Diplomats from around the world gathered in Germany over the past two weeks for the latest round of UN climate talks.

The “intersessional” talks, which take place in Bonn each year midway between the annual conference of parties (COP), aim to move negotiations forward ahead of the larger meeting which take place towards the end of the year.

A range of topics were on the table this year, including the detailed “rulebook” on how to implement the Paris Agreement, which must be finalised at COP24 in 2018.

Negotiators worked to iron out details of a stock-taking exercise in 2018, which will measure progress toward the Paris goals, and to move forwards with the sticky issue of adaptation finance.

All of this as countries continue to grapple with the uncertainty over whether US president Donald Trump will or won’t pull out of the Paris Agreement.

Carbon Brief takes a look at the major themes and points of controversy to come out of the talks. We have also collated a schedule of upcoming deadlines, reports and meetings under the Paris negotiating track, in the lead up to COP23 in November.

“

There still needs to be an element where you take national circumstances into account, and that’s the area of flexibility…but the real fact of the matter that’s happening here at the moment is how do you apply the mechanism of flexibility when it comes to reporting and review.

Neoka Naidoo, transparency coordinator, Climate Action Network international

Trump threat

The news during last November’s COP22 annual climate conference in Marrakesh that Donald Trump had won the US election cast an initially heavy shadow over negotiations, not least because one of Trump’s campaign pledges was to pull out of the Paris Agreement.

Four months into his presidency, Trump has yet to announce a final decision on whether he will follow through on this pledge. Despite weeks of media titbits of the to-ing and fro-ing in his cabinet’s closed-door discussions, it remains hard to say what the final outcome will be.

The signals remain mixed. The US signed up to the Fairbanks Declaration, a joint statement of the eight-member Arctic Council that acknowledged the Paris Agreement (having lobbied behind the scenes to water down its language on climate change). But it sent a much-diminished delegation of seven to Bonn, versus 44 last year.

Nevertheless, multiple reports noted that in Bonn the discussions on the finer details of the Paris Agreement went ahead relatively smoothly in the face of this uncertainty, with envoys unusually cooperative as they strive to move ahead with implementing the deal.

“This has gone as far as we could have expected,” Yamide Dagnet, senior associate at the World Resources Institute tells Carbon Brief. “Negotiators will leave Bonn with a roadmap towards COP23.” Dagnet says the talks were marked by determination to make progress.

Stepping stones

The Paris Agreement set out the overarching goals and framework for international climate action, but left many details to be filled in later. These questions, collectively known as the Paris “rulebook”, include who should do what, by when, how and with what financial support.

For instance, it will address how countries communicate their efforts with regards to mitigation and adaptation, climate finance, transfer of technology and capacity building, how they will be held accountable for their commitments, and how collective efforts will be reviewed (and ambition increased) over time.

The process of working out these details began in earnest at COP22, in Marrakesh last November (see the Carbon Brief summary). It continued over the past two weeks in Bonn.

Official conclusions from the meeting, published yesterday, begin by reiterating the firm deadline to complete the Paris rulebook by COP24, in November 2018, at the latest.

The conclusions say that “substantive progress has been achieved” over the past two weeks, with this progress captured in a series of informal notes. However, with typical diplomatic hesitancy, it explains that these notes:

“Attempt to informally capture the views expressed by some Parties to date…[and] do not necessarily reflect the view of all Parties. The notes are not intended to prejudge further work that Parties may wish to undertake, or to prevent Parties from expressing other views they may have in the future. The views presented in the notes…do not signify any consensus among Parties or imply the basis for any future negotiations.”

