Vegetarian? Omnivore? Vegan? What should we eat if we want to feed a growing population while minimising the need to farm more land? We know that meat-based meals require more farmland than plant-based ones. But which diet is the best fit for the mix of croplands and grazing land that supports agriculture today? That’s a different question with a potentially different answer, since much of the land we use to produce our food is better suited for grazing livestock than growing crops.

A new study published in Elementa explores this perplexing question of the “foodprint” of different diets. Researchers calculated how much land is needed to feed people under 10 diet scenarios ranging from conventional American to vegan. The study considered land currently farmed throughout the entire continental United States and looked at not only the amount of land needed to support each diet, but also how much of the available land each scenario could use.

The 10 scenarios included a diet based on current U.S. food consumption patterns and another that reduced fats and sweeteners to bring the calorie level in line with U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The remaining eight scenarios maintained healthy calorie levels but moved toward increasingly vegetarian eating patterns, including ovo-lacto vegetarian, lacto vegetarian and vegan.

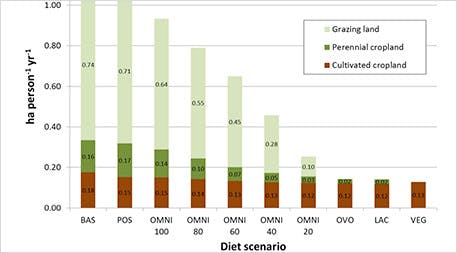

The baseline diet — what Americans are eating today — required the most land at 1.08 hectares (2.67 acres, or more than two football fields) per person per year, followed by the reduced-fats-and-sweeteners diet at 1.03 hectares (2.55 acres) per person per year. Land requirements decreased steadily as the proportion of food derived from animals declined, with the three vegetarian diets requiring 0.13 to 0.14 hectares (0.32 to 0.35 acres) per person per year.

The amount of grazing land, perennial cropland and cultivated cropland needed to support different diets varies widely. Image courtesy of Elementa via Ensia.com

Since production of different types of food requires different types of agricultural land, researchers distinguished among three distinct categories of land: grazing land, cultivated cropland and perennial forage cropland. They found that the five diets containing the largest quantities of meat used all of the available cropland and grazing land. The five diets containing little or no meat still used the maximum available area of cultivated cropland but varied widely in their use of forage and grazing land. The vegan diet relied solely on the land suited to growing crops, using none of the available grazing or forage land.

When the number of people who can be fed from the available agricultural land was estimated, results revealed that reducing meat in the diet increases the number of people who could be supported by existing farmland.

Estimates of the number of people who could be fed ranged from a 402 million people for the “business as usual” diet to 807 million people in the lacto vegetarian scenario. The vegan diet, surprisingly, fed fewer people than two of the omnivore diets and both of the other vegetarian diets, suggesting food choices that make use of grazing and forage land as well as cropland could feed more people than those that completely eliminate animal-based food from our diets.

The researchers concluded that a strategic shift toward a plant-based diet could reduce the amount of land needed to feed U.S. consumers and at the same time increase the number of people who can be fed from our agricultural resources. The result could be more food — without the need to clear more land — for hundreds of millions of people around the globe.

This piece was produced in collaboration with the academic journal Elementa. It is based on “Carrying capacity of U.S. agricultural land: Ten diet scenarios,” published July 22 at Elementa.

This story is published with permission from Ensia.com