Education levels and life expectancies remain sharply divided globally, as the world headcount looks set to reach the eight billion people mark in November, according to the latest United Nations (UN) projection.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Over half of the population increase up to 2050 – when the count is expected to hit 9.7 billion – will take place in eight developing countries, data from the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs showed.

Three of them – India, Pakistan and the Philippines – are in Asia. The other five – the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Tanzania – are in Africa.

Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa will see their population double by 2050, straining resources and challenging policies aimed at reducing poverty and inequality, the UN report added.

“Reaching a global population of eight billion is a numerical landmark, but our focus must always be on people,” said United Nations secretary-general António Guterres at the launch of the population report.

“It is a reminder of our shared responsibility to care for our planet and a moment to reflect on where we still fall short of our commitments to one another,” he said.

The world population last year stood at 7.8 billion people, according to the United States Census Bureau. The count crossed seven billion in 2011.

Disparities

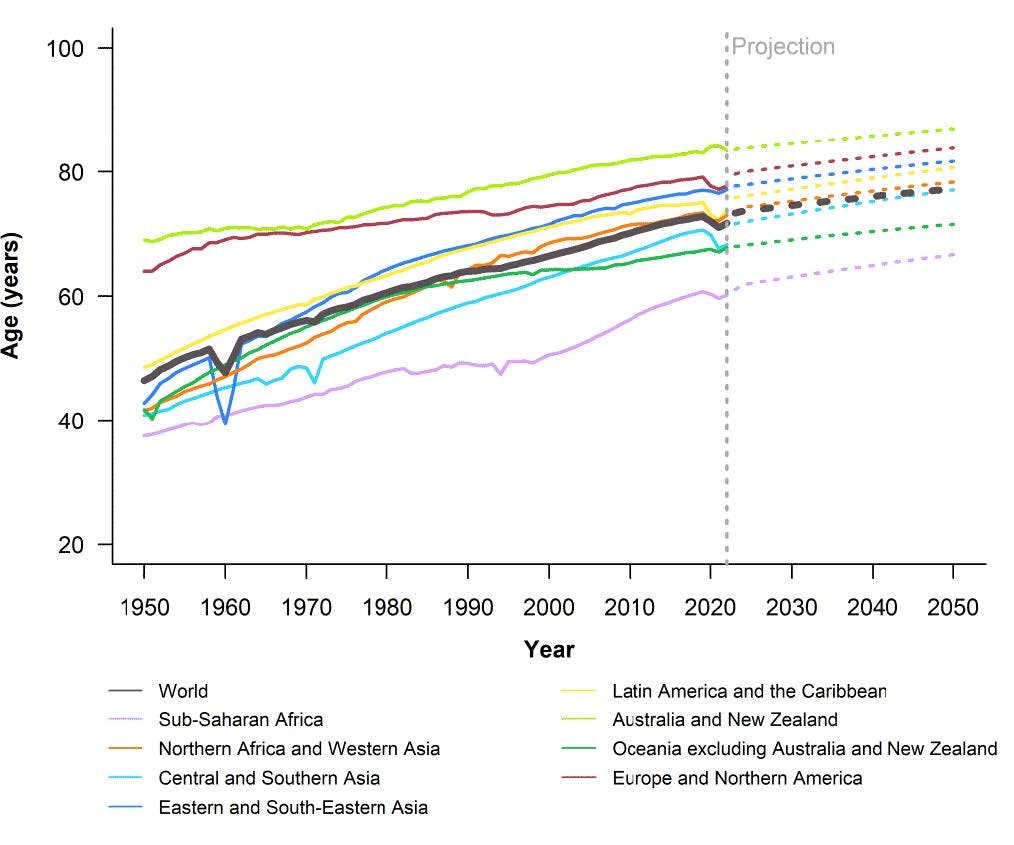

Estimates of life expectancy at birth by region. Image: UN DESA. [click to enlarge]

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the region with the lowest life expectancy in the world, while Australia and New Zealand continue to top the charts. These trends have held fast since the 1950s.

A child born in sub-Saharan Africa today is only expected to live until 60 years old, compared to 84 years in Australia or New Zealand. The gap has narrowed from about 30 years in 1950, but will still be around 20 years in 2050.

A child in sub-Saharan Africa is also 20 times more likely to die before reaching five years of age than a child in Australia and New Zealand.

The current world average life expectancy is about 72 years, and is expect to rise to 77 years in 2050.