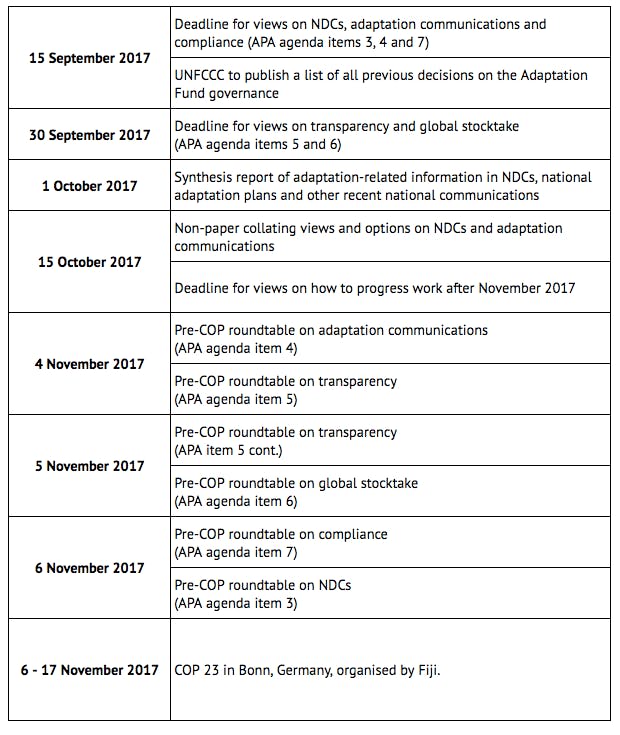

Finally, the conclusions set out a series of stepping stones towards COP23, which will also be held in Bonn, this November.

Diary dates

Under each topic, parties are invited to submit their views during September 2017. These views will be collected together in another series of papers, with the aim of setting out options for draft text on the rulebook, as well as areas of agreement and disagreement.

“Negotiators [now] know what the stumbling blocks are and where creative thinking will be needed…to advance thinking,” WRI’s Dagnet says.

Negotiators will then reconvene at a series of roundtable workshops, held in early November in advance of COP23 in Bonn. The dates for each issue vary: see the table below for details.

The work of the APA continues according to an agreed agenda, with working groups for each agenda item. These include: “agenda item 3” on the contents of and accounting for nationally determined contributions (NDCs); “agenda item 4” on how parties should communicate their adaptation efforts; “agenda item 5” on how parties will transparently report on action they take and on support they give to others; “agenda item 6” on a global stocktake in 2023, where collective progress towards the Paris targets will be checked; and “agenda item 7” on how compliance with the Paris Agreement will be monitored. Agenda item 8 covers other business, including the Adaptation Fund (see below).

Global stocktake

Under the Paris deal, parties agreed they would come together for a “global stocktake” in 2023 and every five years afterwards to measure their collective progress.

COP21 also agreed to undertake a similar process in 2018. Dubbed the “facilitative dialogue”, it aims to measure progress and inform the next round of NDCs, due in 2020.

However, the concrete rules and guidelines over how to do this are yet to be agreed upon. With the facilitative dialogue not set to take place until COP24, progress in this session was slow.

While some had hoped there would at least be concrete progression on the “headings” to be contained in the rulebook, this session resulted only in an “informal note” which collected together parties’ divergent views, rather than any consensus.

One key issue of disagreement is the scope of the process and what progress will be assessed against – for instance how do you measure global progress towards the adaptation goal of the Paris Agreement.

“Even for [the] mitigation long-term target, there will be different understandings, let alone other areas,” Naoyuki Yamagishi, a climate and energy leader with WWF Japan, tells Carbon Brief. However, Yamagishi – who has been involved in the process for 14 years – says he “wouldn’t be so easily disappointed”. He says:

“It would have been, of course, great if we already had an agreed headings and subheading of the global stocktake part of the rulebook. However, if you listen to the discussion in the informal meetings during the session, you could see that issues to be resolved are getting clearer and [there was] some level of convergence, which I would describe slow but important progress.”

Transparency

Another process established by the Paris Agreement was the “enhanced transparency framework”, which aims to “build mutual trust and confidence and to promote effective implementation” by formalising the ways countries report and review their own progress, as well as the support they have provided to others.

The framework is scheduled to be completed by the end of COP24 in 2018, meaning a draft text is needed by this year’s COP23 in November to ensure there is enough time for negotiations over it to take place.

However, as for the facilitative dialogue, negotiations on transparency are currently still centred on which different areas should be included, and what the procedures and guidelines should be.

For instance, the Paris Agreement included a voluntary option for parties to submit formal communications on their adaptation plans, progress and needs. But it is not yet clear how this would fit in with the transparency framework.

In addition, negotiators are still trying to iron out how best to ensure that the transparency and reporting requirements are flexible enough to avoid them becoming an additional burden on developing countries, while also avoiding any unnecessary backsliding.

As Neoka Naidoo, transparency coordinator at Climate Action Network international, tells Carbon Brief:

“There still needs to be an element where you take national circumstances into account, and that’s the area of flexibility. So at the moment in these negotiations flexibility is quite a theoretical term, it’s like yes we need flexibility because we all have different national circumstances. But the real fact of the matter that’s happening here at the moment is how do you apply the mechanism of flexibility when it comes to reporting and review.”

