Sex can be a messy, noisy, dirty business. But it doesn’t have to screw the planet.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In fact, from finding a partner to choosing environmentally-friendly bedroom paraphernalia, sustainable sex may be something of a lifestyle trend, say experts.

Couples have been coming together through a shared passion for the environment in the West for more than 20 years, meeting through green-themed dating sites such as the United States’ GreenSingles.com and ConcernedSingles.com.

Now, ecosexuality—that is, the trend of people who lead environmentally-conscious sex lives (not to be confused with people who actually believe that having sex with Mother Nature will save the planet)—is showing signs of growth in Asia too.

Ecosexuals, says Singapore-based sexologist Dr Martha Lee, are most likely to be vegetarians or into the organic movement, and tend to be searching for a partner who feels as strongly about sustainability as they do.

“

Talking about sex is taboo in Asia. If eco advocates want sex to be part of the sustainable lifestyle trend, they need to take the lead in conversations that help bring sex more out into the open, to make it normal.

Erin Chen, sex and wellness counsellor

They’re most likely city dwellers who recycle, cycle, eat locally-produced food, avoid air travel and have an aversion to plastic packaging, she says.

Lee, who has published a video series on ecosex, adds: “They want to make a difference in the world through their lifestyles. They believe that doing something, starting with themselves, is better than doing nothing.”

But is it realistic to think that people are thinking about the environment when they’re ripping each other’s clothes off? Sustainability just isn’t sexy—or is it?

Eco sexuality is a thing—but not in Asia yet, says sex and wellness counsellor Erin Chen.

Erin Chen, a sex and wellness counsellor, is not convinced that eco-sexuality holds much currency in Asia, even though she co-staged her sex lifestyle event Spark with green living event Green Is The New Black in Singapore last year.

“Ecosexuality is a thing if you google it; there are articles on it. But I’m not sure there’s such a thing as sustainable sex in Asia yet,” she says.

Where sustainability has started to creep into conservations about sex is the topic of sexual wellness comes from a growing concern for sexual wellness—that is, the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of people who enjoy sex in their own time and on their own terms.

How to be an ecosexual—in 7 simple steps

1. Don’t have kids

2. Wear a vegan condom

3. Use petroleum-free lubricant

4. Watch vegetarian porn on a Vivaldi web browser

5. Use a sheathed cucumber as a sex toy

6. Say no to sex robots

7. Be nice to sex workers

This has meant that people, particularly women, are more likely to choose, say, an organic lubricant over a synthetic variety, or a glass dildo rather than a silicone one, because it is safer, not necessarily because they want to save the planet while getting off, she says.

Meika Hollender, co-founder and co-chief executive of Sustain Natural, a company that makes vegan, organic and Fairtrade condoms, lubricant and wipes, agrees: “To me ‘going green’ in the sex context is about women beginning to reconsider everything they use, just as they are in other aspects of their health and wellness routine.”

“Just as we are taught to avoid things like glycerin and parabens in our skincare products, the same applies to things like lubricant,” she tells Eco-Business. “Your vagina is one of the most absorbent parts of your body, so it’s important to think about what’s going inside it,” she adds.

Growing demand for safer, more natural products has meant that Hollender’s business has seen “exponential growth,” she says.

The sexual wellness market—which involves products such as sex toys, contraceptives and lubricants—is predicted to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 6 per cent globally between 2017 and 2022, and is expected to eclipse US$37 billion over the next four years, according to data from business intelligence firm Arizton.

This growth is driven by Asia Pacific, the research shows. Surging demand, mainly for condoms but also for sex toys, is being driven mainly by the Chinese, Indian, and Japanese markets.

But there are natural barriers to the growth of sexual wellness that could put a cap on the rise of ecosexuality, particularly in a region as culturally conservative as Asia, says Chen.

“Talking about sex is taboo in Asia,” she says. “If environmental advocates want sex to be part of the sustainable lifestyle trend, they need to take the lead in conversations that help bring sex more out into the open, to make it normal,” she says.

