The research, published in Nature, uses modelling to map how climate change could shift the geographic ranges of 3,100 mammals species and the viruses they carry by 2070.

It finds that climate change is increasingly driving new encounters between mammal species, raising the risk of novel disease spread. The world’s “biodiversity hotspots” and densely populated parts of Asia and Africa are most likely to be affected.

The findings suggest that climate change could “easily become the dominant [human] driver” of cross-species virus transmission by 2070, the authors say.

The research comes in the third year of the Covid-19 pandemic, a disease passed from animals to humans that has so far killed more than six million people across the world.

“

We are living in the Anthropocene. We are living in an era where our impact on natural ecosystems is going to lead to more pandemics.

Dr Colin Carlson, global change biologist, Georgetown University

In their study, the scientists “caution against overinterpreting our results as explanatory of the current pandemic”, but add the “ecological transition” they have identified will “undoubtedly have a downstream impact on human health and pandemic risk”.

Reshuffling nature

Climate change is shifting where species live. As temperatures increase and rainfall changes, some species are being forced to seek out new areas with climate conditions they are able to tolerate. (Species that are not able to move could face extinction.)

In 2008, a scientific review of 40,000 species across the world found that around half are already on the move as a result of changing climate conditions.

In general, species are seeking cooler temperatures by moving towards the Earth’s poles. Land animals are moving polewards at an average rate of 10 miles per decade, whereas marine species are moving at a rate of 45 miles per decade, according to the review.

As species migrate to new areas, they carry their viruses with them. The new study says there are “at least 10,000” viruses that have the capacity to infect humans, but “at present, the vast majority” of them “are circulating silently in wild mammals.”

The research specifically examines how climate change could affect the likelihood of species coming into contact with each other for the first time as they move into new areas.

This is because new encounters between species are a key element for a “zoonotic spillover” – the passing of harmful pathogens from animals to humans, explains study co-lead author Dr Colin Carlson, a global change biologist at Georgetown University in Washington DC. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Species are going to show up in new combinations because of climate change and, when they do, that’s an opportunity for them to share viruses with each other.”

In addition to pathogen sharing, first encounters between species also provide a platform for viruses to evolve, he explains:

“The best analogy that exists is thinking about wildlife markets. One of the reasons that people are so concerned about spillover risk in markets is that, if you have a bunch of animals in poor health in close proximity, it’s not just a chance for animals to contact humans, it’s also a chance for viruses either to evolve or to jump through a stepping stone host to get to humans. We’ve seen this over and over again with coronaviruses.”

The results show that any amount of future global warming is likely to drive an unprecedented increase in first encounters between mammal species, he adds:

“What we find is the level of change that species will experience because of climate change will basically leave the host-virus network unrecognisable. That makes sense because ecosystems are going to be recognisable. But it’s at a scale that I think is quite stunning.”

(There are many factors that can determine whether a zoonotic spillover turns into a pandemic. For a full breakdown, see Carbon Brief’s explainer on climate change and pandemic risk.)

Viral hotspots

For the study, the researchers used modelling to map changes to the geographic ranges of 3,100 mammal species under various future scenarios.

This includes a scenario where future land use is sustainable and the world is successful in meeting the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping global temperature rise below 2C above pre-industrial levels (“SSP1–RCP2.6”).

It also includes a scenario with “continued fossil fuel reliance” and “rapid land degradation”, where temperatures are likely to exceed 4C (“SSP5–RCP8.5”).

The research focuses on mammals over other animal groups because they have “the highest proportion of [known] viral diversity” and hold the “greatest relevance to human health,” the authors say.

The scientists used these projections to identify where species are likely to encounter each other for the first time in the future.

In addition, they used a “viral sharing model” to predict the probability of cross-species virus transmission.

The results show that “the vast majority of mammal species will overlap with at least one unfamiliar species somewhere in their potential future range, regardless of [the] emissions scenario.”

Under either future emissions scenario, this “would permit over 300,000 first encounters” between species, the study says.

These first encounters between species are projected to lead to at least 15,000 cross-species transmission events of at least one novel virus – “but potentially many more,” the authors say.

These findings suggest that climate change could “easily become the dominant [human] driver” of cross-species virus transmission by 2070, the authors conclude.

