Conservationists contend that the carbon offset market boom is prioritising the protection of high-carbon areas potentially at the cost of wildlife that lives in areas of lower carbon stock.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Areas siphoned off and preserved for their carbon value, risks displacing efforts to protect biodiversity. This troubles conservationists.

“Carbon has taken the focus away from preventing extinctions. When we think about tropical forests, we shouldn’t just be thinking of peat swamps, because of their high carbon value. We need to be thinking about the things that are living in them,” says Lahiru Wijedasa, Asia forest coordinator for BirdLife International, a conservation group.

Wijedasa, a botanist and forest restoration researcher who recently discovered a new species of flowering tree in a peat swamp in Sumatra, says that countless species are at risk of going extinct before they can be described.

“New species discoveries don’t get much attention anymore. And yet each species could be the building block of life we need to fight climate change. The last time proper ecological studies were done in peat swamps was in the 1960s. We’re losing sight of the value of the forests because of carbon,” he says.

Carbon market boom

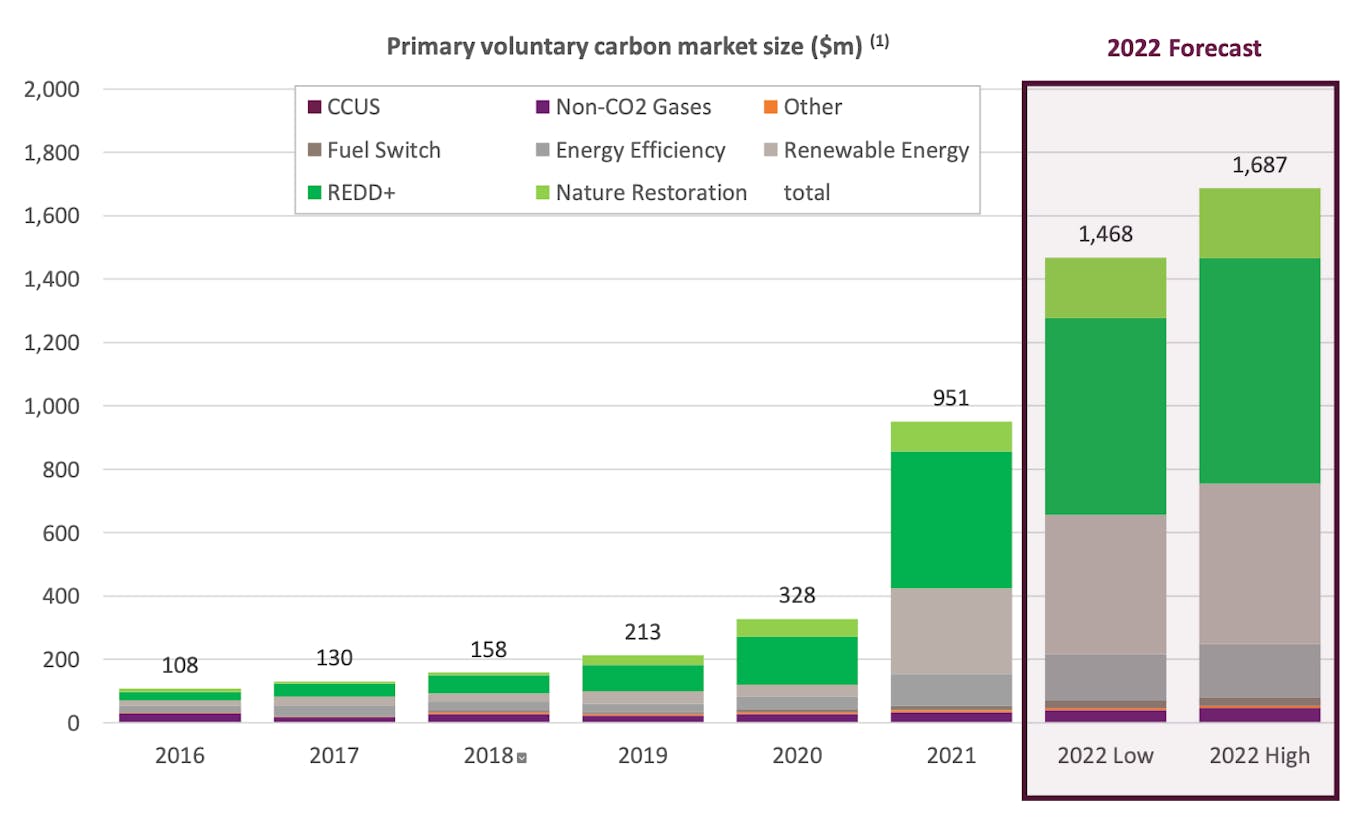

Money is pouring into carbon markets as governments and corporations race to offset their emissions to meet net-zero targets. The value of publicly traded carbon — that is, money polluters pay in carbon taxes — soared to US$851 billion in 2021, an increase of 164 per cent year on year. The global voluntary carbon market, which enables polluters to offset their emissions by buying carbon credits, grew by 190 per cent in 2021 to just under US$1 billion.

