In many parts of the world, the labour movement is still getting to grips with the climate crisis. However, given that trade unions are key players at the policy negotiation table, the public increasingly want them to be clearer in stating their stance, or join as part of the climate movement.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Ahead of this year’s Singapore Climate Rally, the event’s youth organisers had highlighted the significance of getting a union representative to speak at the panel. Its list of speakers included K. Karthikeyan, the executive secretary of the United Workers Of Petroleum Industry (UWPI). The union represents about 4,000 Singapore fossil fuel workers in 35 firms, including the likes of BP, Chevron and the Singapore Petroleum Company.

In a four-minute address at the virtual event, the 62-year-old spoke about cutting emissions, supporting higher taxes, and his concern for job losses amid the green energy transition. He reminded the audience that fossil fuel derivatives are found almost everywhere, from drink cans to drugs.

“We are encouraging companies to slowly move into renewable energy,” he said, emphasising that this depends on whether the firms have the resources and money to invest in new technologies. He acknowledged that Singapore’s green policies are slow, primarily because the government wants to avoid major disruption to firms.

“The youngsters are the future of our generation, who are going to take over policies. So, it is good to know that they care for the environment,” Karthikeyan told Eco-Business of his experience attending the rally, a key event initiated by youth activists in Singapore, organised for the second time since 2019.

In parts of the Western world, trade unions are now seen as key players in climate action. They hold considerable sway at often feisty negotiating tables and sometimes use their clout to block green bills that are seen to hurt workers.

In Singapore, labour relations have been focused on collaboration between unions, government and firms, with the last organised strike occurring in 1986. But unions have shown to bare teeth when needed. Last year, a secret vote for industrial action was held amid COVID-19 retrenchments, forcing firms to provide better terms. In 2011, the UWPI, which Karthikeyan represents, got firms to stop cutting the pay of older workers.

Suraendher Kumarr, 27, a co-organiser of the climate rally, said it was a pleasant surprise that Karthikeyan came on board the rally. The UWPI represents a lot of different companies, so Kumarr thinks him articulating his stand is substantial and encouraging.

“It is good that fossil fuel workers themselves and the unions are not climate denialists, and that climate denialism as a whole has, I think, generally waned,” he said.

“

It’s good that fossil fuel workers themselves and the unions are not climate denialists, and that climate denialism as a whole has I think generally waned.

Suraendher Kumarr, Singapore climate rally co-organiser

Kumarr said the campaign’s stance in backing workers’ welfare helped get Karthikeyan on board. Earlier this year, the organisers petitioned against Singapore’s petrol tax hike, saying it hurt freelance drivers and delivery workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We do not want workers in the fossil fuel sector to be thrown under the bus and I think according to what Karthikeyan said, there is a consensus,” said Kumarr.

This month’s rally isn’t the first time the UWPI reckoned with climate change. In 2011, the union wrote in its newsletter about the need to develop sustainably and cut emissions after attending global union conferences.

But petrochemicals remains a key driver of Singapore’s economy. It hires some 27,000 workers, contributes to a fifth of industrial output and 3 per cent of GDP. Over 100 chemical firms operate in Singapore, making the country a global refining and trading hub.

The industry generates close to half of Singapore’s greenhouse gas emissions. The country is banking on new fuels, greater efficiency and carbon capture technology to keep the sector relevant. New facilities for recycling plastic waste and processing biomaterials are being developed, creating new jobs.

