Adelaide, the capital city of South Australia, has the potential to be a living laboratory for experiments in green urbanism. There are already many examples of sustainable design in the Adelaide city centre and the latest of these is the SAHMRI Medical Research Building. Is it a spaceship piloted by a friendly alien, a metallic pine cone or giant cheese-grater?

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

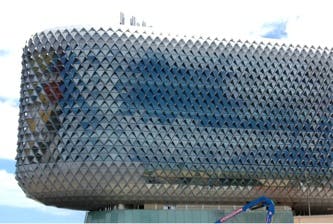

SAHMRI stands for South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, a dedicated flagship research institute, and its structure on North Terrace is not designed to blend into the Adelaide skyline – it’s a floating object. The building is lifted by massive columns, opening it to the public as well as users, allowing for greater movement through the site. The 25,000-square-metre facility is located adjacent to the new Royal Adelaide Hospital, sharing its forecourt entry.

The institute will conduct collaborative interdisciplinary research with SA’s three universities and is the first stage of a new health and bio-medical precinct. It promises to be one of the most amazing research and innovation communities in Australia.

Working under the same roof, researchers from all three South Australian universities will forge new relationships and collaborate with other organisations to make SAHMRI a vibrant, globally recognised research institute. There are numerous advantages to bringing a range of research focus areas under one roof, including sharing the cost of expensive technology, state-of-the-art laboratories, improved sharing of research techniques and outcomes, and synergies from knowledge sharing.

“

Adelaide’s per capita CO2 emissions are exceptionally high by international standards: over 28 tonnes of CO2 per person per year … The main contributors to this were increases in population, energy-intensive transport, and commercial and residential buildings’ air-conditioning. Adelaide is on a trajectory to become an ecologically sustainable city but it needs more outstanding green architecture and low-carbon precincts

Thousands of staff will be employed across the health and bio-medical precinct and their presence will boost the city’s economy and vibrancy.

The building makes the most out of its exposed location. It has an envelope (outer shell) of diamond-shaped façade elements wrapped around its exterior. The facade covers the entire surface and responds to sunlight, heat load, glare and wind, while maintaining views and daylight. To reduce heat load and glare, sunshades have been designed and orientated for optimum thermal and light efficiency and their sizes vary for that reason.

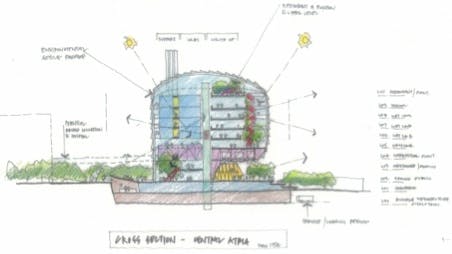

The architects enlisted environmental consultants for intensive analysis of their design. They used computer modelling tools to integrate environmental requirements into the façade design, and to ensure that the building optimises its solar orientation through passive design of floor plates that provide maximum daylight where needed. For instance, the enclosed lab support spaces are located along the western façade to provide protection from the harsh afternoon sun.

Parametric design produced by computational modelling tools (such as Maya or Rhino) has become the architecture profession’s current obsession. The good thing about parametric design is that we can now rework and remodel a building’s shape to improve its energy performance, orientation and geometric parameters, allowing us to test different design options very quickly. Building information modelling (BIM) makes sharing this 3D information with structural and environmental engineers easy.

For this building, parametric modelling has been used to optimise the envelope to perform more environmentally sustainable. Australian project architects Woods Bagot says the key to the success of SAHMRI is a new and liberating lab typology that promotes collaboration and openness. The architects suggest that the building design and workplace environment will foster collaboration between researchers, achieved by the introduction of glass partitions, open atria and bridges, as the visual connection between floors and an interconnecting spiral stair will encourage connectivity and collaboration.

The laboratory building also features an ecologically sustainable concept beyond the comfortable internal working environment. It minimises the use of energy through an energy-efficient heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system, with high levels of outdoor air supply (something that is still unusual for laboratories); intake of fresh air is through the cooler plaza gardens and a sub-labyrinth to cool the air naturally. Other features include rainwater harvesting and the re-use of processed water; and an intelligent integrated building system to improve energy efficiency and provide real-time measurement of operational measures, such as energy and water consumption (e.g. no potable water is used in cooling towers or for toilet flushing). The operational costs of such a facility over 20 years can easily be higher than initial construction costs, so hopes are high in regard to the intelligent building system.

In keeping with South Australia’s history of progressive reform, Adelaide (1.2 million population) has frequently led Australia in implementing environmental sustainability initiatives. To achieve more sustainable cities, urban designers must understand and apply guiding principles, adapted to local contexts, in a systematic way; for instance, by applying the principles of green urbanism. In 2008 I developed the concept of green urbanism based on a holistic systems thinking approach that interconnects urban ‘eco-regeneration’ with changes at both the building and neighbourhood scale. The interconnected principles offer a guide for managing a city’s energy, water, food, material flows, transport, housing, work and recreation needs through education, behaviour change and creative leadership (see diagram). Understood holistically, they provide a conceptual model for creating the city of tomorrow through zero-emission and zero-waste urban development. In addressing some of the environmental challenges cities face, the principles could guide Adelaide’s sustainability trajectory over the coming decade and offer an example for other cities to emulate.

The Green Urbanism wheel, developed by the author with indicators to measure sustainable design.

Adelaide’s per capita CO2 emissions are exceptionally high by international standards: over 28 tonnes of CO2 per person per year. It is estimated that, between 2002 and 2012, the CO2 emissions per capita increased by around 15 per cent. The main contributors to this were increases in population, energy-intensive transport, and commercial and residential buildings’ air-conditioning. Adelaide is on a trajectory to become an ecologically sustainable city but it needs more outstanding green architecture and low-carbon precincts.

SAHMRI’s impact on the art of making cities and sustainable architecture in Adelaide is likely to be profound. The giant grater, the floating pine cone, the fishnet or spaceship – whatever nickname sticks, this striking addition to the Adelaide skyline is the most exciting new building in town, set to make an impact well beyond its appearance.

The new SHAMRI building on Adelaide’s North Terrace is the first piece of the North Terrace Health Precinct mosaic. The hood shade of each window is in a different size depending on sun exposure. Images: Steffen Lehmann, Nov 2013

Cross section showing the atrium and the environmental performance of the envelope. Image courtesy of the architects, 2013