With this in mind, Eco-Business’s special report explores how we can make our sex lives better for both people and the planet.

Children in Medan, Indonesia, where the population has grown by 10 million in four years. Image: Eco-Business

Birth control

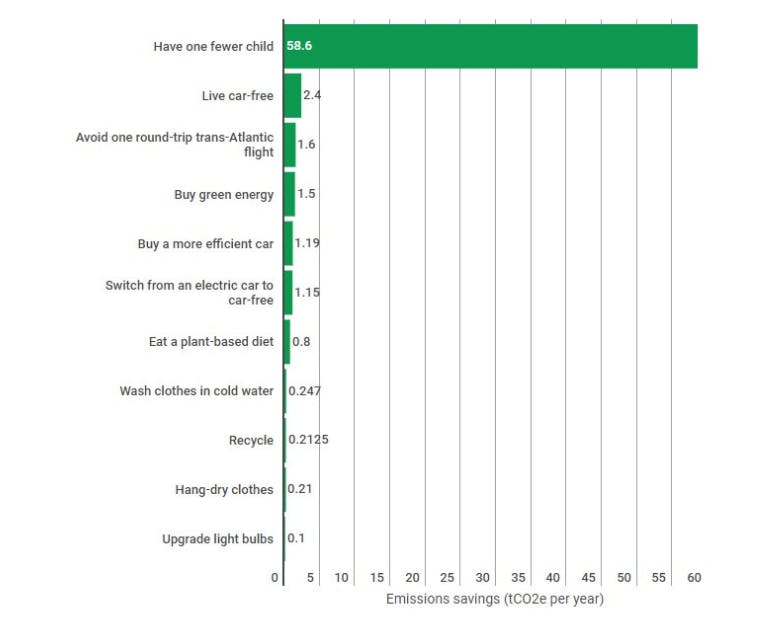

It might not be a politically correct thing to say, but unless your child turns out to be Al Gore, Naomi Klein or Vandana Shiva, not having a child is one of the kindest things you could do for the planet in your lifetime.

If you are a GINK (Green Inclinations, No Kids) in a rich, developed country, your environmental impact will be 20 times lower than if you adopted the most eco-friendly practices possible, like using energy-efficient appliances and recycling, for all of your life, according to a study by Oregon State University.

The best way to reduce your carbon footprint is to have one less child. Data: Wynes & Nicholas, Environmental Research Letters

The key to this, of course, is contraception. But unfortunately, the technique with the lowest environmental footprint—the withdrawal method—is also the least effective. Assuming that the man pulls out at exactly the right time, couples who use this method are 85 per cent likely to get pregnant within a year, and the technique offers zero defence against sexually transmitted diseases.

When it comes to physical or hormonal methods to prevent pregnancy, the two most common methods are condoms and contraceptive pills. Both are far better at beating pregnancy and in the case of condoms, venereal illness, than the withdrawal method. But neither are particularly green.

The estrogen in pills is washing into waterways through women’s urine and turning male fish into female fish, which upsets aquatic ecosystems. And condoms, which are typically made of latex rubber or polyurethane with hardening agents so they can withstand friction, and come in wrappers made of plastic or treated foil, are piling up in landfills or are being burned in garbage incinerators.

Around 11 billion condoms are made every year. The most common type, made from latex rubber, takes between six months to four years to decompose, depending on which preservative chemicals the material has been treated with. Condoms made of polyurethane, a type of plastic, take a lot longer.

Though the main driver of growth of the rubber trade is massive demand for tyres, particularly from China and India, condoms play their part in the expansion of an industry linked to the disappearance of rainforests in Malaysia, Indonesia, China, Vietnam and Thailand.

Not only do rubber plantations replace carbon-rich rainforests that are home to endangered species such as tigers, rhinoceros and elephants, rubber processing consumes huge quantities of water and energy, and the chemicals used to process it, which include sulphuric acid to soften the latex, are highly polluting to waterways.

