Twenty-seven year-old Amy Orta-Rivera from Gurabo, Puerto Rico remembers joining her family for hot chocolate, ‘pan sobao’ (soft baguette) and cheese just before she headed to bed on Tuesday, September 19.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But just a few hours later in the middle of the night, she noticed that everyone in the family was awake and alert.

“Nobody could sleep with all the sounds the rain and wind were making,” Orta-Rivera told Eco-Business in a recent interview. “We kept talking, until we noticed water started to enter the house from a tube that connects the cables of the satellite dish to the TV. At first, the amount of water was small. Then everything changed.”

Little did they know that right then, a nearly Category 5 hurricane called Maria was making a beeline for Puerto Rico, and was going to lash the island with wind and rain that would last for more than 30 hours.

Entrance to the municipality of Gurabo, Puerto Rico. Image: Amy Orta-Rivera

From a meteorological perspective, Hurricane Maria had the elements of a “catastrophic event,” and went on to cause a major humanitarian crisis in key populated cities in Puerto Rico. It became the worst natural disaster on record in nearby island nation Dominica.

As of October 17, 85 per cent of the island still did not have power, Orta-Rivera told Eco-Business. Not much progress has been made towards restoring power two weeks later, with 70 per cent of the island still without electricity. Up to 40 per cent of the population had no water, and those that did only had an intermittent supply.

Orta-Rivera went on to describe a seemingly endless litany of destruction on the island: Schools and universities haven’t been able to open their doors. Many hospitals have had to shut down because of the lack of electricity, and people have been drinking contaminated water. Communication has also been cut off for some others because bridges have collapsed. Thousands have lost their jobs, and businesses have been unable to operate.

“I knew things were going to be bad, but not like this. It feels like we are never going to recover. I know we will, but seeing the panorama it is difficult to believe it,” Orta-Rivera added.

Elizabeth Rivera of Gurabo, Puerto Rico tries to keep water off her house as Hurricane Maria struck on September 20, 2017. Image: Amy Orta-Rivera

Climate trauma: disaster’s hidden toll

To date, the official death toll of Hurricane Maria stands at 51, although media reports show that 900 people have been cremated since the disaster struck, with each cause of death being reported as “natural causes”. Economic damages have been estimated between US$45 billion to $US95 billion, a major blow to Puerto Rico’s already ailing economy.

But beyond the quantifiable losses, Orta-Rivera also describes a state of deep emotional and psychological trauma within the Puerto Rican community.

“We have never experienced a category 4 or 5 hurricane. Our minds were filled with ‘what ifs’,” she said.

She herself experienced emotional stress so severe that it manifested physically. “My period stopped when it already started,” she said.

Orta-Rivera also had an asthma attack, something that she last remembered occurring to her in her childhood.

“I have never felt asthma caused by emotions,” she said.

Others were having panic attacks. A day before the hurricane struck, Orta-Rivera was telling her mother how strong the hurricane was going to be and the possible damages to the island.

“I remember she told me, “Amy, please stop telling me all this,” and as soon I turned my head to see her, she already was crying inconsolably. I asked her, what was happening to her, and she told me that I must go to the hospital because she was having a panic attack.”

The mental health fall-out of the devastating hurricane isn’t an isolated incident.

Increasingly, health experts are also looking at an unseen toll disasters have on the psyche of people, including those working directly with disasters and climate impacts worldwide.

“

I knew things were going to be bad, but not like this. It feels like we are never going to recover.

Amy Orta-Rivera, resident, Gurabo, Puerto Rico

A report launched in March 2017 by the American Psychological Association (APA) and ecoAmerica, a US non-profit that builds public support and institutional leadership for climate awareness and solutions, confirms the reality of climate change impacts on mental and physical health.

According to the report titled “Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications and Guidance,” climate change has acute and chronic impacts, directly and indirectly, on individual well-being.

Climate change-induced disasters have the potential to cause immediate and severe psychological trauma, which can manifest in the form of anxiety, phobia, depression, and alcohol and drug abuse, among other things, the report said.

Extreme events resulting from climate change can also leave people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PSTD). For instance, the report found that among a sample of people living in areas affected by the 2005 Hurricane Katrina, one in six people met the criteria for PTSD and 49 per cent of people developed an anxiety or mood disorder.

A bridge in the neighborhood of Navarro in Gurabo, Puerto Rico. September 21, 2017. Image: Amy Orta-Rivera

“

The interlinked problems within climate change can hook us emotionally and intellectually.

Thomas Doherty, clinical psychologist, American Pyschological Association

Climate trauma among climate professionals

Climate trauma also occurs among professionals who grapple with the immensity of the climate change issue in their everyday work, say experts.

