The risk of severe forest fires in Indonesia that choke much of Southeast Asia annually with toxic “haze” smoke is believed to be moderate this year, with wetter weather reducing the threat of one of the region’s biggest sources of air pollution and carbon emissions, according to experts.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The dry season that typically runs from April to October in Indonesia has been relatively mild so far this year, with some projections suggesting that 2020 could be a La Niña year, with a cooler Pacific Ocean leading to more rain in Asia, according to the 2020 Haze Outlook report from the Singapore Institute of International Affairs (SIIA), a thinktank.

Though the risk of severe transboundary haze that affects much of the region—as it did last year, when Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Thailand, and Vietnam, the Philippines, were affected by smog from burning Indonesian forests—is not high, some haze is almost inevitable. Haze events have been an almost annual occurence since the intensification of industrial agriculture in Indonesia more than 40 years ago.

Weather conditions usually have the biggest influence over the severity of haze outbreak. This year, though, the Covid-19 pandemic, which has hit Indonesia as hard as anywhere in Asia, presents an additional fire threat.

Measures to defend against the virus are making land-use monitoring and the enforcement of laws that prohibit starting fires difficult. Despite depressed prices of commodities such as oil palm, paper and rubber, the economic pressure on growers to open up more land for development could increase the chances of haze, the report said.

Smaller growers and medium-sized companies focused on the domestic market, which places a smaller premium on sustainable practices, will be the most likely cause of the fires this year, while larger companies have highly-scrutinised sustainability commitments they must stick to, and have “expended effort” to prevent and effectively suppress fires on the ground, the report said.

“The big companies have scale and resilience, and can wait out the situation. The danger is companies with lower margins, which might see the need to continue burning even though the market [for commodities] is weak,” said SIIA chairman Professor Simon Tay.

Even so, the social programmes run by the big firms to persuade villages in their concessions to stay fire-free with cash rewards will prove difficult to sustain during this year’s dry season. “Companies are taking the programmes online, but internet access [in remove plantation areas] is not reliable, and Zoom engagement is not the same as face-to-face,” noted Aaron Choo, SIIA’s assistant director, international affairs and digital media.

Assigning responsiblity for the fires is a contentious issue that coronavirus measures will make even trickier, as on-the-ground verification efforts will be much reduced. However, it was pointed out in a webinar held by Asia Pulp and Paper (APP), Indonesia’s largest pulpwood firm, that 69 per cent of last year’s fires occurred outside of land belonging to the big companies, according to August-September 2019 data from World Resources Institute.

“Managed concessions must be doing something right [to reduce fires],” noted Bernard Tan, Singapore president of Sinar Mas, owner of APP, during the session titled Behind the Flames.

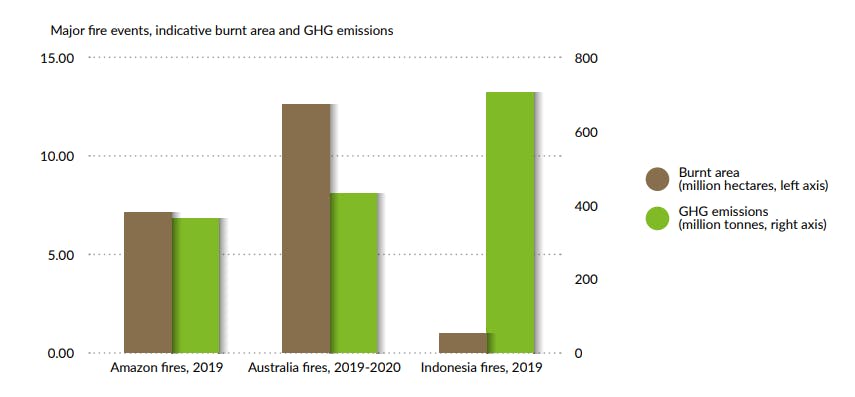

In 2019, Indonesia’s forest fires, which are typically caused by slash-and-burn techniques to quickly and cheaply prepare land for planting, emitted more carbon than the Australian bush fires of 2019/2020 and the 2019 Amazonian fires in Brazil. The emissions of Indonesia’s fires are particularly high when they occur on carbon-rich peatlands. Peatland fires are by far Indonesia’s biggest source of carbon emissions—even outstripping energy in a country that sources two-thirds of its power from coal.

The carbon emissions of Indonesia’s peatland forest fires in 2019 compared to the Australian bush fires of 2019/2020 and the Amazonian forest fires in Brazil in 2019. Data: Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS). Source: Singapore Institute of International Affairs Haze Outlook Report 2020

Blame game

Larger palm oil and pulp and paper companies have shouldered much of the blame for the haze in the past, as it is these companies that have historically drained the peatlands on a massive scale, leaving them chronically vulnerable to fires in the dry season. These companies also continue to operate on peat soil. APP products were stripped from supermarket shelves in Singapore in 2015, one of the most severe haze years on record, when it emerged that some of the worst fires were on the firm’s land in South Sumatra.

“Had the SIIA report focused on the operations of Indonesia’s large pulp companies, rather than their sustainability rhetoric, it may have reached a different conclusion about their ongoing risk for future haze episodes in Singapore,” commented Brian Orland, an analyst at Woods & Wayside International, an environmental non-profit.

“Since the catastrophic fires of 2015, both APP and Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) have expanded in ways that compound pressures on peatlands, even as they claim the opposite. Both companies continue to grow over one-half their pulpwood in plantations developed on drained peatlands, which can create highly incendiary conditions,” he said.

Orland said that until APP and APRIL reduce their dependence on peat plantations, their operations will continue to pose significant risks for the region’s health and economy, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as climate change.

The bigger firms often control smaller entities through opaque, byzantine ownership structures that make tracing the real culprits difficult. Choo of SIIA pointed out that while Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry has taken some companies to court over the fires, fines have rarely been issued or collected. Since 2015, the Indonesian government has won US$223 million in judgments against land-burning plantation firms, but collected just US$5.5 million.

New legislation could make punishing the culprits even more difficult, noted Kiki Taufik, project leader, Indonesia forests campaign, for environmental group Greenpeace. Though the coronavirus has slowed its introduction down, an omnibus bill submitted in February could mean reduced liabilities for companies caught with fires on their concessions.

Effective restoration?

The effectiveness of a government agency set up to restore areas of peatland devastated by the 2015 fires and reduce incidences of fire is another question mark hanging over the 2020 dry season. While the Peatland Restoration Agency (Badan Restorasi Gambut, or BRG) has restored its targeted area outside of company concessions, progress on restoring land inside concessions has been much slower.

As of last year, only about 18 per cent of targeted restoration area within concessions had been restored, SIIA’s report noted. “Some companies are forthcoming [about BRG restoring peatlands on their land], some are not,” commented Tay, adding that tracking BRG’s progress has been hard over the last few months, because of Covid-19 restrictions.

But BRG’s future is unclear. While Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo, reportedly wants to renew the agency’s mandate, that has yet to be officially confirmed. “Even if the BRG’s operating period is extended, it remains to be seen how much funding it will receive post-2020” give the impact of the virus on the economy, SIIA’s report said.

Environmentalists also fret about the solidity of other government forest protection programmes, including a ban on the issuance of plantation permits in primary and peat forests, and a three-year ban on new palm oil permits. Meanwhile, a study by WWF, released in May, showed that Indonesia’s deforestation rate, which had slowed since 2015, has climbed again in the first three months of 2020.

The green group said that there is evidence to suggest that illegal loggers have taken advantage of physical distancing measures that have scaled back forest patrols.