The world is entering climate crisis mode, and businesses know it. But whether they are addressing climate risk and pivoting to the new opportunities of a low-carbon world fast enough is up for debate.

The private sector plays an outsized role in the climate conundrum. It emits most of the world’s greenhouse gases, but its green pledges also amount to 60 per cent of all emissions cuts countries have committed to under the Paris Agreement, according to estimates by non-profit World Resources Institute and industry group We Mean Business.

In recent years, building a “sustainability culture” has become a hot talking point in corporate boardrooms – influenced by both consumers and employees, as well as a growing recognition of its ability to serve as a unique selling point – even as exact definitions of sustainability culture depend on who you ask.

It is about attributes like codifying rules and procedures, providing room for innovation, and encouraging engagement between staff members, according to Canada industry group Network for Business Sustainability, which boasts of over 35,000 experts in its fold. A separate study last year points to embedding green practices into firms’ values and beliefs.

Defining features also include proper climate disclosures and selling green products, according to Professor Lawrence Loh, director of the Centre for Governance and Sustainability at the National University of Singapore.

“A true sustainable culture needs a 360-degree incorporation of sensitivity, awareness and more importantly, the application of sustainability by everybody, in everything you do for the organisation,” he added.

Those already pursuing a sustainability agenda speak of material benefits.

For French technology firm Schneider Electric, embedding sustainability into product design meant producing electrical components that do away with sulfur hexafluoride, a common gas used for insulation that is 23,500 times more potent than carbon dioxide in heating the Earth.

It has made its products more attractive to clients, as it helps them present lower emissions figures in their sustainability reports, according to Jackson Seng, vice-president of sustainability and strategy at Schneider Electric.

Such disclosures are being mandated by bourses worldwide, and increasingly scrutinised by investors eager to slash portfolio emissions.

“

Employees are looking for that sentiment and corporate vision that provides evidence for steering the company in the right direction in reducing their carbon footprint, and doing right by the environment.

Elisha Harrington, senior director, Chief Innovation Office, ServiceNow

Firms are also working together to build new businesses around the demand for sustainability services, said Elisha Harrington, senior director in the chief innovation office at United States-based digital workflow firm ServiceNow. She pointed to the establishment of carbon offsets trade platform CarbonPlace in 2020 by major banks across the world as an example.

The impetus to build sustainable cultures comes from within firms too, Harrington added.

“Employees are looking for that sentiment and corporate vision that provides evidence for steering the company in the right direction in reducing their carbon footprint, and doing right by the environment,” she said.

Organisational challenges

The corporate world has long been trying to distill the concept of sustainability into measurable specifics, by classifying issues into environmental, social and governance (ESG) categories. But firms are still struggling with exactly how such issues should be dealt with.

A study last year by marketing agency ThoughtLab involving over 1,000 executives last year found that half of them thought addressing environmental and social risks generates value, but only a quarter are taking steps to leverage opportunities. Managing ESG risks is something survey respondents said they would do in the next one to two years, but not now.

Another survey by US firm L.E.K. Consulting found that while business leaders were willing to sacrifice short-term financial performance to address ESG issues, many say their firms cannot agree on how much of a trade-off is acceptable.

It could be a data problem, according to Harrington.

“It is on every organisation to, if they haven’t already started, gather data and revamp their existing frameworks to collect environmental footprint data,” said Harrington. Such information can help improve workflows and control over sustainability issues, she said.

Different offices also need to talk to each other about what works and what doesn’t, Harrington added.

“Operations, supply chain, procurement – a lot of those departments can be quite siloed”, so firms need a coherent platform to aggregate initiatives, share ideas, and provide a unified response to the market, she said.

Still, the order has to come from the top, said Loh.

“Sustainability has always been the job of something called the sustainability department,” he said.

“Sometimes they’re placed in other functions like finance or even corporate communications. But I think we need to move beyond a functional, specialised approach. My view is that it should be an integral part of the leadership team,” he added.

Businesses seem to have taken heed. In the ThoughtLab study, commissioned by ServiceNow, some 80 per cent of over 1,000 C-suite executives polled last year said it was within their remit to look into ESG matters.

But their actions may not be going far enough. Consultancy firm Deloitte found that executives are prioritising actions like using recycled materials and improving energy efficiency, over what the consultancy considered more effective steps, such as developing climate-friendly products and fighting for the environment in their lobbying efforts.

“Companies are less likely to implement actions that demonstrate they have embedded climate considerations into their cultures and have the senior leader buy-in and influence to effect meaningful transformation,” the report said.

Regulators are wading in to make sure corporate senior leaders toe the ESG line. Earlier this year, Singapore’s stock exchange started requiring directors of listed companies to take lessons on sustainability reporting rules. Hong Kong’s bourse asked firms to disclose the training they provide to directors and staff against corrupt practices in 2020.

Giving a false impression of ESG credentials is also getting dangerous, with the police raid in May of Deutsche Bank’s asset management arm over greenwashing allegation setting off alarm bells in the industry. Singapore has also recently set stricter guidelines for retail ESG funds.

Loh added that corporate leaders must also be given the “right incentives” to act on sustainability, by tying their pay to ESG metrics. In a study of 650 listed companies across Asia Pacific, only 16 per cent link ESG performance to their top executives’ pay, with an outsized number of Australian firms.

There is still a place for a chief sustainability officer within the highest echelons of corporate leadership, Loh said, to coordinate practices across the organisation, but not to take control of functions traditionally held by other top executives.

“

Sustainability has always been the job of something called the sustainability department…sometimes they’re placed in other functions like finance or even corporate communications. But I think we need to move beyond a functional, specialised approach.

