Abbas Pada, 45, pulls rickshaws through the streets of Dhaka, Bangladesh for a living. Every evening, he returns to his living quarters in a slum, where he calculates how much of the day’s meagre earnings goes to food and other necessities.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Life was not always like this for Pada, who until 2011 lived with his wife and three children in Nayakata village in south Bangladesh. His work as a fisherman and day labourer could support his family comfortably, but this stable existence came to an abrupt end when a nearby river - swollen due to rising sea levels - eroded the embankment where the Pada family lived, taking their house with it.

Reeling from the loss of his home, Pada moved to a nearby village to look for work. But employment proved elusive, and he had to take out a high-interest loan to support himself and his family.

To pay off this debt, Pada moved further to work in Dhaka, while his family stayed behind in Nayakata. In the city, he lives in squalor and struggles to make ends meet. He tells Eco-Business: “It is my dream to return to my village, but I can’t save enough money to go back”.

Pada’s plight is shared by millions of people in poor communities around the world, whose safety and economic security are undermined by coastal erosion, droughts, natural disasters, and other impacts of climate change.

Abbas Pada, 45, stands in the village of Nayakata, Bangladesh, where a swollen river washed away his home. Image: ActionAid Bangladesh

One highly visible consequence of such climate-related events is the current European migrant crisis, say experts.

The International Organization for Migration estimates that about half a million people from Africa and the Middle East have crossed the Mediterranean Sea so far this year. Many of them are fleeing a civil war in Syria and the expanding presence of the terror group Islamic State.

Three-year-old Aylan Kurdi, who was pictured by international press washed up dead on a Turkish shore, has become the poster child for the horrifying experiences faced by migrants undertaking this journey.

New research published in March by various American universities traces the unrest in Syria to a record-breaking drought that plagued the country from 2006 to 2011, killing crops and forcing farmers into the city. Its authors say it catalysed underlying dissatisfaction with the government into full-scale civil war.

The migrant crisis unfolding in Europe could be a harbinger of things to come in Asia Pacific - a region most prone to natural disasters - if no preparatory measures are taken to tackle climate-related crises, say experts.

In fact, Southeast Asia experienced a similar situation earlier in May when the discovery of mass graves of human trafficking victims in Thailand and Malaysia prompted the authorities to tighten their borders, leaving boats full of Bangladeshi economic migrants, along with refugees from Myanmar’s Rohingya ethnic group, stranded at sea for weeks.

Bangladesh has been ranked by English consultancy Verisk Maplecroft as the world’s second most vulnerable nation to climate change.

Harjeet Singh, international climate policy advisor at non-profit ActionAid, tells Eco-Business that in Asia, people are already migrating for economic opportunities, but environmental degradation and natural disasters are important driving factors too, which will only intensify with climate change.

Asians on the move

For centuries, people have migrated within and across continents due to a mix of social, political, and economic factors. But climate-linked migration is unique because these movements are involuntary and those who move are among the most vulnerable in society, says a 2012 report by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Bartlet Edes, director of ADB’s poverty reduction, gender, and social development division, says that it is not possible to isolate environmental problems as the reason people move, but “it is a factor that will become increasingly important with worsening climate change”.

The two top climate-linked reasons why people move are sudden natural disasters and the slow-onset environmental degradation, says the ADB.

According to Switzerland-based Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), disasters drove 19.3 million people from their homes last year - that’s one person displaced every second.

More than 90 per cent of them - or 17.5 million - were forced to move by weather-related phenomena such as floods, storms, and droughts, while geophysical disasters such as earthquakes were responsible for the rest.

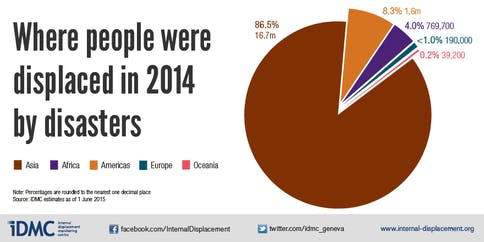

Asia was the most vulnerable region, accounting for 87 per cent of all people displaced. China, India, and the Philippines were the worst affected.

These figures do not paint a complete picture of climate-induced migration in Asia. As ADB notes in its report, it is difficult to quantify movements within borders and to keep track of temporary displacement and seasonal migration. Also, because the reasons people move are such a complex mix of factors, it is difficult to decide what counts as climate-linked migration.

Out of the 19.3 million people displaced by disasters in 2014, almost 87 per cent were located in Asia. Image: International Displacement Monitoring Centre.