By mapping the likely locations of these cross-species transmission events, the authors found that they are likely to be concentrated in biodiverse and highly populated parts of Africa and Asia, Carlson says:

“We think that this process is most likely to impact human health in south-east Asia, east Asia and parts of central Africa – but there are also hotspots in the US and Europe.”

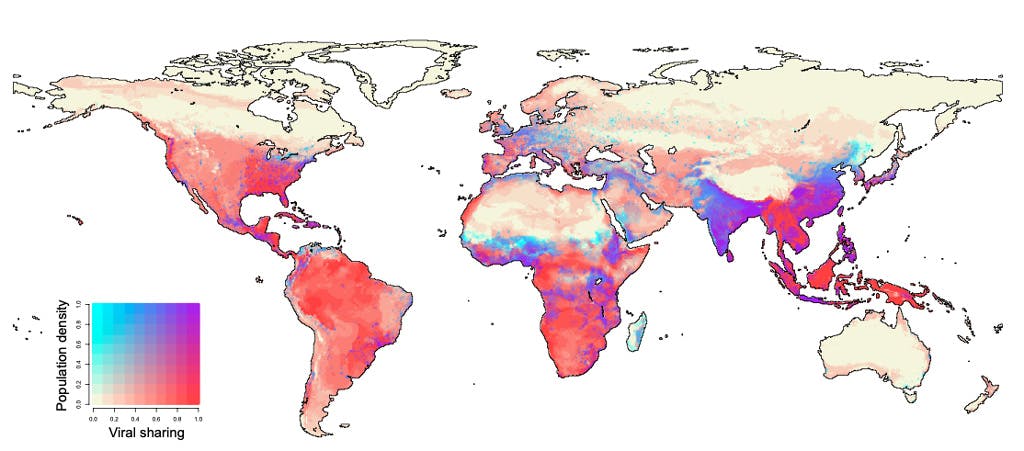

The map below, taken from the study, indicates where viral sharing events are likely to occur by 2070, under the low greenhouse gas emissions and sustainable land use scenario (“SSP1-RCP2.6”).

On the map, purple indicates where a high number of viral sharing events is likely to overlap with high population density.

Where novel mammal viral sharing events are likely to overlap with high population density (purple) under a low-emissions scenario by 2070. Credit: Carlson et al. (2022).

In addition to examining the likely location of viral sharing events, the authors also explored which types of mammals are most likely to be involved in pathogen transmission.

The results show that, among mammal species, bats “account for the majority of novel viral sharing.”

One major reason for this is because bats are one of the only mammals able to fly – allowing them to easily migrate to new areas in response to warming, Carlson tells Carbon Brief.

‘Ecological transition’

One major takeaway of the new research is that an unprecedented increase in virus sharing between mammals is expected under both a low- and a high-emissions scenario – suggesting accelerated action to tackle climate change would do little to alleviate the risks, the authors say.

In fact, the global migration of species in response to global warming to date suggests that the “ecological transition” identified in the study “may already be underway,” the authors say. Carlson tells Carbon Brief:

“We are living in the Anthropocene. We are living in an era where our impact on natural ecosystems is going to lead to more pandemics.”

The findings suggest there is an urgent need to invest in measures to monitor and respond to the emergence of new diseases from wildlife, says study co-lead author Dr Gregory Albery, a disease ecologist at Georgetown University. He told a press briefing:

“The main message is this: this is happening. It is not preventable, even in the best-case climate change scenario and we need to put measures in place to build health infrastructure to protect animal and human populations.”

“Critically, this bolstered infrastructure needs to be paired with active surveillance of wild animals, their movements and their diseases to ensure we can keep our finger on the pulse of global change,” he continued.

The results represent “a critical first step” in understanding how climate change and land use change may raise the risk of “the next pandemic”, says Prof Kate Jones, an ecologist at University College London, who was not involved in the research. She tells Carbon Brief:

“This is an important study, focusing on where the twin pressures of future climate change and land conversion will increase the likelihood of viruses being shared across mammals. However, predicting the risk of viral jumps from mammals into humans is more tricky as these spillovers take place in a complex ecological and human socioeconomic environment.”

“So although this study provides an excellent basis for understanding potential viral exchange hotspots under future change, the actual risk might be mitigated by many other factors. [This may include] an inability for wild species to successfully track changes in climate and land use, viral incompatibilities preventing spillovers into humans – or an increase in investment in health care provision to prevent initial spillovers,” he concluded.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.