Greenwashing reached pandemic proportions in 2021 as businesses and governments raced to tell the world how much they care about people and planet, with varying degrees of credibility.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Every type of brand, from oil-rich governments to canned water manufacturers, tried to jump on the Covid-19-inspired sustainability bandwagon with a blizzard of net-zero, plastic-neutral, palm oil-free or gender-inclusive claims. So many companies said that sustainability is at the heart of everything they do, that they started to sound as if they were reading from the same greenwashing manual.

Levels of greenwash got so bad this year that the public relations industry launched a working group in Singapore in July to figure out how to control it. Six months later, nothing has emerged from the Public Relations & Communications Association of Southeast Asia, and the working group is itself starting to feel a bit greenwash-y.

In 2020, Eco-Business counted eight examples of brands called out for making sustainability claims that did not stand up to scrutiny. This year, we have found 11, detailed in the following list of dubious claims and marketing spin.

Tree-planting in the desert

Saudi Arabia has said it plans to plant 40 billion trees in a region that is mainly desert. Image: Flickr

Saudi Arabia announced in March that it would be planting 50 billion trees as part of a plan to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2060. There was very little detail given about how the world’s largest reforestation programme would work in a country with limited water resources. “Greenwashing Joke of the Day, courtesy of number 2 top oil-producing country, which apparently wants to plant 10 billion trees even though it doesn’t have a single river,” tweeted Assaad Razzouk, chief executive of Gurīn Energy.

Saudi’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman said the country planned to continue to extract hydrocarbons while reducing its own emissions through means such as carbon capture, use and storage technologies (CCUS) and would be creating a “circular carbon economy”. Matthew Archer, a researcher at the Graduate Institute Geneva, told Al Jazeera: “It’s absurd to think that an economy based on the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels can be ‘circular’ in any meaningful sense of the word. The only way it works is if you rely on technologies that don’t exist yet. These initiatives are … full of language that’s as ambitious as it is ambiguous, with very few concrete plans and no accountability mechanisms.”

The Alliance to Produce A Lot More Plastic Waste

The Alliance to End Plastic Waste has been called out as a “distraction” to Big Oil’s expansion plans. Image: endplasticwaste.org

The Allliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW), a Singapore-based non-profit backed by big oil and chemical companies such as Shell, ExxonMobil, and Dow that launched in 2019, claims to be spending US$1.5 billion on cleaning up plastic waste in developing countries. But an investigation by Reuters in January highlighted not only the failure of one the Alliance’s flagship projects to clean up the Ganges river in India, but the fact that these companies are planning to dramatically ramp up plastic production, which will fuel the plastic pollution crisis. Greenpeace has called AEPW a “distraction” from Big Oil’s expansion plans.

In November, AEPW published a story on its website headlined Why proper waste management is more important than going plastic-free, which argued against bans or other means of reducing plastic production. Tom Peacock-Nazil, co-founder of Seven Clean Seas, an ocean clean-up organisation, commented on LinkedIn that AEPW’s article was unbalanced “propaganda” that made AEPW seem like a plastic industry lobby group.

DeepGreenwash

The Metals Company claims to be mining metals from the sea floor responsibly. Image: The Metals Company

A slickly produced video posted on LinkedIn features animated explosions in land-based mines and warns viewers about the dire consequences of mining the metals needed for the energy transition. “Nature disappears, humans suffer, Earth suffers. But there’s another way,” purrs the narrator in the ad for The Metals Company, which until a recent merger was known as DeepGreen, a Canadian mining company which claims to be able to responsibly suck up potato-sized metal nodules lying on the sea floor. “If we use them to make a billion electric car batteries, we can dramatically reduce our environmental and social impact for the whole planet. We’re building a world where metals are not mined and dumped, but rented and returned,” says the narrator.

But not everyone is convinced that deep-sea mining is necessary or a better alternative to land-based mining. “Oh, sure! Let’s rape another part of the earth in order to make things “cleaner”. This kind of thinking is what got us here in the first place,” said one commenter on LinkedIn. “Be cautious! Deep sea mining is connected with a large number of concerns that currently heavily outweigh any greenwashing arguments presented here,” said another, referring to calls from scientists, environmentalists and even businesses to ban deep-sea mining, because of the environmental impact of mining an ecosystem about which less is known than the surface of the moon.

“I’m a paper bottle” (but also a plastic bottle)

The packaging of Korean cosmetics brand Innisfree’s face serum had “Hello, I‘m Paper Bottle” written on the side. But the paper bottle was revealed to have a plastic lining by waste-free group No Plastic Shopping. “I felt betrayed when finding out that the paper bottle product was a plastic bottle,” the post read. The user also filed an official complaint to a consumer centre against the given product’s so-called “green washing” labelling.