But IDMC’s data is a good proxy which can give clues about the magnitude of the broader trend, says Edes.

Beyond disasters, environmental degradation is also a key driver. ActionAid’s Singh says the most vulnerable are those whose livelihoods are significantly dependent on the weather - farmers, fisherfolk and animal herders, for example.

Jonatan Lassa, research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, notes that subsistence farmers who only grow enough to feed their family usually have the least amount of food or money saved up, and are at high-risk of having to leave their farms if harvests fail.

Climate migration trends

Despite the uncertainty surrouding the statistics on climate-related migration, experts are confident of two things: firstly, that such migration is typically a domestic phenomenon - meaning, they are likely to move within their country.

And secondly, rural-urban migration is the most common movement among those affected. People in low-lying urban areas are also prone to being driven from their homes by floods.

Singh notes that many new arrivals to Asia’s crowded megacities may end up trapped in a cycle of high expenses and low earnings. Others may fare even worse: A recent report on Indian news site Scroll.in shows how migrants from parched villages in Odisha state end up as bonded labour in urban brick kilns.

Another 2012 story by the Thomson Reuters Foundation exposes how repeated crop failures in Andhra Pradesh state drove male farmers to suicide, and women into Hyderabad city to become sex workers.

These dangerous working conditions are often compounded by everyday indignities like having to sleep, bathe, and defecate on the pavement, facing regular abuse from police, and living without basic provisions like an identity card or banking services.

A typical slum in Ahmedabad, India. When migrants move from villages to big cities, housing in marginal areas like slums is all they can afford. Here, they lack access to basic amenities such as personal hygiene facilities and clean running water. Image: Matyas Rehak / Shutterstock.com

Singh says that even if these people earn slightly more than what they did in the countryside, life in villages offer a more secure existence and they would rather not move, given the choice.

But climate-induced migration can also have positive effects. ADB’s Edes says: “Migration, properly managed, can help promote climate change adaptation, and be a win-win situation for destination and migrant-sending communities.”

For one thing, many essential services in Asian cities are provided by migrants. They often work as construction workers, domestic helpers, and food sellers, filling labour gaps and earning money for their families.

The money sent back by migrants also support home economies. For example, remittances by overseas workers from Bangladesh and the Philippines totalled US$14 billion and US$25 billion respectively in 2013, according to The World Bank.

Nadeeka Abeykoon Mudiyanselage, 37, is one migrant who eked out a better life after leaving home. She spent more than 13 years toiling in padi fields in Sri Lanka, during which she had to borrow money for expenses such as labour costs, fertiliser, and to offset lost income from low crop yields during bouts of dry weather.

Eventually, the debt grew too debilitating and Mudiyanselage found work as a domestic helper in Singapore. After a few years in difficult circumstances such as long working hours and having no days off for a year, Mudiyanselage is now an assistant in a centre for troubled girls, where her working conditions are better and she earns enough to support herself and her teenage son back home.

“I am much happier in my new job, and hope to continue working in Singapore,” she tells Eco-Business.

Boosting resilience

Experts in this field say that the fate of these migrants - and whether they stay in or leave their country - when facing climate-related events depends largely on the response of the international community, governments and business.

More broadly, governments need to re-evaluate current social security systems to provide people with support during tough times, says Singh.

One basic intervention is to boost the resilience of local communities so they can adapt to a changing climate. This can involve, for instance, developing saline-resistant crops - which will grow even as salty sea water encroaches into farmland - or strengthening disaster warning systems.

As traditional farming practices become less relevant in the face of unpredictable weather patterns, the government can use technology and science to help farmers determine when to plant and harvest crops to boost their survival odds.

Two initiatives which have made a difference to rural dwellers in India are the implementation of a National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in 2005; and the practice of setting up ‘cattle camps’ during droughts, he says.

The former is a labour regulation which guarantees at least 100 days of paid employment in a financial year to every household where adults volunteer to do unskilled manual work. This payment is a boon, says Singh, and helps farmers stay in their villages instead of moving to the city in search of more income.

Cattle camps, meanwhile, protect a farmer’s most valuable asset - livestock. During a drought, farmers may struggle to feed their animals, and end up selling them at rock-bottom prices to slaughterhouses.

Charitable foundations have sometimes intervened to offer free cattle feed, water, and temporary shelter to drought-stricken smallholders, which help to keep the farmer’s cows - and livelihoods - alive.

Edes adds that affordable insurance is also important for community resilience. It prevents farmers from sliding into poverty if they have a bad harvest, fall sick and cannot afford the medical bills, or face other unexpected setbacks.