Climate finance

Developed countries pledged in 2009 to jointly “mobilise” $100bn per year by 2020 to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change, and the Paris Agreement again recognised the importance of this climate finance.

Negotiations on this section of the Paris rulebook, taking place under the transparency heading, are focused on how to account for and track the climate finance that countries have given or received. The result, again, was a collection of informal notes which will form a basis of discussion for COP23.

One related area of contention is the future of the Adaptation Fund, a (relatively small) pot of money created in 2001 as part of the Kyoto Protocol, which provides grants to vulnerable countries to adapt to the impacts of climate change.

While countries agreed in Marrakesh that the fund should also serve the Paris Agreement, decisions on its governance and operations have proved contentious, and delegates left Bonn only with an informal paper that sets out the different options and the Secretariat’s legal analysis of some of the key questions.

Joe Thwaites, an associate at the World Resources Institute, says countries remain deadlocked on the issue. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Developing countries argued that the fund is ready to serve the Agreement right away, and that the decisions to confirm this should happen as soon as possible. However, developed countries did not want to take the decision before examining different options and implications on issues such as changing board membership, future sources of funding, and the role of the fund relative to other climate finance institutions.”

Finally, in one sign of goodwill and (in their words) “increased cooperation”, the EU pledged €800m in support for the Pacific region up to 2020, with around half earmarked for climate action. In a joint statement with the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP) reaffirming their commitment to the Paris deal, the EU also announced €3m to support Fiji’s COP23 Presidency.

However in less hopeful signs, the lead US delegate reiterated that Trump does not currently plan on further contributing to the Green Climate Fund, after his budget proposal in March pledged to cut the remaining $2bn the US had previously promised.

It is also worth noting that the world still remains a long way off from the $100bn climate finance goal.

Peer review

One important part of the Bonn talks, not directly related to implementing the Paris Agreement, was a series of hearings where countries were asked to explain and defend their climate plans, in the face of public questions from their peers.

The process differs somewhat, between a more rigorous format for developed countries and a less formal one for developing nations, but the general idea is the same. See this presentation from WRI for more details.

First, countries submit biennial reports on their plans and progress. Then, their peers submit written questions, and they respond with written answers. (Carbon Brief covered the Q&As for the US, Russia and Japan.) Finally, the debate concludes at public hearings, which were held across the middle weekend in Bonn.

At a hearing on US plans, which are currently under review by the new administration, China and India asked pointed questions on contributions to international climate finance (the US won’t make any this year) and the health benefits of climate action.

In the developing country hearings, India stood out for its optimistic news that the country will achieve its solar energy goals eight years early. Outside the talks, WRI and Climate Action Tracker separately reported on the rapid climate progress being made by China and India.

Separately, Indian energy minister Piyush Goyal told the Vienna Energy Forum: “India stands committed to its commitments made at Paris irrespective of what happens in the rest of the world”, while a declaration from China’s One Belt One Road summit urged those that have ratified the Paris Agreement – which includes the US – to implement it in full.

‘Lifeline’

As negotiators began wrapping up this year’s intersessional a collective of 48 of the world’s poorest nations on Wednesday made a plea for the Paris Agreement to be strengthened.

Members of the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) called the deal their “lifeline” and urged countries to stick to its goal to limit temperature rise to as little above 1.5C as possible.

“Without increased climate action, no country will be great again,” said Emmanuel Guzman, climate change commissioner for the Philippines, in a blatant dig at Donald Trump’s US campaign slogan.

One contentious issue at the talks this year was corporate conflict of interest, with developing countries led by Ecuador repeatedly pressing for tighter rules to prevent fossil fuel firms having influence over the talks.

However, little progress was made towards an outcome, with only a compromise document inviting input from stakeholders by January 2018 on how to “enhance existing practices” on of outside observers to promote “openness, transparency and inclusiveness”.

Meanwhile, while the fraught topic of loss and damage was not explicitly on the agenda this month, vulnerable developing countries continued to emphasise its importance as an issue in COP23 and beyond.

Sven Harmeling, advocacy coordinator at CARE Climate Change, tells Carbon Brief:

“Unfortunately, although the Paris Agreement includes an entire article on loss and damage signalling its political importance, governments have not yet agreed where and how to address this issue from a longer term perspective.”

