For many living in the rural villages of Hebei region in China, the winter of 2017 was unbearably cold.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In a bid to swiftly reduce air pollution levels, realising in the summer that same year it was not on track to meet its air quality goals, China’s central government had launched a campaign to remove coal-fired boilers in a wide swathe of Hebei province, in some cases before natural gas or electric replacements were available.

The aggressive move left entire villages without heating for the winter, and the internet buzzing with complaints about fuel shortages. No deaths were officially logged, but a directive from the environment ministry had acknowledged “anxieties about fuel sources to provide heating”; the BBC and other media called it a “heating crisis“.

This abrupt coal ban attempted by the Chinese authorities, which later had to be suspended, is one example highlighted in a recent report on air pollution that warns China of the social repercussions of rigid “command-and-control” policies in its “war on pollution”.

“The country needs to place more emphasis on market-based approaches,” said the report by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC). It recommended for China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gas, to shift its focus to relying on emissions trading schemes for pollution reduction. “This would allow China to sustain its current efforts at a lower cost and without intense stakeholder pressure.”

Decline in global pollution levels ‘due entirely to China’

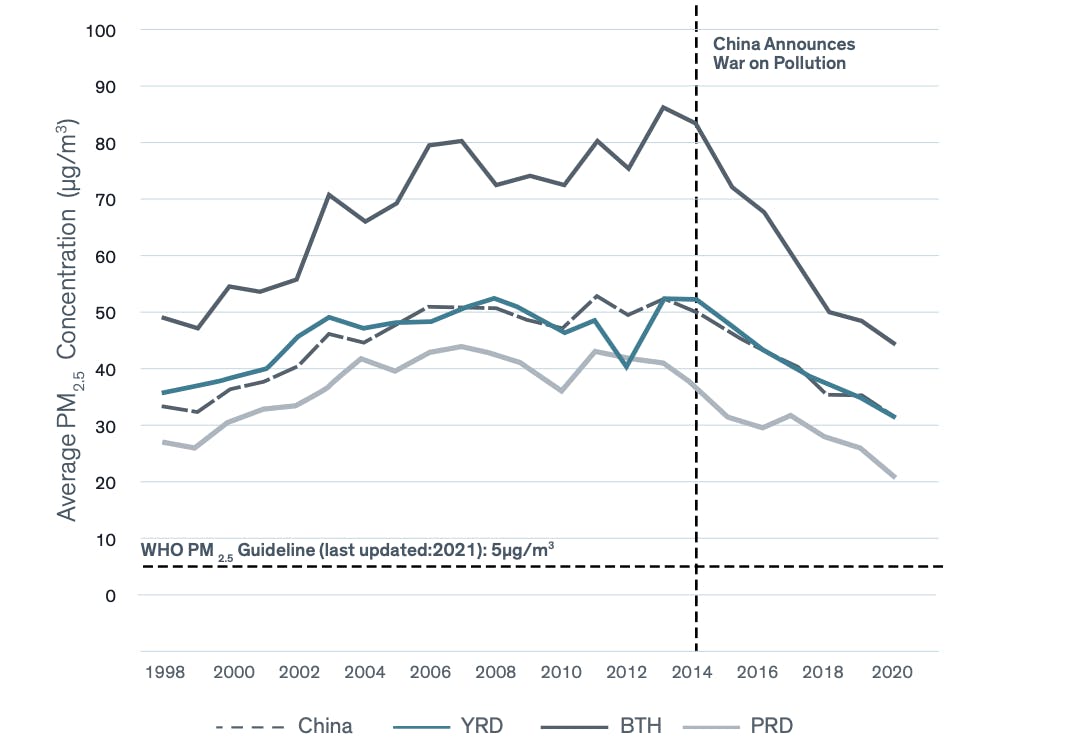

The Air Quality Life Index (AQLI), released this month, does credit China for its successful measures in tackling particulate pollution. Data shows that the pollution level in China had dropped 39.6 per cent from 2013 to 2020.