But traditional private insurance is often unaffordable for poor communities, and government spending on social protection can plug this gap, he notes. Cash transfers to poor families and job skills training are also important elements of a wider social safety net, he adds.

Social protection goes beyond helping rural communities become resilient. By ensuring that the poor have access to health coverage, basic insurance, identity registration, and financial services among other things, governments can also improve the lot of new arrivals to a country or city, says Singh.

The billion dollar question

But any talk of investing in social welfare and resilience raises the billion-dollar question: Where will the money come from?

The answer lies in a variety of sources, says Edes. While the government usually foots the bill for social protection, it can also create frameworks that encourage private sector involvement and public-private partnerships, he adds.

The international donor community should also contribute, he says.

But this is a complicated affair. Singh, who lobbies for pro-poor policies at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations, observes that money is at the crux of disagreements between nations.

Developing countries insist that richer nations bear a greater historical responsibility for emissions and should therefore fund climate adaptation, while the latter group maintains that emerging countries must answer for their rapidly growing emissions.

Nevertheless, rich countries have agreed to support international financing mechanisms such as the Adaptation Fund, and the Green Climate Fund. Since 2010, the Adaptation Fund is financed by government and private donors, and has since 2010 allocated about US$318 million to climate adaptation and resilience activities.

The Green Climate Fund, based in South Korea, has seen 30 countries pledge about US$10 billion to help developing countries cut emissions and prepare for climate change since last year.

Legislation and the private sector

Experts add that there are also many loopholes in the global laws governing human mobility.

Marine Franck, climate change consultant at the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees (UNHCR) notes that a key challenge lies in identifying such displaced persons, particularly in the context of climate change.

There is currently no international framework addressing cross-border disaster-related displacement, she adds.

Indeed, if someone is forced from his home due to climate-related events, he will find no protection from the international system because there is no such thing as a “climate refugee” in legal terms.

Cosmin Corendea, senior scientist and legal expert at the Bonn-headquartered United Nations University’s Institute for Environment and Human Security, explains: “To gain refugee status, you have to go through the UNHCR process. If you mention that you left home because of something like a hurricane, they will send you back, or may grant asylum based on humanitarian grounds.”

There is also no dedicated agency or coordinated global effort to address the needs of climate migrants.

To highlight these problems, UK-based non-profit Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) released a report called Falling through the cracks, which proposes a new global framework to plug the “protection gap” for climate refugees.

Falling through the cracks from Environmental Justice Foundation on Vimeo.

Among the report’s key recommendations are the appointment of a UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Climate Change, who would guide international action on the issue.

Steve Trent, executive director of EJF, tells Eco-Business that while this Rapporteur may not have much decision-making authority, he or she could “provide a driving force for debate, helping to drive broader consensus on the need for action in this pressing matter”.

There is also a “pressing need to give climate refugees a clear legal definition and in this, provide a framework in which their basic human rights can be ensured,” he adds.

Meanwhile, in the absence of such institutions, the UN’s newly-adopted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – a set of 17 goals and 169 targets on social and economic progress – give observers cause for hope.

RSIS’s Lassa notes that the terms “climate” and “disaster” appear multiple times in the SDG text, and this may influence Asian governments to develop a proper migration policy.

Resources would then be allocated to help migrants move safely and successfully resettle, he says.

Countries can also work together to ensure that migrants can gain employment, ADB’s Edes says. An example of this is a decision by Japan to let nurses from Indonesia and the Philippines work in the ageing nation.

Involving the private sector in building resilience and promoting safe migration is also necessary.They can invest in basic infrastructure such as roads and hospitals to improve rural living conditions and create jobs for migrants.

But above all, “businesses should reduce their carbon emissions and not open up new risks”, says Singh. Practices such as dumping untreated waste into waterways and developing buildings on wetlands, which prevents flooding, undermine community safety and must stop, he adds.

Beyond environmental and social responsibility, businesses can also lend their core skills to non-profit efforts which address climate change, social protection, and safe migration, says Singh. He cites a recent collaboration between ActionAid and the Economic Intelligence Unit to develop a data tool to measure women’s resilience in South Asia as an example.

Against a rapidly changing climate, there is mounting pressure on businesses and governments to act more responsibly.

It remains to be seen how migration will affect Asia’s social and political landscape in years to come. For the region, “migration trends depend on what countries, governments, businesses, NGOs, and communities do from this point forward,” says Edes. “The future is not yet written.”