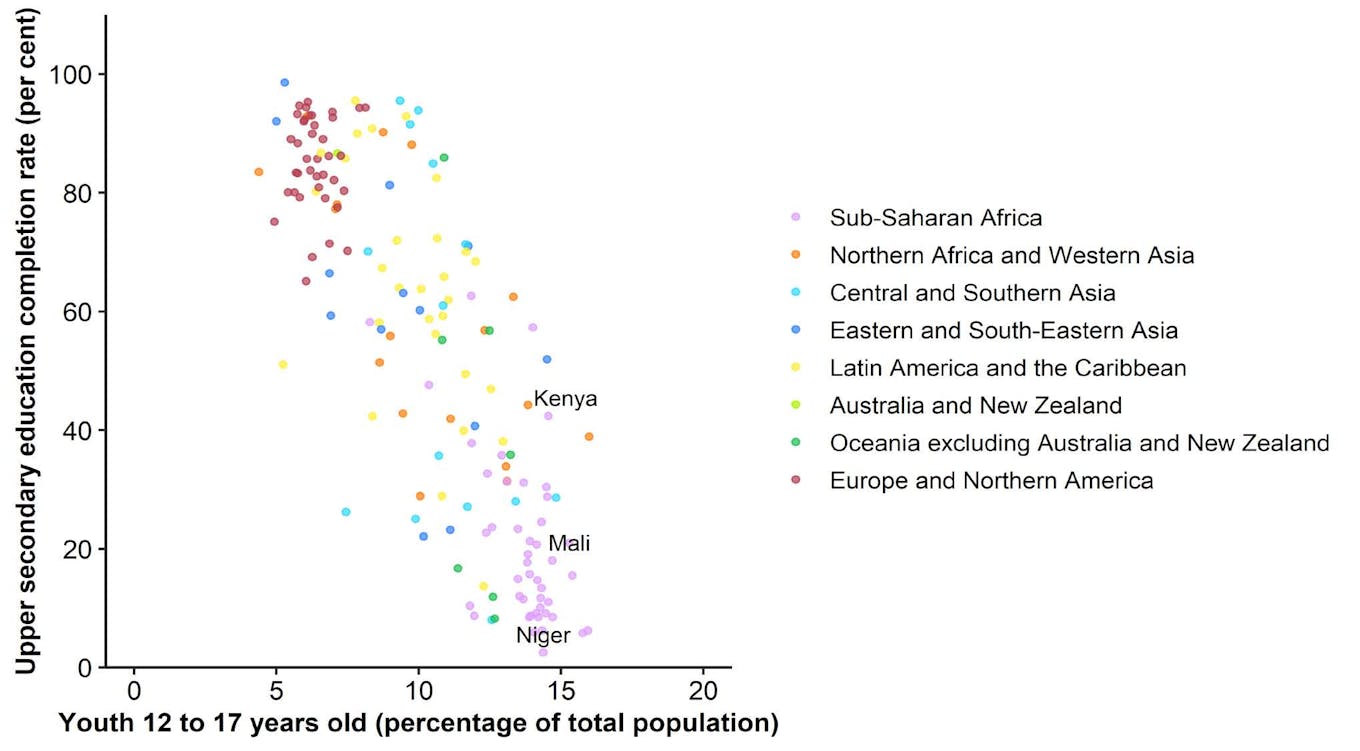

Upper secondary education completion rate for youths aged 12 to 17 years in 2021. Image: UN DESA.

Just over a quarter of children in sub-Saharan Africa completed upper secondary education, severely restricting the ability of youths to seek employment and improve their lives.

In Niger, a landlocked country facing chronic hunger and widespread terrorism, the figure was as low as 2.5 per cent.

Only Europe and North America have national secondary school graduation rates mostly above 70 per cent. Huge disparities exist in regions like Eastern and Southeast Asia, with national graduation rates ranging from 20 per cent to almost 100 per cent.

The UN report said the Covid-19 pandemic has taken away more education opportunities in lower income nations through school closures and lengthy sick days, further widening the privilege gap compared to richer countries. Covid-19 also caused a worldwide dip in life expectancy in 2020.

Prioritising education, healthcare and gender equality remain effective ways of lowering birth rate and giving people better lives, the UN report said.

Women in the least developed countries still bear an average of four children each, degrading the quality of support each child gets. Conversely, if working adults needed to feed fewer children, per-capita wealth would increase and economic development could speed up – a trend already seen in parts of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, the report added.

However, any additional efforts to slow population growth today will only manifest in 2050, as the trajectory in the coming decades has already been locked in by existing demographics and policies.

“

More developed countries — whose per capita consumption of material resources is generally the highest — bear the greatest responsibility for implementing strategies to decouple human economic activity from environmental degradation.

United Nations World Population Prospects 2022

Meanwhile, poorer small island states also have to contend with climate risks and sea-level rise.

“More developed countries — whose per capita consumption of material resources is generally the highest — bear the greatest responsibility for implementing strategies to decouple human economic activity from environmental degradation,” the report said.

India’s population to overtake China’s

The two most populous countries in the world will swap places next year, four years ahead of the previous UN projection in 2019. India’s population is currently just shy of 1.4 billion, while China’s is just over that figure.

China had imposed a strict policy to limit families to one child between 1980 and 2016, which quickly stabilised population growth but created concerns that the small youthful cohort will struggle to care for a large elderly population.

India, which does not have a national policy limiting childbirth, will have a “much smoother transition”, said John Wilmoth, director of the population division at the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

“In some ways that may be easier to manage in the long run, for the economy to have a more gradual demographic change than the very rapid change that has happened in China,” he added.

Globally, population growth fell below 1 per cent per year for the first time in 2020, continuing a downward trend since the 1960s.

The global headcount is expected to peak at 10.4 billion in the 2080s, down from the projection of 10.9 billion made in 2019.