From 2019 to 2020, air pollution levels fell by 9.1 per cent. In Beijing, China’s capital, the annual level of PM2.5, fine particles less than 2.5 micrometres in width that penetrate deep into the lungs and a key indicator of pollution monitoring, fell by 8.7 per cent in the same period.

PM2.5 concentrations in major regions in Mainland China over time. PRD = Pearl River Delta, including Guangdong, and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau; YRD = Yangtze River Delta, including Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang; BTH = Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. Image: AQLI

“The world has seen a decline in average pollution levels since 2013, and the decline is due entirely to China,” said the report, stating that the population-weighted global average particulate pollution would have ticked up slightly without China’s “war on pollution”, which is now into its eighth year. “Its impacts are persistent and tangible.”

“Due to these improvements, the average Chinese citizen can expect to live two years longer, provided the reductions are sustained,” it said. The report finds that if China further reduces its pollution from 2020 levels to meet the World Health Organisation guidelines for healthy air, average life expectancies would be extended by 2.6 years.

The question, however, is if China can meet and sustain these pollution reductions. For the past decade, the Chinese government has closed, relocated and reduced the production capacity of a large number of polluting firms, enforced tighter emission standards across industries, assigned strict abatement targets to local governments and sent thousands of “discipline teams” for inspections and audits at the local level to ensure performance.

“While the measures have worked, they have come with significant social costs,” said the report, highlighting pushback from stakeholders who took to social media platforms to complain about environmental regulations which were too stringent, and from workers laid off by polluting firms. “While effective in reducing the total emissions in the country, the measures have ignored the significant differences in abatement costs across firms, industries and regions, and led to large economic and administrative costs in achieving the policy goal.”

China’s lesson for Southeast Asia — raise fuel standards

Despite introducing a national carbon market — one positioning China well for the adoption of a particulate pollution trading scheme — in July last year, signs point to the state largely continuing its top-down approach for environmental enforcement. In an interview with a government-run magazine in April this year, Peking University’s director of the Centre for Environment and Health, Zhu Tong, said a clamp-down on polluting industries is required for China to see cleaner air.

Zhu is China’s leading scientist in atmospheric pollution and has been advising the Chinese government on controlling air pollution in the lead-up to major international events, including the 2007 Beijing Olympics. He also said that China’s experience with pollution control and the relevant technical know-how can be shared with other countries which face similar challenges.

“

The world has seen a decline in average pollution levels since 2013, and the decline is due entirely to China.

Air Quality Life Index, June 2022

These could include Southeast Asian countries, which continue to see a rise in pollution, according to the AQLI report. The latest data shows that virtually all of Southeast Asia’s roughly 650 million people live in areas where particulate pollution exceeds 5 μg/m3, the amount considered safe to breathe by the World Health Organisation (WHO). In 2020, decreases in pollution levels were registered in Singapore and Indonesia, driven by a lower number of fires on the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo, but in Cambodia and Thailand, PM2.5 levels increased by 25.9 per cent and 10.8 per cent, respectively, largely due to seasonal forest and peatland fires, as well as high vehicle emissions.

The report called air pollution a stubborn problem, and recommended for Southeast Asia to take a leaf out of China’s book and implement stricter fuel standards, as well as enforce controls on industrial emissions.

For now, fuel standards in Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand are much lower than those in China and India, said the report, allowing for harmful emissions of nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide, or NOx. Vehicles in these countries are only required to meet Euro-4 standards, which allow for up to three times as much of NOx emissions, and five times as much sulphur content.

Indonesia’s coal-fired power plants — of which there are around 10 within a 100-kilometre radius of its capital Jakarta — are allowed to emit three to 7.5 times more particular matter, NOx and sulphur dioxide than China’s coal plants.

“Strong clean air policies — like those targeting fossil fuel combustion — are still important for reducing particulate pollution concentrations and increasing life expectancies, along with the co-benefit of reducing the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change,” said the report’s authors.