Innisfree’s plastic bottle covered with a “Hello, I’m Paper Bottle“ label. Image: No Plastic Shopping

Carbon neutral hydrocarbons

Shell’s Helix Ultra car oil… now carbon neutral. The firm was ordered to stop claiming its oil was carbon neutral in the Netherlands in March.

Carbon neutral oil — yes, as bonkers as it sounds. At the start of the year, oil companies (United States-based Occidental Petroleum was first…) started branding their barrels carbon neutral because they claimed to have bought sufficient carbon offsets to account for the carbon emissions of their hydrocarbons. Shell did the same, using PR firm Edelman to pitch its “carbon neutral” Helix Ultra car oil (the same oil for sale in Shell’s award-winning eco-brick stores) in Singapore with the following: “If you are looking to do features on how one can take a step forward in the mission towards a more sustainable future and lead an eco-friendly lifestyle, we feel that Shell’s carbon neutral Helix Ultra lubricants will be a good addition.” Declaring fossil fuels as carbon neutral is like “a tobacco company saying they sell nicotine-free cigarettes because they paid someone else to sell some chewing gum,” David Turnbull, a spokesman for Washington-based advocacy group Oil Change International, told Reuters.

Three stripes — and you’re out of credibility

Adidas’ Stan Smith shoes were called out for claims that they were 50 per cent recycled. Image: Adidas

The brand with the three stripes, Adidas — supposedly one of the eco darlings of the fashion industry — was found guilty of making false and misleading sustainability claims by an advertising ethics jury in France in September. The German sportswear brand was shot down after its “50 per cent recycled” claims for its classic Stan Smith shoe were found to be vague — did the company mean that half of the materials used to make the sneakers are recycled or that they can be recycled after use? And if so, how? The complainant also said that the product’s “End plastic waste“ logo is dodgy as it is unlikely that wearing a pair of Stan Smith sneakers made from material that isn’t fully recycled will bring an end to plastic pollution.

Oil is a ‘clean fuel’

Santos is aiming to be net-zero by 2040. ACCR says the plan is not credible, as the company aims to expand fossil fuels extraction over time.

Australian oil major Santos was taken to court in August over claims it made that it produces “clean energy” and aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040 — by relying on unproven carbon capture technology. The shareholder activist group Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) also took issue with Santos describing the fossil fuel natural gas as a “clean fuel” in a sustainability report. Dan Goucher, ACCR’s director of climate and environment, called the claims “completely unjustified”.

The most sustainable packaging in the world

Aluminium is greener than plastic, right? This is what the aluminium can industry wants consumers to believe, with a raft of new canned water brands, such as Vietnam’s Ball Corporation’s BeWater product and US brand Ever & Ever, making claims that aluminium is “infinitely recyclable” and so is better for the environment than plastic bottled water. “Our mission is to eliminate single-use plastic bottles by making water better,” says BeWater on its website. “BeWater is an environmentally friendly, socially sustainable, and convenient alternative to plastic-bottled water.”

But this claim is “pure fantasy” and “not in line with facts,” says Stephan Ulrich, regional programme manager of the International Labour Organisation in Vietnam. Aluminium may be highly recyclable, but there is not enough recycled material to meet demand, and mining the materials needed to produce aluminium is extremely energy and water intensive. From a carbon and pollution perspective, there could be no worse material to make a single-use container from than aluminium. “Let alone the idea that shipping drinking water around the world makes any sense whatsoever,” says Ulrich.

‘Sustainable’ loan for coal port

A sustainability-linked loan for the world’s largest coal terminal, Port of Newcastle. Image: Discoverytheport.com.au

National Australia Bank (NAB) was given an ironic thumbs up by environmental group Market Forces in June for describing a AU$515 million (US$374 million) loan awarded to the world’s largest coal export terminal, Port of Newcastle in New South Wales, as “sustainable”. The sustainability-linked loan came with incentives for hitting certain environmental and social targets, such as improving the efficiency of the terminal. “The micro-improvements in emissions efficiency at the port ignored the stampeding elephant in the room – 95 per cent of the facility’s exports are thermal coal,” according to commentary in The Australian newspaper.

