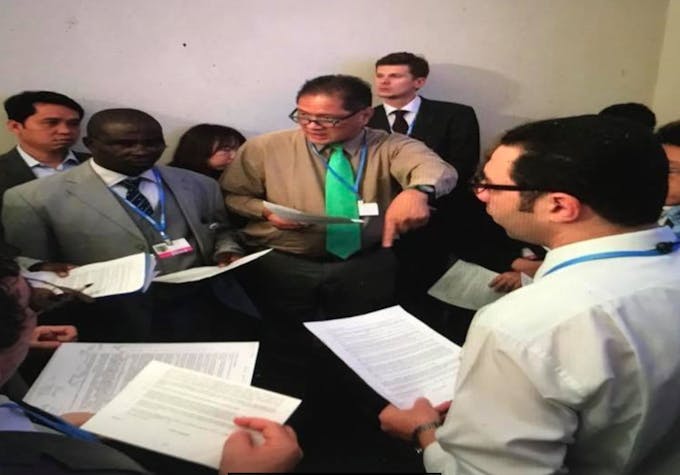

Facilitating agreement on sections of the Preamble on the Paris Agreement and on the decision on REDD-plus finance in Durban, 2011. Image: Prof. Tony La Viña

Late 2000s to early 21st century: Climate adaptation

When negotiations with the US failed, it became difficult to take climate action forward.

But there was a silver lining to American reluctance; the world’s nations came to recognise the need for adaptation, which called for countries to prepare and build resilience to the effects of climate change.

“It made me realise that the worse effects of climate change were yet to come,” La Viña said.

He later went to work with global think thank World Resources Institute (WRI), which runs climate adaptation programmes around the world.

La Viña said it is important for countries to reduce emissions and prepare for impacts that will get worse over the course of time.

“What we do today doesn’t make a difference tomorrow or in the next five years – we are trying to avoid the worst scenarios by 2050.”

Speaking from the perspective of the Philippines, a country highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, La Viña said having known about climate change much earlier on could have helped the country prepare for the worst disasters that have battered the archipelago in recent years.

“What we’ve seen over the last ten years—Yolanda, Sendong and Pablo—would not have been avoidable, even if we took action ten years ago. We should have done something in the 80s to avoid Yolanda, but we were not yet fully aware of climate change in the 80s,” he said.

Prof. Tony La Viña (in green) and participants to the 2016 Climate Reality training in Manila pose with Al Gore. Image: Prof. Tony La Viña

La Viña was referring to the biggest typhoons to have hit his country. Typhoon Yolanda, known internationally as Haiyan, claimed the lives of some of his relatives in Tacloban, the city worst hit by the devastating storms of 2013. Yolanda was the most intense typhoon ever to make landfall.

21st century to present times: Climate justice

La Viña shared that at present, global climate negotiations are working towards an agreement on climate justice.

Climate justice means that richer countries, which are usually the heaviest emitters, should pay more for emissions than poorer countries, which emit less. And poor countries should get help from rich countries to reduce their emissions and prepare for, and adapt to climate threats.

“There is no single response to climate change – we have to continue to work on mitigation and adaptation. But now climate justice is the way to frame adaptation and mitigation,” he explained.

Professor Tony La Viña with Southeast Asian climate journalists in Manila, August 4, 2017. Image: Renee Karunungan/Climate Tracker

La Viña said that climate change negotiations are not only about reducing emissions and preparing for climate-related disasters. Rather, it is about nations coming together to act for the environment, to lift people out of poverty, and to champion the wellbeing of humanity and the planet.

While he acknowledged that the US withdrawing from the Paris Agreement would impede the speed of global climate action, it will not prevent other countries from rising to the challenge.

If countries continued to decarbonise, then emissions can be prevented from reaching critical levels, La Viña said.

He stressed the importance of achieving a balanced energy mix, keeping the use of fossil fuels to a minimum while ensuring a reliable, secure energy supply.

“A country like the Philippines should never endanger its power supply. If we did, it’s the worst thing we could do to the environment. That’s why we had to resort to using coal and diesel generators in the first place,” La Viña said.

In conclusion, La Viña said climate journalists have an important role to inform, educate, analyse and agitate people about climate change, but above all, media must inspire people to take action.

The biggest climate story is not about catastrophes, it is one of hope, La Viña said.