Clinical psychologist Dr. Thomas Doherty, based in Portland Oregon and who was featured in the report, said that the interlinked problems within climate change, such as poverty, inequality, loss of homes and cherished places, species extinctions, and threats to people’s well-being and livelihood “can hook us emotionally and intellectually”.

“These issues lead to feelings of curiosity and insight as well as fatigue and despair,” he said.

Doherty has counseled professionals experiencing varying crises of meaning and responsibility in the course of their work on climate change. These include: A scientist who has sailed in the Pacific garbage patch, an environment engineer who has run the numbers and doesn’t see a way to effectively address carbon emissions, and a ranger in the Glacier National Park who has witnessed rapid ice melt.

Orta-Rivera works as Project Associate for the San Juan Bay Estuary Program of AmeriCorps Vista, a US federal agency that delivers services to poor communities, including disaster preparedness and response. She also reported having experienced mental and emotional trauma at the height of Maria’s fury.

“It is extremely difficult to go to a community and know that someone is thinking about suicide because they have lost their home and they are not receiving any help. In moments like this, you have to stop whatever you are doing, listen to the person and guide them where the resources are,” she said.

A way to mentally cope with disaster

Doherty believes that to mitigate against the physical and mental health risks of disasters, individuals and communities must proactively anticipate climate impacts and take concrete adaptation actions.

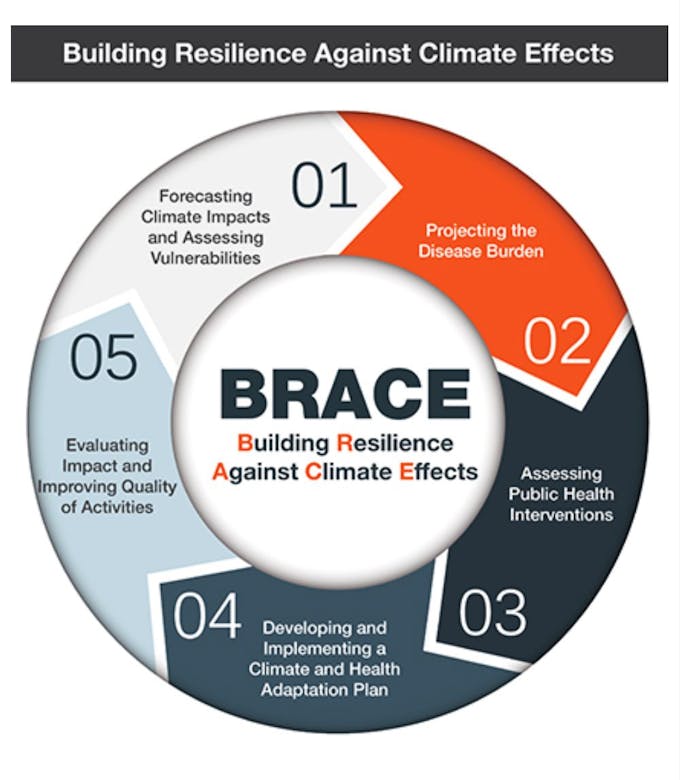

He echoes the recommendations of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) framework on Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) . The framework offers health officials and community leaders a practical guide to develop a public health plan and response program based on climate data.

BRACE framework. Image: CDC

CDC’s BRACE framework recommends understanding the health-related climate impacts people might sustain, identifying the most vulnerable communities and where they are located, and estimating additional health issues that may occur in the future.

“The BRACE model can help communities seeking to become more resilient by anticipating local health or economic impacts, identifying vulnerable groups that need protection, and proactively implementing a community-wide adaptation plan that can be reevaluated as more becomes known about changing local conditions,” Doherty said.

As Puerto Rico continues to wait for urgently-needed relief and rebuilding assistance, Orta-Rivera lays blame for much of the devastation on politicians who have long delayed the urgent and important mandate to tackle climate change.“Many urban planners warned the government not to build on flooding areas, or that we need a better electrical infrastructure. Sadly, for many years politicians have allowed these practices and now people, especially low-income communities, are facing the consequences of these decisions,” she said.

Despite political inaction, Orta-Rivera is determined to educate people about climate change and to help them recover from the disaster.

She also offers words of advice for fellow professionals in the field of climate and disaster relief work on how to better cope with climate trauma.

“Recognise when we need to step back, even if it is for a minute to be alone and cry, or even to look for help. Do something good, even if it is for just one person, it will lift your spirit and make you stronger again so you can continue your work helping to tackle climate change,” she said.