However the executive committee of the Warsaw Mechanism on Loss and Damage – agreed at COP19 in 2013 – is set to meet this October to refine its plans for the coming years.

Carbon markets

Another issue on the agenda in Bonn was Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which covers market mechanisms, and could provide a route to the creation of global carbon markets. However, despite devoting significant time to discussions, progress was slow.

David Hone, chief climate adviser to Shell tells Carbon Brief:

“[Views] range from a reincarnation of the CDM [UN Clean Development Mechanism, which supported carbon offsets for use under the Kyoto Protocol] through to a large scale mechanism to help countries develop carbon pricing. It will likely have to incorporate a broad spectrum of approaches, with perhaps more emphasis on projects in the near term and operation on a much larger scale in the medium to longer term.

Jonathan Grant, a director at PWC tells Carbon Brief: “Countries are still in brainstorming mode – the draft outputs from the carbon markets discussions are simply long lists of issues.”

Looking ahead

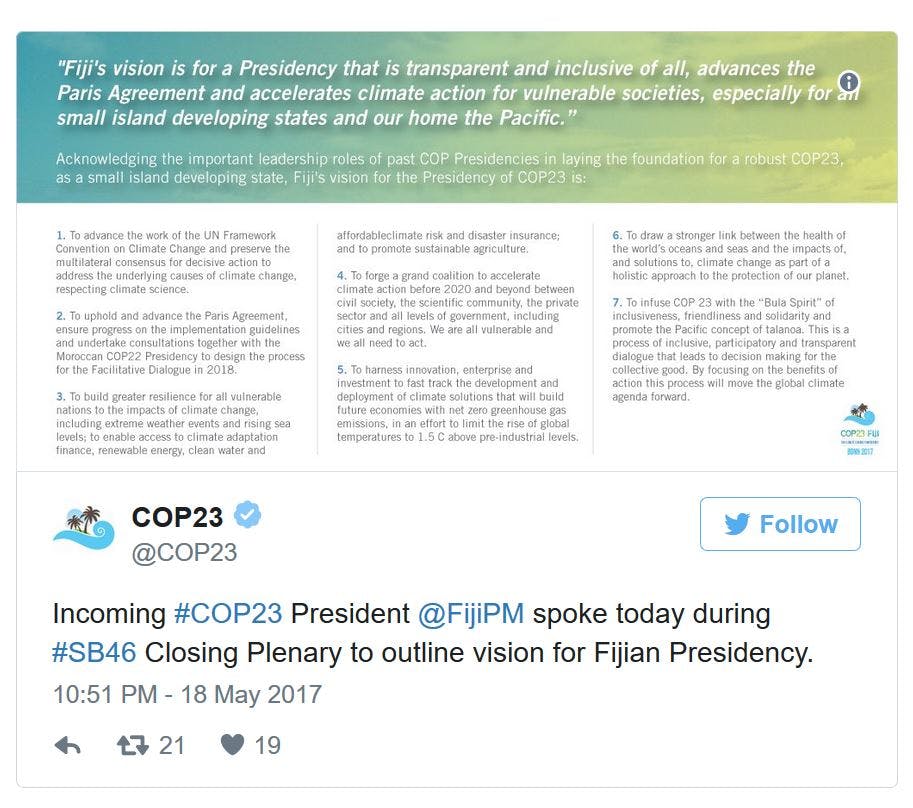

The next big climate conference, COP23, from 6 to 17 November, will be led by Fiji, the first small island state to assume the responsibility. Incoming COP president and Fijian prime minister Frank Bainimarama addressed delegates in Bonn on 18 May, urging the US to remain “in the canoe” as part of the Paris Agreement.

Fiji set out its aims for COP23 in a tweet:

Before then, Germany will host Fiji and others at its annual Petersberg Climate Dialogue, followed by a meeting of the G7 group of leading nations later next week.

Before then, Germany will host Fiji and others at its annual Petersberg Climate Dialogue, followed by a meeting of the G7 group of leading nations later next week.

An EU-China summit on 2 June will have climate “very high on the agenda”. Then, in July, the larger G20 group of nations will meet in Berlin.

As questions continue to swirl over the US approach to climate change, observers will be watching these meetings closely, while lobbying world leaders to pressure Trump on his plans. In a sign of the times for global climate sentiment, recent reports from news agency Tass suggest even Russian president Vladimir Putin could ratify the Paris deal in 2019.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.