Non-profit group World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has published a report shining an uncomfortable spotlight on Asian consumer firms, which finds them severely lagging behind international standards on sustainability.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The international group said the lack of sustainability among Asian manufacturers of food, household, and personal care products is in part due to a lack of scrutiny from financiers.

In a new report, titled ‘Asian Fast Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) – A Sustainability Guide for Financiers and Companies’, WWF noted that Asian companies and their investors are not doing enough when it comes to managing their environmental risks.

The report, launched at the third Singapore Dialogue on Sustainable World Resources conference organised by the Singapore Institute of International Affairs, analysed sustainability and annual reports from 26 Asian FMCG firms to see how they managed the environmental impact of the three most important elements of their operations, namely water use, packaging, and ‘soft commodities’ such as palm oil, sugar, and meat.

The 26 firms - which all had a market capitalisation of at least US$1 billion each - were picked from China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam.

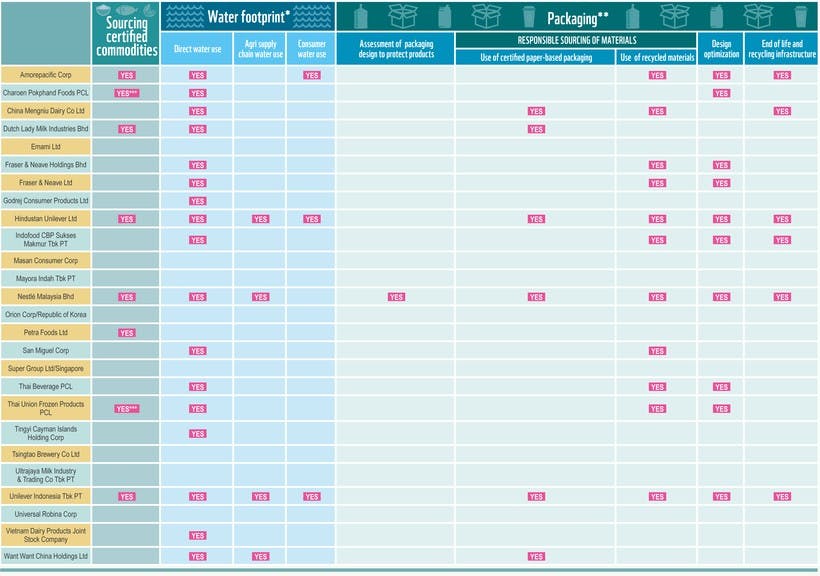

WWF’s tabulation of how 26 Asian FMCG companies report their sustainability efforts. (Click to zoom) Image: WWF

Jeanne Stampe, co-author of the report and Asia finance and commodities specialist, WWF, shared that the analysis revealed that overall, Asian companies were less aware of environmental, social, and related business risks than their western counterparts.

This is evident from their lack of responsible practices such as sourcing certified sustainable commodities and policies requiring a company’s suppliers to reduce their water use, among other things.

“Corporate disclosure, investor engagement, and due diligence by lending banks are also low in the region, though this is starting to change,” said Stampe.

Consuming the planet

The industry, which is a major driver of economic growth in Asia, also has a huge impact on the environment, said WWF in its report.

For example, growing agricultural commodities in Asia have often been linked to deforestation and illegal activities such as burning to clear land. This in turn generates millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions which drive climate change.

FMCG companies are also heavily reliant on water for irrigating crops for consumption and livestock cultivation, factory operations, and producing beverages, among other things. As consumer demand in Asia increases, the sector’s water footprint will also grow.

These firms also use extensive amounts of packaging, which is vital for protecting products from damage, but geenrates waste that is not always biodegradable or recyclable.

FMCG companies which are responsible for such damage may “emerge unscathed” from economic consequences in the short run, but these pressures will catch up with them in the mid-to-long term, said WWF. This is because depleting the very resources companies rely on for revenues and growth will undermine their ability to survive in the future.

They also face operational risks if environmental impacts continue unchecked. For example, a lack of clean water could bring a factory’s production to a halt, and floods can also disrupt a firm’s operations, as was seen in Thailand in 2011 when floodwater destroyed many factories in Bangkok.

Furthermore, environmental awareness among consumers is growing, and many retailers are also pledging to only stock products that are made by environmentally responsible companies.

Errant firms risk damage to their brand reputation and may lose revenues as the public and stores reject their products.

Ben Ridley, Asia Pacific head of sustainability affairs at Credit Suisse, which sponsored the WWF report, said that “the FMCG sector’s vulnerability to extreme weather events and water and food crises emphasises the need for companies and financiers involved in the sector to better understand and manage such risks”.

“Active participation through multi-stakeholder platforms to jointly develop, implement and promote practicable and acceptable sustainability standards has now become imperative,” he added.

Growing sustainably

While poor environmental management can leave an FMCG company exposed to various risks, choosing to operate sustainably can have many benefits including positive branding opportunities and a reduced chance of violating regulations on sustainability and social responsibility, said WWF.

Many global groups of investors are also moving to shift their funds to more sustainable assets.

One of the many initiatives which support this includes the United Nations-backed Principles for Responsible Investment, which has 1,325 signatories with a combined US$45 trillion in assets under management. These investors have committed to engage companies in their portfolio on environmental and social risks.

WWF, in their report, recommended practical ways for companies to cash in on these benefits by practicing sustainable commodity sourcing and good water stewardship, and reducing the environmental footprint of their packaging.

For soft commodities, environmental certifications such as the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and Marine Stewardship Council are one of the best ways to ensure sustainable supply chains, said WWF.

WWF’s analysis showed that only eight out of the 26 Asian companies surveyed sourced certified commodities, including Unilever Indonesia, Hindustan Unilever from India, Nestle Malaysia, and Malaysian firm Dutch Lady Milk Industries.

FMCG companies should also reduce the water that is used in their own operations and also by their upstream suppliers and downstream consumers, said WWF. But while most of the 26 companies reported measures to reduce water use in their own operations, only five had measures in place to encourage suppliers and consumers to do the same.

Among these were Hindustan Unilever and Unilever Indonesia, which are guided by their parent group’s commitment to sustainable agriculture and its mandatory requirements for suppliers on water use and management.

Meanwhile, Chinese firm Want Want China Holdings addresses water scarcity by encouraging farmers in its supply chain to grow plants which require less water to grow, and training them on water saving irrigation methods.

When it comes to packaging, companies not only need to improve the resource efficiency of their boxes and bottles, but also make them easy and convenient to recycle, urged WWF.

There are advanced options available to do this, such as a technology developed by Unilever Netherlands and their partners to inject gas into bottles while moulding them, so they use less plastic but are still recyclable.

But simple solutions such as printing a label directly on a bottle instead of using a separate plastic piece can also save resources and cut costs by half; and using recycled dark bottle-caps instead of white or clear ones - which are difficult to make using recycled plastic - can save 20 per cent of a bottle’s manufacturing cost.

Despite the variety of solutions available “companies alone do not have the means to move towards more sustainable products”, noted Stampe.

Investors should use the information in the WWF report to ask companies in their portfolios about their efforts to manage environmental risks, and for new investments, use their economic clout to fund more sustainable practices.

“Support from financiers through active investor engagement and due diligence by lenders is essential,” said Stampe.