Meanwhile, spend on conservation, from both public and philanthropic sources, is US$5.2 billion globally. Conservation groups estimate that there is a US$700 billion annual deficit in funding that is needed to reverse biodiversity loss. Securing finance is a key part of the United Nations’ Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) negotiations currently taking place in Geneva, which aims to create a global framework to halt nature loss.

The flow of money into carbon started in the mid-2000s, around the time the film An Inconvenient Truth woke up the world to the impending doom of climate change, says Liming Qiao, Asia head of industry body Global Wind Energy Council, who previously led climate programmes for conservation group World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in China. “By 2007, the balance had tipped, and conservation money flowed into climate projects. To get funding for conservation projects now, there has to be a link to climate,” she says.

Keegan Eisenstadt, global head of nature-based solutions for South Pole, a climate solutions company, argues that conservation is benefiting from the growth in carbon funds. “The carbon market has actually enhanced the flow of capital into conservation. It’s just that now what was called traditional conservation has evolved into nature-based solutions programmes,” he says. Nature-based solutions are projects that protect and restore natural ecosystems, and benefit both people and biodiversity.

Eisenstadt’s team sources carbon projects that enhance degraded ecosystems or protect intact ecosystems. He notes that large conservation groups like Conservation International and Wildlife Conservation Society are all actively involved in forest carbon projects. These projects pour private capital into conservation that had previously been scarce, and enable non-governmental organisations to expand into new ecosystems that they didn’t traditionally work in, he says.

