New oil and gas capacity grew by 13 per cent globally last year, casting a cloud over the likelihood of meeting climate targets and avoiding the worst consequences of climate change.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

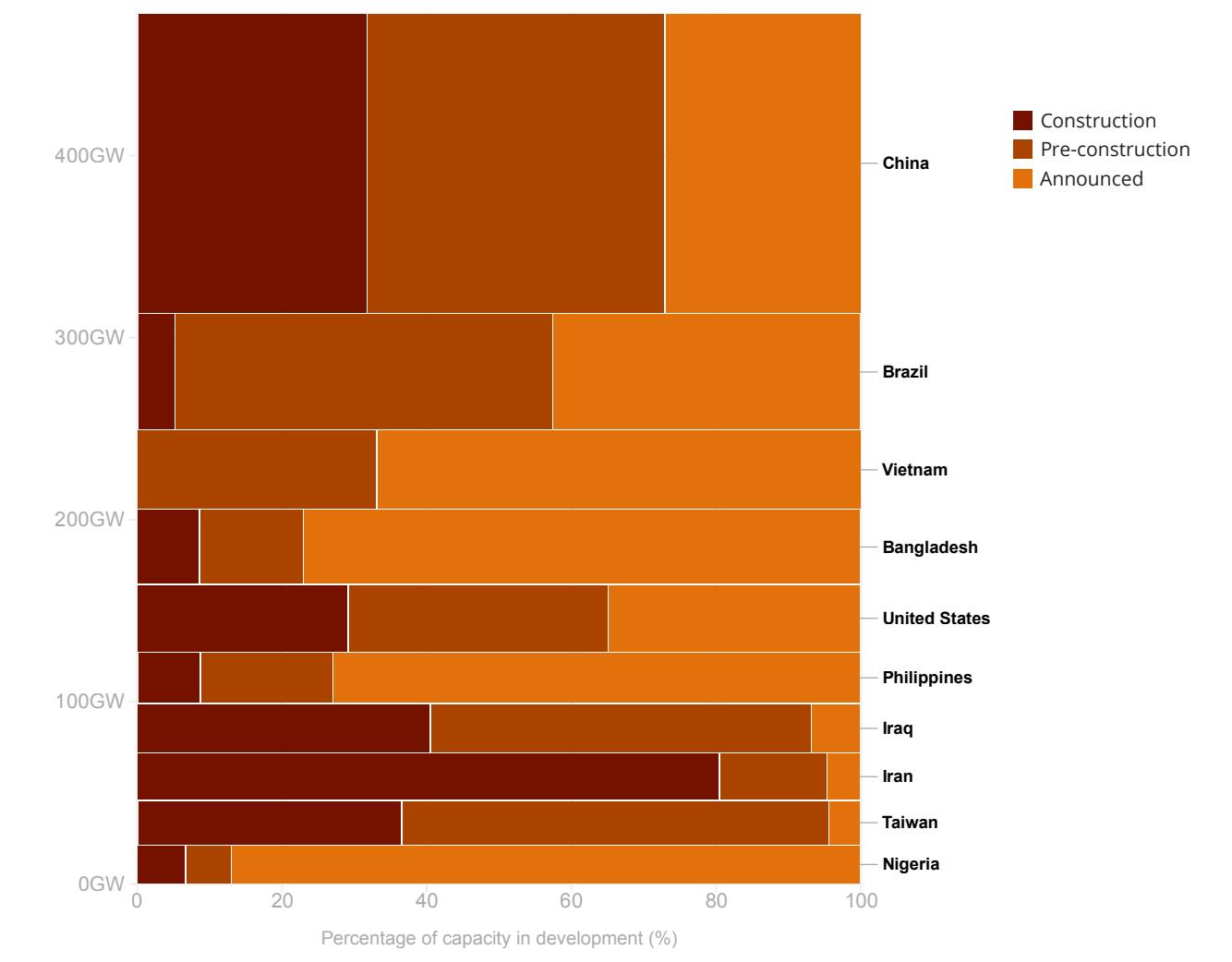

According to a new study by non-profit Global Energy Monitor (GEM), 783 gigawatts (GW) of oil and gas projects were announced or are in the pre-construction and construction phases in 2022.

If this capacity is built, the global oil and gas fleet will grow by a third at an estimated cost of US$611 billion, and create emissions equivalent to six and half years of the United States’ domestic carbon footprint over their lifetime, said the report, published last Thursday.