Professor Lawrence Loh, director, Centre for Governance and Sustainability, National University of Singapore

Challenges in Asia-Pacific

The region over four billion people calls home still lags in several typical metrics of corporate sustainability culture, compared to its Western neighbours.

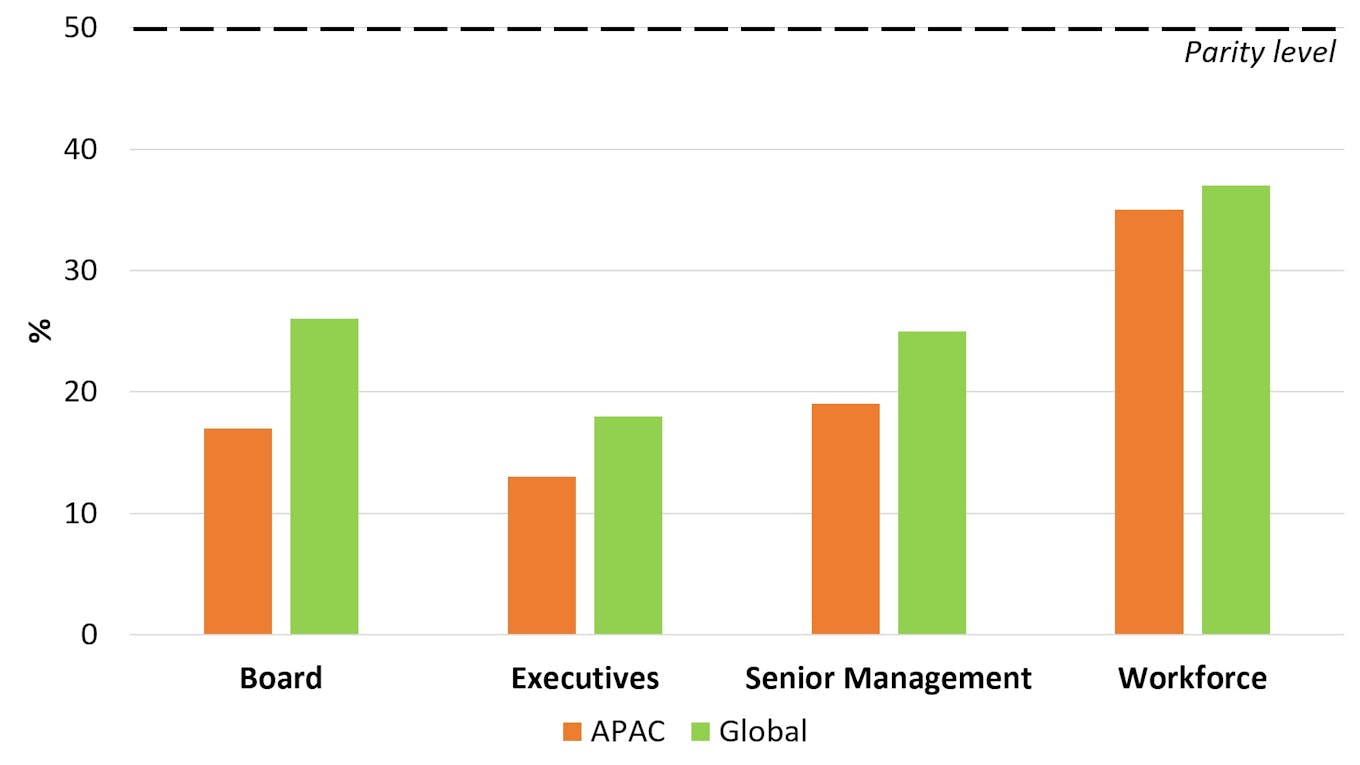

Green rules are generally laxer in Asia Pacific compared to Europe, while the proportion of electricity generated from fossil fuels is about double. Women also take up fewer leadership roles in Asia Pacific firms compared to the world, according to a recent report by gender equality think-tank Equileap.

Female representation at work in Asia Pacific and worldwide. Data: Equileap.

Asia Pacific is still in the process of aligning with global standards on corporate sustainability, said Loh, adding that the culture is more established in the European Union because of long-standing regulations. For example, the EU has had a carbon trading system up since 2005, and legislation against workplace sexual harrassment since 2002.

Progress in Asia Pacific countries could be slower too because of cultural differences that could affect conversations on diversity and human rights, Loh said. “A certain convergence is necessary for a global business order, but at the same time we cannot force the pace such that it might upset local cultures.”

Nonetheless, Loh said a broader view of sustainability is starting to emerge in the region, pointing to how Malaysia’s rubber and palm oil industries have been accused of forced labour and human trafficking by United States authorities and local non-profits. These industries have traditionally grappled mainly with environmental issues such as deforestation and air pollution from land-burning practices.

Seng said finding workers with both the technical know-how in the electronics field and an understanding of decarbonisation in business strategies is challenging in Asia. Schneider Electric looks out for people who can learn on the job, and has crafted internal training programmes to groom talent.

“This is a new skill set that we’re looking at today,” Seng said.

“If we cannot attract such talent from outside, then we will have to train our own people. Today, this is a big challenge for me,” he added.

The next challenge, Seng said, is to get smaller firms on board. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) make up the backbone of many economies in the region. They account for 97 per cent of businesses in Southeast Asia and emit 2 per cent of the region’s annual greenhouse gases. ESG compliance rules, written for larger publicly-listed firms, generally do not influence how smaller firms operate.

“SMEs do not have the resources or manpower to (look into sustainability). So how do we create something to support this group of companies? I think that’s the next big topic to discuss,” Seng said.