Equinot-zero

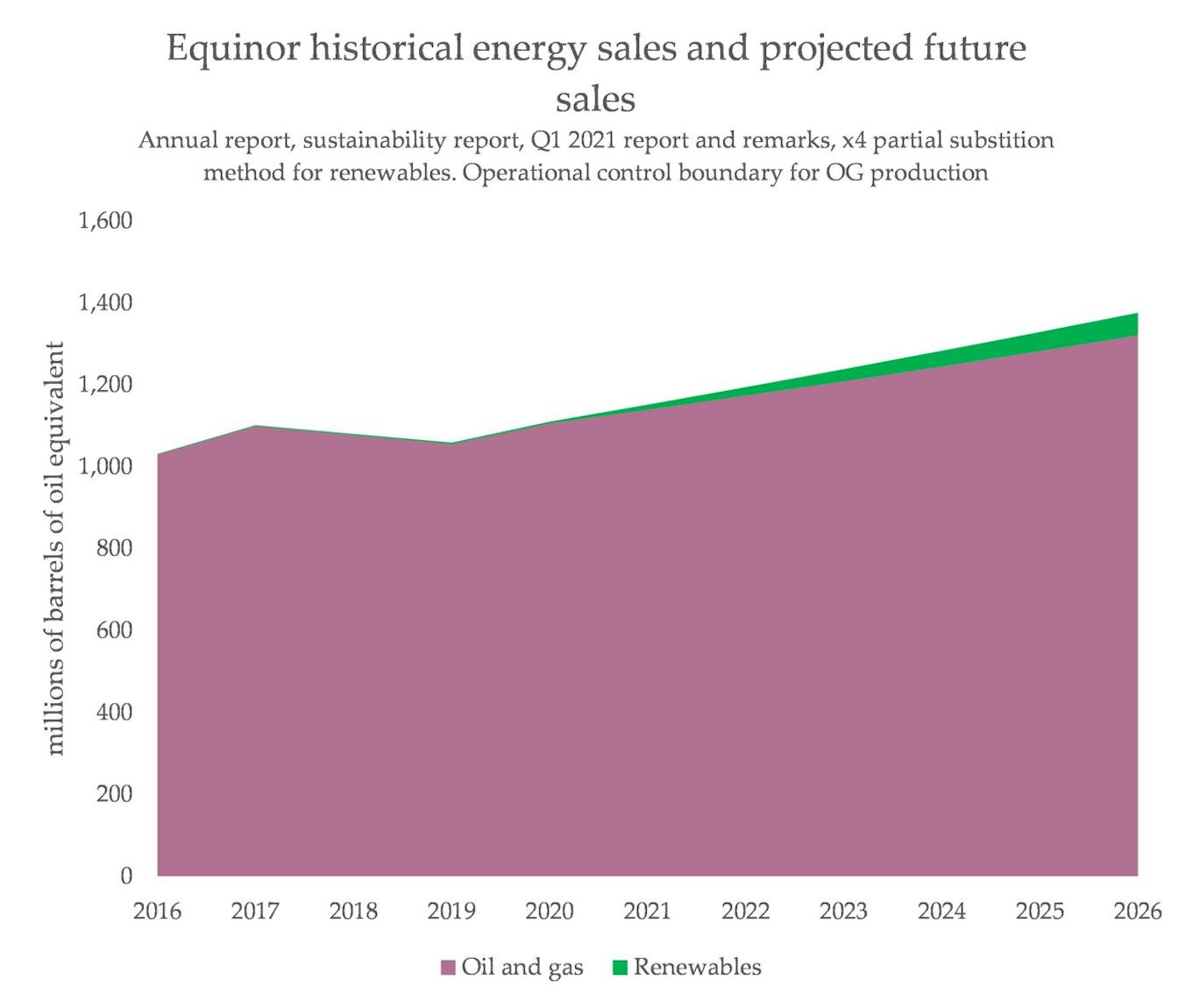

What oil major greenwashing looks like. Equinor’s historic and projected energy sales. The green slither is renewables [click to enlarge]. Image: Ketan Joshi

Norway’s state-owned oil major Equinor escapes the scrutiny of more reviled rivals such as ExxonMobil, Shell and Chevron because of its widely publicised efforts to transition to clean energy. The company announced a 2050 net-zero target in November 2020, committing to align with the Paris Agreement as it looks to be a “leader in the energy transition,” according to chief executive, Anders Opedal. In the first quarter of 2021, almost half of the firm’s revenue came from selling off wind farm development projects. But also Q1 2021, of the total energy sold by Equinor, just 0.54 per cent was zero carbon, an opinion piece by science writer Ketan Joshi pointed out. As Gurīn Energy boss Assaad Razzouk tweeted, Equinor deserves a net-zero greenwashing prize.

Have we missed any? Let us know by writing to news@eco-business.com. This story is part of our Year in Review series, which journals the stories that shaped the world of sustainability in 2021.

A section in the story about the Asia Corporate Excellence & Sustainability (ACES) Awards has been removed. Eco-Business had reached out to the company for comment but did not receive a response prior to the original article date. We have since received clarification from the company that winners of the ACES Awards are selected after a nomination process that goes through various stages and includes a final decision made by a panel of judges. Winners have the option to then subscribe to a platform to promote their accolades and such a decision to subscribe is made after the winners are announced and is not a condition for winning an award. Thus, we apologise for any misreporting on our part.