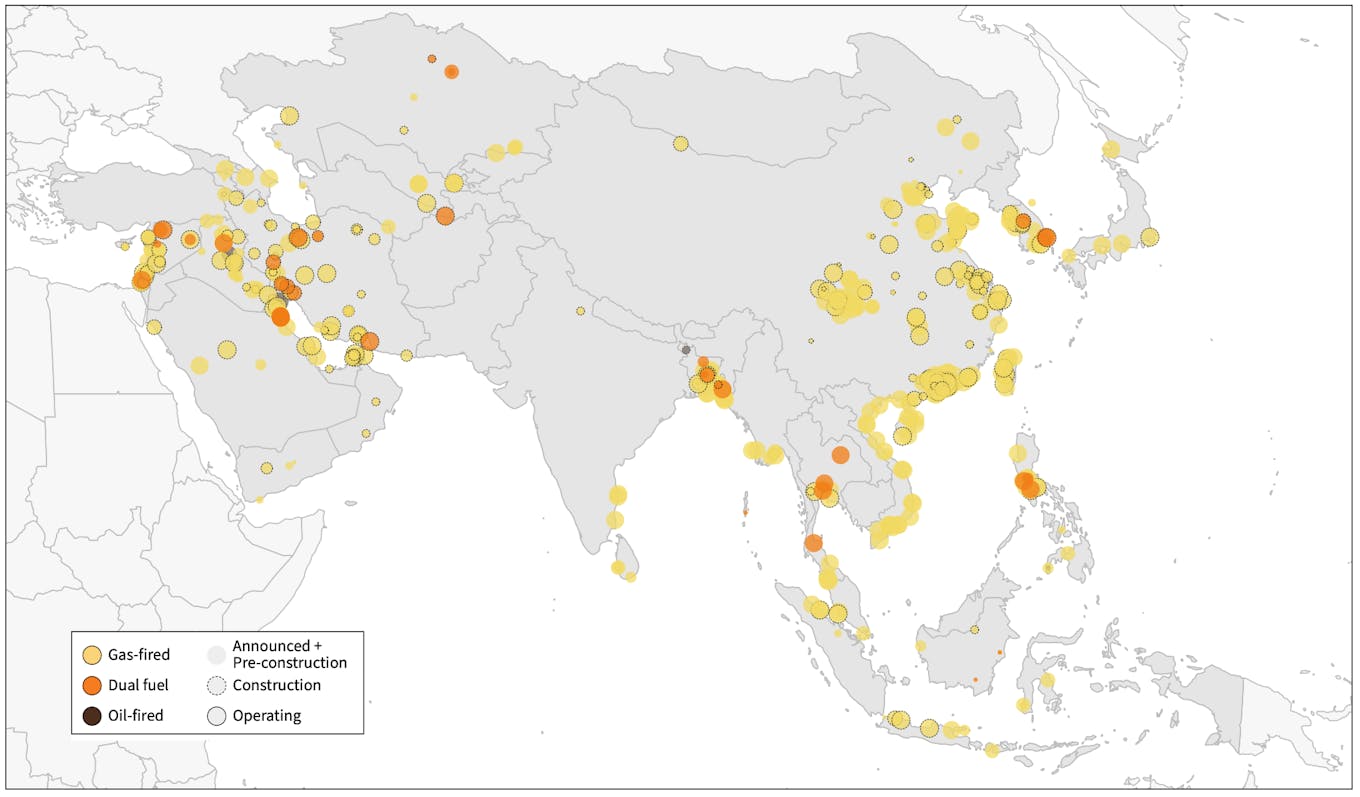

Oil and gas plants under development globally [click to enlarge]. Source: Global Oil and Gas Plant Tracker, Global Energy Monitor

Almost three-quarters of this new capacity – 514 GW, at an estimated cost of US$385 billion – is being built in Asia, with one-fifth (21 per cent) of global supply under development in China, and a sizeable chunk of new projects in Vietnam, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

The push for more oil and gas is partly a response to the liquified natural gas (LNG) crisis of 2022, when LNG prices shot up as Europe pivoted away from Russian gas, prompting countries to boost domestic production and build up LNG infrastructure and storage facilities, the report reads. Japan and India have both announced plans to boost domestic gas storage over the past year.

It is also the result of countries switching from coal to a less carbon-intensive fuel source as they work towards climate targets, with natural gas being aggressively marketed in Asia as a greener power source.

Map of new and existing oil and gas facilities. A large concentration of these facilities are in Asia Pacific. Source: Global Oil and Gas Plant Tracker, Global Energy Monitor

Map of new and existing oil and gas facilities. A large concentration of these facilities are in Asia Pacific. Source: Global Oil and Gas Plant Tracker, Global Energy MonitorDespite the expansion of the oil and gas sector, energy watchdog International Energy Agency said last Tuesday that the world’s demand for oil, gas and coal will begin to fall this decade in “the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era”.

On the other hand, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIA)’s recent projections indicate that global natural gas demand will continue growing beyond 2030, due to strong demand for natural gas in Asia and from the blue hydrogen industry. China’s gas demand will grow by 40 per cent from 2021 to 2030, according to EIA estimates, as the country bets on gas and renewables to decarbonise its energy system.

The GEM report’s authors question the role of natural gas as an interim “transition fuel” as the world pivots to clean energy. Jenny Martos, project manager for GEM’s Global Oil and Gas Plant Tracker, said that gas’ reputation as a cheaper, cleaner and reliable transition fuel is “unravelling”.

She pointed to growing awareness of the climate impacts of methane leaks from gas production and extreme weather disrupting gas facilities. The report pointed to the “false narrative” of the reliability of fossil fuels, citing the example of gas plant failure in the United States last December, when dozens died in extreme winter cold.

Expanding oil and gas capacity represents a stranded asset risk while also diverting resources away from the transition to clean energy, the report noted. Installed renewable power capacity will need to triple by 2050, according to the IEA.

The report pointed to 2022 analysis by TransitionZero, a think tank, which found that the costs of electricity from solar and wind are on average below the cost of gas-fired power, and well below such costs in China.

The transition from oil and gas to cleaner fuels is not happening “anywhere near fast enough,” Martos said.

GEM’s study emerges the week after research by consultancy Wood MacKenzie projected that oil demand must fall from 2023 onwards for global warming to be capped at 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels, in line with the Paris Agreement.

In 2021, International Energy Agency warned that if the world is to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and avoid the worst consequences of climate change, there can be no new coal, oil or gas developments.