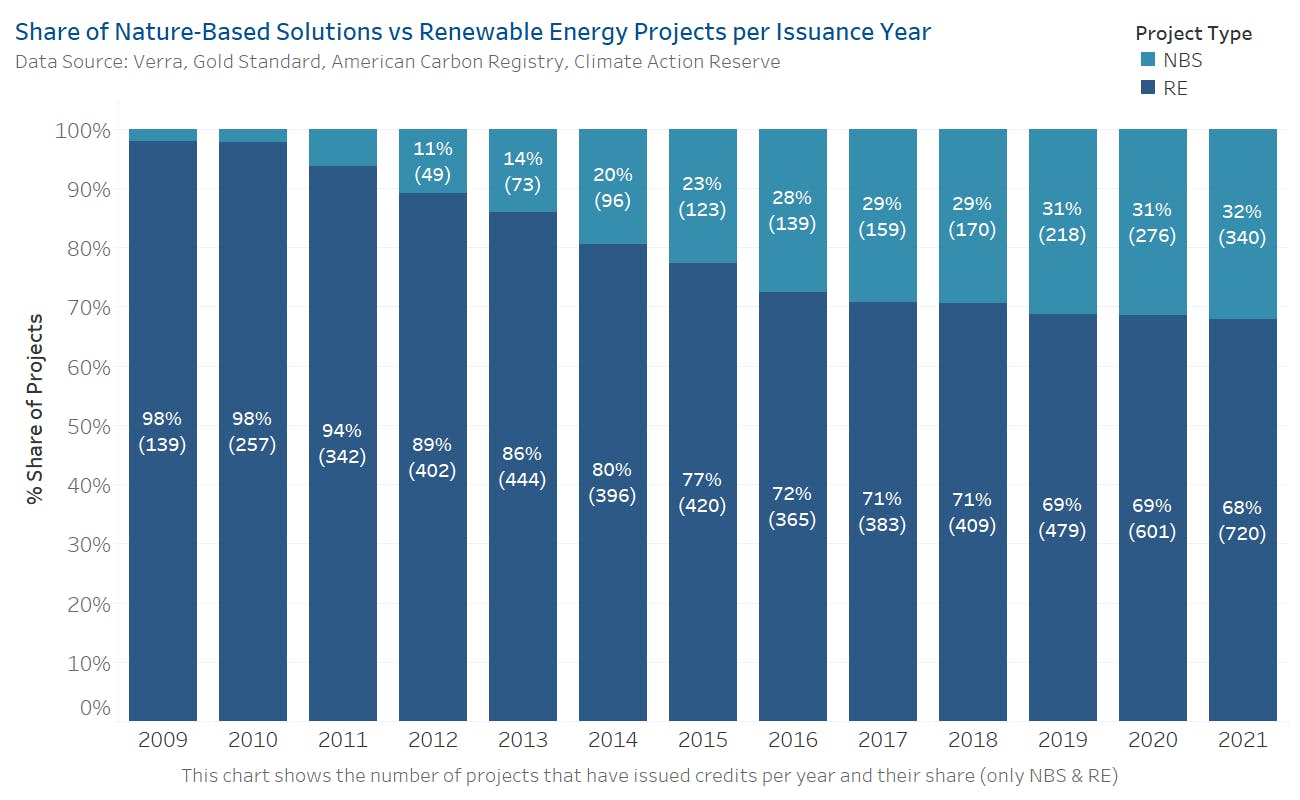

Nature-based solutions are an increasingly popular choice for companies buying carbon credits [click to enlarge]. Source: Verra, Gold Standards, American Carbon Registry, Climate Action Reserve

Evidence of this happening is the growing proportion of nature-based solutions used for carbon credits compared to other ways to offset carbon, such as renewable energy. In 2012, just 11 per cent of carbon credits were issued for nature-solutions. In 2021, the proportion had grown to 32 per cent, and Eisenstadt expects further growth.

Studies are emerging to show the potential benefits of conservation through carbon. Research by the National University of Singapore, published in February, found that if 58 per cent of threatened forest in Southeast Asia was protected by carbon projects, the dietary needs of more than 300,000 people a year could be supported by pollinator-dependent agriculture, and 25 million hectares of key biodiversity areas protected.

The study found that the higher the price of carbon, the bigger the potential benefits for people and biodiversity. “Investment in the protection of forests through carbon projects enables a financially viable and sustainable means of addressing other socio-economic and environmental issues beyond climate change,” the authors of the study wrote. Southeast Asia has the highest global concentration for carbon prospecting for investments in nature-based solutions.

Quantity rather than quality

But conservationists fret about the type of projects the money is flowing into. Recent figures for voluntary carbon market growth show that the majority of cash is being funnelled to REDD+, a United Nations’ scheme launched in 2017 that gives developing countries financial incentives to keep forests standing to absorb planet-warming emissions.

Among the criticisms of REDD+ is that it has not slowed deforestation, some projects do not reduce emissions permanently, while others worry Indigenous groups will lose control of their lands.

Most of the funds going into carbon are funnelling into REDD+ and renewables. A smaller proportion of carbon money is being spent on nature restoration. Source: Trove Research

A multi-million dollar carbon trading agreement signed in Malaysia in October aggrieved Indigenous groups who say they were not consulted about a deal covering two million hectares of Sabah forest reserves where they have lived for centuries. Profits are to be shared between the Sabah state government and Singapore-registered company Hoch Standard Pte Ltd. Local communities are excluded.