The footprint of condoms is not limited to their environmental impact. Though they cost around 10 cents to make, and sell for between 60 cents and two dollars each depending on the country, plantation workers and rubber tappers often work in hazardous conditions.

Workers barely live above the poverty line and local communities that depend on rubber often suffer from malnutrition, a problem exacerbated by the chronically low price of the commodity.

The greenest sort of rubber johnnies aren’t made of rubber at all. Trojan Condoms’ Naturalamb brand is made from sheep intestines, which is completely biodegradable and supposedly feels warmer and more natural than the latex variety. However, they also cost about three times as much as regular ones and provide little protection against STIs, as the sheepskin has pores.

An advertising campaign for Sustain Natural condoms. Image: Sustain Natural

For those who don’t want animal parts in condoms, there’s Sustain Natural’s vegan condoms. These use fair trade rubber, do not contain casein, a milk protein commonly found in latex condoms, and are processed in solar-powered factories.

The condoms also do not contain nitrosamines, a chemical which is potentially cancer-causing in large doses. Oh, and 10 per cent of the New York-based company’s profits go towards women’s healthcare charities.

There are also several other vegan condom makers: rival brand Glyde, of Australia, Sir Richard’s Condoms, which for every condom sold donates one to a developing country, L Condoms, Unique Condoms, Lifestyles Skyn and Avanti Bare RealFeel, a sub brand of Durex.

The birth-control option that strikes the best balance between effectiveness and sustainability for women is also physical—the intrauterine device (IUD), a small, t-shaped device that is inserted into the uterus.

Though they offer no defence against STIs, they are much better at baby-stopping than the pill, with prevention effectiveness of 99.2-99.8 per cent. However, IUDs are not perfect, and have been known to cause mood swings, bleeding and damage to the uterine wall, these devices use few resources and can be worn for up to five years before being re-fitted, depending on the type you use.

For men, a very green way to prevent a pregnancy, but also offering no protection against diseases, is to get a vasectomy (or tubal ligation, or “the snip”). They’re also reversable, if the couple has a change of heart.

Like most things these days, when it comes to preventing unwanted babies, there’s an app for that. Natural Cycles, an app developed by a couple of Swedish physicists, claims to be about as effective as the pill and takes away the need for any physical or chemical interference—you just need a good memory and a bit of motivation.

The Natural Cycles app. Image: Natural Cycles

Though it works using the same basic principle as an invention that came about in the 16th century—the humble calendar—Natural Cycles is based on an algorithm that uses body temperature—which rises at the point of ovulation—and the time since your last period to work out when it’s safe to have unprotected sex, and when it isn’t.

Though the app may not be suitable for everyone, as it requires a lot of commitment and diligent measurement taking, only seven out of 100 women who use the app will unintentionally get pregnant versus nine out of 100 taking the pill, according to the firm’s own study (other studies find fertility awareness apps have a much higher failure rate of about 24 pregnancies out of 100 women). It’s also the world’s only app to receive government approval as a method of contraception.

Of course, Natural Cycles provides zero protection against STIs. But beyond the meagre amount of power needed to run the app, it is among the greenest contraceptive options.

Toys & lube

For the most environmentally friendly sex toy there is, look no further than your own backyard or the produce aisle in your local supermarket.

The humble carrot, cucumber or eggplant might just be the best possible way for people to get off without damaging themselves or the planet.

Vegetables are free from the harmful ingredients used to make petroleum-derived plastic sex toys, such as phthalates, a chemical used to soften plastic.

But the snag is that their skins also harbour bacteria, so they should be used with a condom, advises Dr Lee.

But since fruit and vegetables don’t last forever, and using food as a toy is wasteful unless it’s eaten afterwards, what’s the most sustainable alternative? Try wood sourced from sustainably-managed forests, Lee suggests.