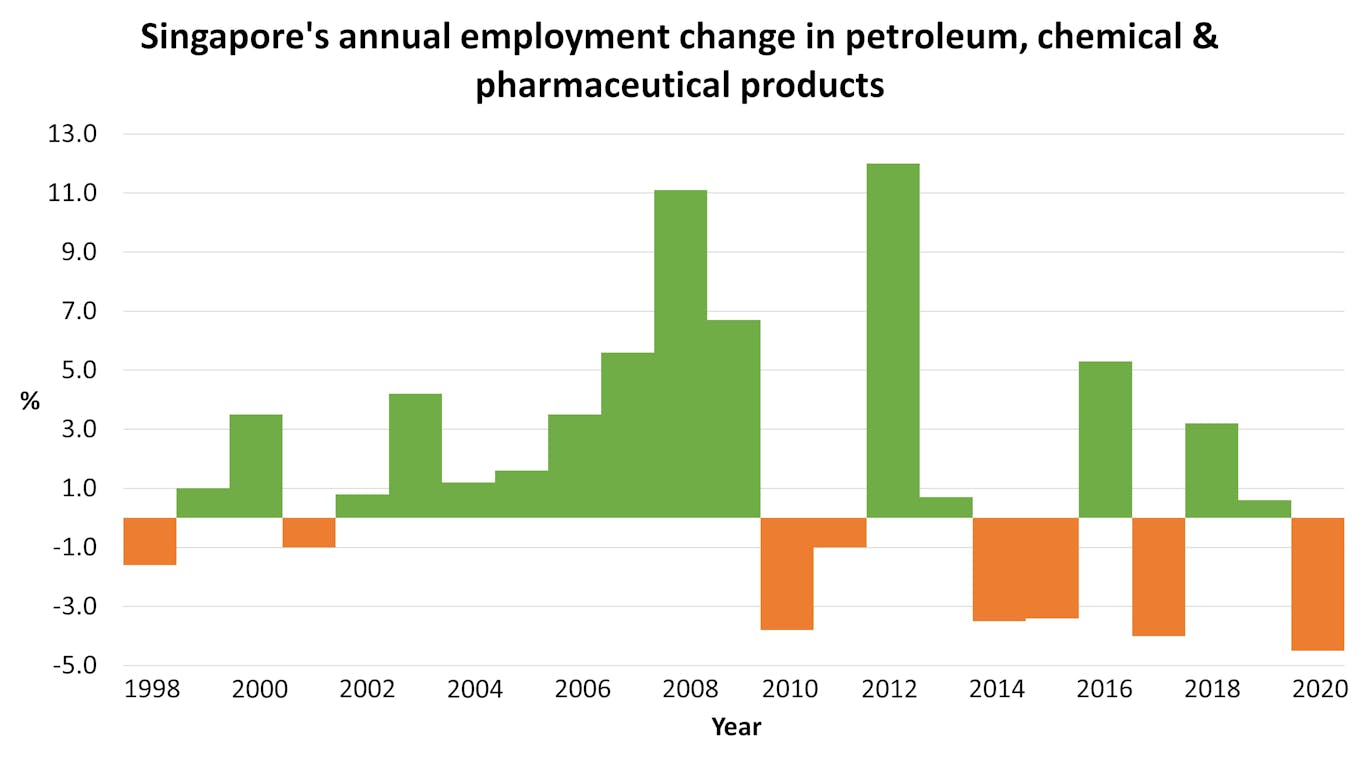

Still, existing jobs are starting to trickle away. Oil giants Shell and ExxonMobil, whose workers are not organised under UWPI, are cutting 800 positions from their Singapore operations. Worker numbers fell for five out of the last ten years in Singapore’s petroleum, chemical and pharmaceutical sectors, even though they’re still at some of the highest levels since the 1980s.

Data source: Singapore manpower ministry

Karthikeyan said firms under his union’s watch also have plans to move to cleaner businesses, but are afraid of telling their workers, lest they feel that their jobs are at stake. So UWPI has been prodding the workers to learn more skills and explore new industries, such as solar power.

Karthikeyan added that he wants firms to tell the union about future job cuts early, as helping workers find new careers could take years.

He is open to working with climate activists, and wants them to lead society in the shift away from plastic products - something he says would be unpalatable if he told the workers himself.

“It is supply and demand, pure economics. These are companies. When millions of people want plastic bags, they will produce,” Karthikeyan said.

On the climate activists’ side, Kumarr said he wishes to see unions listen to their workers more and include them in plans to go carbon-light.

“If we have a shared space to equally talk about things and have the workers there as well, that would be fair and equal collaboration. And maybe even have a little bit of healthy sort of criticism on both sides,” he said.

No ideal way forward but tie-ups gaining popularity

Globally, trade unions are warming up to climate activism. In 2019, some European Trade Union Confederation members marched with the Youth for Climate group in Brussels, joining a global wave of climate rallies run by young people.

“Everything we have been fighting for since our movement was born – social justice, workers’ rights, health and safety and decent wages for all – will be in danger if we don’t stop the climate crisis,” the union’s chief had told the demonstration.

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which represents 200 million workers, put it more bluntly in a 2014 campaign for unions to declare climate goals. The first page of its registration form read: “There are no jobs on a dead planet”.

But tie-ups between climate activists and unions specifically in the fossil fuel industry remains uncommon, according to Samantha Smith, director of the Just Transition Centre at ITUC.

“That was an outlier,” said Smith of Karthikeyan’s appearance in Singapore’s climate rally. She added that such tie-ups are not a guarantee for the best outcomes.

“In some countries, there’s so much conflict between climate activists, the government, the employers, sometimes also the unions, that the best role for climate activists is actually not trying to be part of the process, but pushing on the process from the outside,” Smith said, pointing to Poland as an example.

The country’s government and traditionally stubborn miners’ unions agreed in April to phase out coal production by 2049, a feat Smith attributed to pressure from Polish and European activists.

Climate activists and unions remain at loggerheads in other countries too — such as over oil and gas pipelines in the United States, and natural gas facilities in Australia.

But that is set to change, according to Smith, as the fossil fuel sector gradually comes to terms with inevitable changes. She thinks more unions may seek alliances with the climate movement, or use complementary strategies.

Some of them are starting to accept the need for a “just transition” into clean energy, where workers’ livelihoods are protected as communities ditch fossil fuels. Norway’s Electrician and IT Workers’ Union, which has people in both the fossil fuel and clean energy sectors, had shifted from calling for more oil drilling in the early 2010s, to ditching oil exploration and creating greener jobs by 2017.

In California, two unions covering thousands of fossil fuel workers joined others this year to endorse a 2045 net-zero plan that aims to provide pension and re-employment guarantees to laid-off fossil fuel workers. The proposal claims to be able to do that with just 0.02 per cent of the state’s gross domestic product each year.

In Singapore, the climate rally organisers want to be part of the conversation on protecting fossil fuel workers amid the green shift too.

“I do not think the Singapore climate rally can claim that we know in the fossil fuel workers’ interest what is the best way,” said Kumarr. But he added that they will be up for any engagement that would help them along.