Including Indigenous people in deals to preserve natural areas is vital, as they are proven to be effective stewards of the land, according to the ICCA Consortium, a group that advocates for Indigenous and community-led conservation. Ensuring they are included in decisions about how land is conserved is a key consideration for the framework to protect biodiversity now being negotiated at the CBD.

“There is so much money, and the market [for carbon] is moving so fast — this is not conducive to consulting with indigenous communities, who rarely see the benefits,” says Brian O’Donnell, director of Campaign for Nature, a coalition of conservation groups pushing for at least 30 per cent of the land and sea to be conserved by 2030.

O’Donnell, who is involved in the negotiations in Geneva, says that carbon markets value a tree for how much carbon it pulls out of the air, rather than as a habitat or provider of clean soil, water and air. But not all trees planted to lock-in carbon benefit biodiversity, he says.

In the Western Ghats in India, monoculture plantations of non-native trees make poor habitats for local wildlife, and are less reliable at storing carbon than more diverse native forests. In some areas, carbon credits schemes have planted trees on grasslands, removing a habitat for wildlife adapted to life on the plains.

A native forests (right) stands opposite a monoculture teak plantations (left) in a protected area of the Western Ghats, India. Conservationists say native forests are more reliable at sequestering carbon than planted forests. Image: conservationindia.org

There are positive case studies, too. Through the sale of REDD+ credits, conservation group Wildlife Alliance has been able to fund its work protecting Cambodia’s Cardamom rainforest. The project, which gives fully-equipped wildlife rangers a decent wage as well as full health and life insurance, ensures that 8,347 square kilometres of forest is patrolled and protected, and 15 villages across the landscape benefit too, from ecotourism. The project prevents more than 3 million tonnes of carbon emissions annually.

Professor Koh Lian Pin, director of the NUS Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions, says that nature-based carbon projects may have risks, but they also present “genuinely virtuous opportunities” to turn off one tap of carbon emissions while conserving natural ecosystems, people and wildlife.

Climate change and biodiversity — two sides of the same coin

But more mutually beneficial projects where both carbon and biodiversity conservation can be achieved are needed, argues O’Donnell. He points to Costa Rica in Central America where a carbon tax pays for the country’s conservation system, and Gabon in Central Africa where Norwegian oil and gas money is being used to keep the country’s forests intact.

Eisenstadt of South Pole says more work needs to go into coupling climate and conservation finance, so that investments protect areas of lower carbon where there is high biodiversity. Biodiversity credits, which enable governments and firms to compensate for their impact on nature, are still in their infancy, as putting a price on a nature is not easy.

Currently, nature-based solutions work on the principle that local biodiversity and local communities benefit, and the co-dependence of people and nature are clear in the form of jobs, water and food securty, and resilience against natural disasters.

Eisenstadt concedes that the carbon market is not going to alleviate nature loss on its own. “The carbon market is a stop-gap for the transition off fossil fuels. If the carbon market is still the main driver for greenhouse gas mitigation in 50 years, I think we have missed the boat,” he says.

Hitting the 2030 targets set in the Paris climate accord depends to a large extent on conservation — afforestation, reforestation and forest restoration could make up almost 18 per cent of emissions reductions needed to achieve the 1.5°C Paris target — so climate and biodiversity should not be treated as separate issues, adds O’Donnell. But companies and governments should not use nature-based solutions to avoid making necessary emissions reductions, he says.

“Climate scientists have shown nature’s ability to absorb carbon, but the idea that nature can do the work of offsetting emissions is a fallacy,” argues O’Donnell. “We have to protect natural areas and rein in emissions. Nature is not a get out of jail free card.”

This story has been edited, with new perspectives added in paragraphs 7 and 8 of the ‘Carbon market boom’ chapter, and paragraphs 8 and 9 in the ‘Quality rather than quantity’ section.