While wood might seem like a risky option (splinters!?), treated wooden toys are splinter-proof, water-proof and hypoallergenic as well as organic, natural feeling and rather beautiful to look at, she points out. Try this range from Oregon-based Hans Hardwoods, handmade from scrap wood salvaged from lumber yards, trimmed or fallen trees, or given to him by friends.

Glass, another material that might seem risky to repeatedly thrust inside our bodies, is also a much greener option than the more popular synthetic varieties, says Lee.

The Solar Bullet vibrator, powered by the sun. Image: Pyramidcollection.com

Glass sex toys are made from tempered, shatter-proof medical-grade glass, which is non-toxic and phthalate-free. Why not give the self-described “glass dildos of distinction,” a go from The Glass Dildo Shop?

Glass and wood are far more durable than plastic, silicone or rubber sex toys, which start to break down, smell funny, look weird, and lose their freshness after a while.

For toys that buzz, why not try some sun-powered fun—like the Solar Bullet?

If you’re going to use a toy that’s more easily available on the mass market, at least use one that is rechargeable and doesn’t need disposable batteries.

For lube, go for a natural or water-based one that is vegan, as well as paraben, petroleum and glycerin-free, says Lee.

Parabens are a type of preservative used to prolong the shelf-life of lubricants, and it prevents the growth of bacteria and fungi. But recent studies have linked paraben, which disrupts hormone production in women, to cancer.

For natural, guilt-free lube, Dr Lee recommends Good Clean Love, Sliquid, Vie Super Slick, Blossom Organics and Intimate Organics.

“

If we watch a film about superheroes, we realise that we’re not Superman or Superwoman. If we watch a Bollywood film, we know that people don’t burst into song and dance on the streets. But we don’t have that reality check with porn.

Erin Chen, sex and wellness counsellor

Pornography

Pornography is a bit like palm oil. Everyone consumes it, without really understanding how destructive the industry behind it is.

A quirk of the adult entertainment business is that it is one of the few industries in which women are better paid than men. But the reality is that the business still pays pretty poorly, and wages are under constant pressure due to the proliferation of free porn on the internet.

Though hard data on what is believed to be a multi-billion dollar industry is hard to come by, a “typical” sex scene between a man and a woman pays an average actress between US$800 and US$1,000 depending on the budget of the production company, according to a study of mostly porn stars by American TV company CNBC last year. Newcomers can earn as little as US$300 for a scene, if they are poorly represented by weak agents.

Unless the performers are mega stars who can earn up to $2,000 for a scene, wages level off or fall over time, unless actors perform new sex acts that they have not done before. More extreme sex acts, which may be uncomfortable, painful, or demeaning, pay better.

A video on Bike Smut, a site for people who are turned on by bikes and their riders. Image: Bike Smut

The more extreme the content, the less realistic it is likely to be. Most mainstream porn is made for male gratification, and does not provide young men or women with sound sexual roles models, says Spark’s Erin Chen.

“If we watch a film about superheroes, we realise that we’re not Superman or Superwoman. If we watch a Bollywood film, we know that people don’t burst into song and dance on the streets. But we don’t have that reality check with porn,” she says.

Research on the effects of porn on adults is inconclusive. A number of studies have suggested that the widespread availability of saucy material online may lead to a decrease in rape and other sexually violent behaviour, even child sex abuse.

Other suggest that a higher rate of porn-watching among men leads to a greater appreciation for gender equality and women’s rights; porn fans are more likely to believe that women can enjoy sex and do it for reasons other than pleasing their partners or having children.

However, other studies link chronic porn consumption to a breakdown in normal relationships within couples, an increase in promiscuity, and a decline in desire to start a family. Watching lots of porn might also, quite literally, cause your brain to shrink.

The most damaging thing about porn is the effect that it has on people too young to be watching it—for instance, it could encourage risky behaviour, such as unprotected sex or underage sex. However, this research is also considered to be unreliable, because of sensitivities around studying children watching porn.

Chen, whose Spark event series aims to de-stigmatise sex by getting people to talk about it, points out that there are alternatives to mainstream porn that provide a better way for young people to learn about sex, and are less exploitative.

Ethical pornography, also known as “fair trade” porn, is typically made by women for women, though not exclusively.

The sex acts performed in ‘ethical porn’ films are negotiated consensually by the actors, who are fairly paid. The material wouldn’t necessarily look out of place on a mainstream porn site, but is made with the guiding principle of respect for all involved.

Though very niche, there’s a lot of variety: female-perspective porn, such as Bright Desire, founded by an Australian former librarian; Veg Porn, made by vegetarians for vegetarians; Fuck For Forest, which features nature-lovers frolicking in forests; Bike Smut, a sex site for cyclists; and Audio porn for the visually impaired.

Another outlet for guilt-free porn consumption is a subscription website founded by British fifty-something Cindy Gallop, an advertising executive turned ethical porn evangelist.

In interviews and at events such as ideas fest Ted X, Gallop has observed that many of her young lovers want to ejaculate in her face. Suspecting that they had learned that behaviour to be the norm from hardcore porn, she started MakeLoveNotPorn.com in 2009, a user generated site featuring regular, loving couples having what Gallop refers to as “real world sex”.

For porn that teaches as well as titillates, the films of Swedish filmmaker Erika Lust, a leading light in feminist erotica, are worth watching, with well cast actors and high production standards.

Though the environment probably ranks low on the list of your priorities while spanking the monkey or strumming the banjo, ecosexuals might want to try switching browsers to lower their carbon footprint.

Vivaldi, a browser founded by Norwegian computer programmer Jon von Tetzchner locates its servers in Iceland, the only country in the world to have an electricity supply that is fully powered by renewable energy.

If you’re not into porn, you might want to use Ecosia as a search engine for all your web-surfing needs anyway. The site does not serve any searches for porn, and with every search on Ecosia, money goes towards a tree planting scheme.

“

People think [sex work] is all wham, bam, thank you, ma’am. But the reality is that is usually the smallest part of a session with a client.

Rachel Wotton, sex worker

Paying for sex

Paying for sex is taboo pretty much wherever you go. But a short walk through Bogyoke market in Yangon, Nana in Bangkok, Street 136 in Phnom Penh, Geylang in Singapore or King’s Cross in Sydney is enough to convince anyone that the world’s oldest profession is still doing a roaring trade across the region.

But is it possible for pay for sex in an ethical, respectful manner? Or is it inherently exploitative, and therefore unsustainable?

Yes, it is possible, says Sherry Sherqueshaa, a transgender sex worker in Singapore, but only if the sex worker is treated with respect—and that starts with the name we give their job.

“Stop calling sex workers prostitutes,” she says, because the term prostitution implies that sex workers are forced into the job, and that is not always true.

Sherry Sherqueshaa, a volunteer for sex worker rights charity Project X. Image: Sherry Sherqueshaa

Transsexuals in Singapore are stigmatised and find it hard to get a regular job, so they—like Sherqueshaa, who dropped out of school while she was transitioning—go into sex work of their own volition.

The Singaporean, who has been in the trade for the past six years, says that while there certainly are sex workers in Singapore who have been exploited, about one fifth of her peers do the job because they have chosen to; some are single parents who like the flexibility of sex work, others do so because they can earn a living from a pursuit they actually enjoy.

“We are not just people who are obligated to cater to your sexual needs,” says Sherqueshaa, who volunteers for Project X, a group that campaigns for the fair treatment of Singapore’s sex workers.

“It should be a fair trade; I’m a provider, you’re the receiver. On that basis, we should have mutual respect for one another. We should be treated like anyone who provides a service,” she says.

Greater respect for sex workers would mean a safer working environment for them, she believes.

Even in Singapore, where regulated sex work comes with certain protections such as regular health checks and the security of working in a licensed brothel, sex workers can face harassment, intimidation and violence, says Sherqueshaa.

Unlicenced sex workers, the majority of whom come from overseas and work independently on the street, are more vulnerable, although they can earn more as they’re less likely to kickback to a pimp or contribute to rent at a brothel.

“Whatever you earn is yours, but then you are putting yourself at greater risk,” she says.

One of the biggest risks is infection, and Singapore’s mandatory health checks for sex workers have created an illusion that commercial sex in the city-state is disease-free.

“Clients still ask me for unprotected sex. They tell me that they know I’m safe as I go for testing, so it would be okay to not use protection,” says Sherqueshaa, who shares that some clients have tried removing the condom during sex.

One of the most common forms of abuse is financial, says Sherqueshaa, who has experience of customers running off without paying after she’s provided a service.

But Singapore is a better place to work than Bangkok, one sex worker who works in both cities tells Eco-Business.

26 year-old transgender sex worker “Pip”, who works in Sukhumvit Soi 4 in Bangkok and Orchard Towers in Singapore, says she prefers to work in Singapore because she earns fives as much per trick, and it’s safer.

“We just want to be treated like people—not objects,” she says.

For some it is hard to justify paying for sex on any ethical grounds. But for some sex workers it is not just a job, it is a calling.

Rachel Wotton, an Australian psychology graduate turned sex worker with more than 20 years experience, believes that sex is a basic human right, and counts people with mental and physical disabilities among her clients.

“People think [sex work] is all wham, bam, thank you, ma’am. But the reality is that is usually the smallest part of a session with a client.” Providing counselling and emotional support is part of the job too, she says.

Some clients go to her before doctors for advice on sexually transmitted diseases because she knows as well as anyone what an STD looks like.

When you’re naked, you’re vulnerable, and part of the job is reassuring people about their bodies, she says.

“I love scars and the differences with our bodies, and I always notice that guys will hide parts of their bodies, and I’ll say, that’s a really interesting scar, tell me about it.

“There’s a story behind it. There’s pain and there’s survival,” she says.

Harmony, the world’s first sex robot with artificial intelligence. Image: YouTube/San Diego Tribune

Sex robots

Some people think that sex robots are a guilt-free alternative to having sex with sex workers. But just how sustainable is an android sex doll that knows what turns you on?

Life-size silicone sex robots are available to buy now, and cost between US$4,500 to US$55,000, depending on the level of customisation. They can smile, tell jokes, know how often you like to have sex as well as your favourite position, and can even orgasm—known as a “robogasm”—if touched often enough in the right places.

Some even have personalities that get to know the owner’s desires more deeply over time, thanks to artificial intelligence (AI). So far, the industry has focused on making female sex bots, but AI-powered male varieties with bionic penises are set to go on sale this year.

But effective as they may be, robots are hugely energy-hungry and require a lot of materials to make, and therefore are a huge drain on resources. They are also ethically questionable.

The pro-sex bot camp, which includes their creators such as San Diego-based Realbotix, the maker of Harmony, the world’s first AI sex robot, argue that robots are good for society by giving people a sex life they, for whatever reason, had been deprived of. Las Vegas-based engineer Roberto Cardenas even claimed in a filmed interview with the Guardian that sex robots help prevent rape.

But these views are deeply troubling for some. Dr Kathleen Richardson, of the United Kingdom’s De Montfort University, who founded the Campaign Against Sex Robots, thinks sex bots promote mysogyny and objectify women.

Sex bots are not just realistic sex aids, they’re models of subservient women programmed to obey, flatter and titillate. The danger is that their owners will come to expect the same of women in the real world, she believes.

Another predicted outcome of the rise of sex bots is that they’ll put sex workers out of work. But this idea overlooks one of the main reasons people pay for sex.

As Shannon Jennings, manager of the Sex Industry Network in South Australia, put it in an interview with The Guardian: “Seeing sex workers is about more than penetrative sex — clients want to be held and touched. If sex toys could replace human intimacy, I’d have traded my husband in years ago for a Sybian.”

Additional reporting by David Choy, Tan Jing Ling and Boo Yi Lin