Larry Fink’s annual letter to the finance industry has become a highly-anticipated event for investors in recent years.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

After all, Fink heads BlackRock, the largest money manager in the world overseeing over US$8 trillion in assets. It probably helps that he had a veteran speechwriter who was chief writer for the former United States Treasury Secretary during the financial crisis to hone the messaging in these influential letters.

Fink’s letters – known for aphorisms like “climate risk is investment risk” and “purpose is the engine of long-term profitability” – have helped popularise the once niche area of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing.

But he has also sparked an anti-ESG movement, which reached fever pitch most recently when President Joe Biden issued his first ever veto to reject a Republican proposal that would have prevented retirement fund managers from considering ESG principles when making investment decisions.

For now, the politicisation of ESG seems contained in the US, though investors in Asia have expressed that they expect more political pressure against ESG investing in the future.

The recent backlash has led to some high-profile exits from climate-focused alliances. Last year, BlackRock’s biggest rival Vanguard withdrew from the Net Zero Asset Managers, a coalition of companies committed to net-zero emissions by 2050.

Just last month, insurer Munich Re announced its withdrawal from a related coalition, the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance, citing antitrust risk – another point of contention Republican politicians have with financial institutions collaborating over ESG concerns.

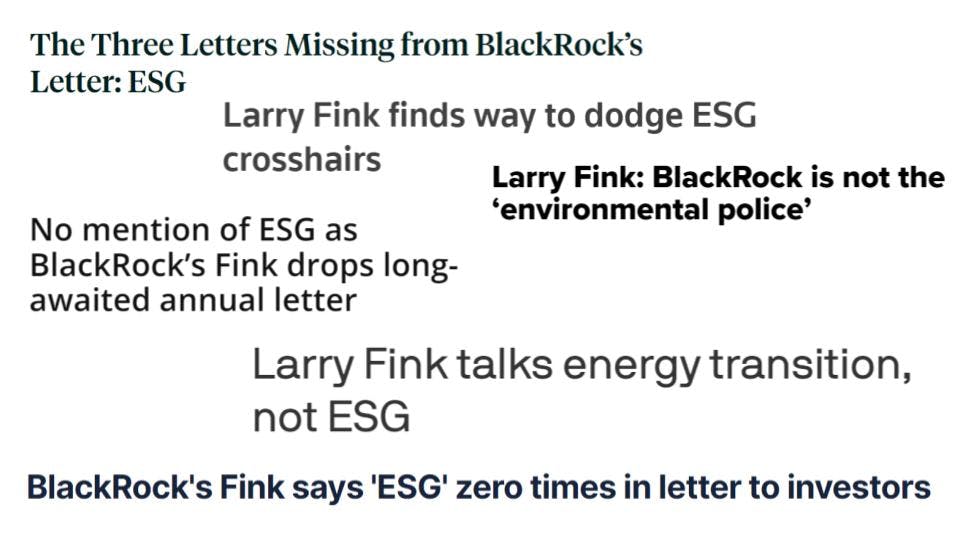

This was why Fink’s slience on the three-letter acronym in his latest 9,000-word missive was what made major news headlines this year.

Headlines from various media outlets covering BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s 2023 annual letter. Sources: Barron’s, Reuters, CNBC, Responsible Investor, Axios, ETF Stream

Eco-Business traces the rise and fall of ESG through Larry Fink’s letters over the past decade:

2012-2015: Pre-ESG era

Fink sent his first “Dear CEO” letter in 2012, which laid out how the firm’s approach to corporate governance – touted as “value-focused engagement” – differed from that of other US investors of that time.

Up until then, shareholders often voted according to the Institutional Shareholder Service (ISS), the shareholder advisory firm that recommends how shareholders should vote on executive pay and corporate directors at annual meetings.

“We reach our voting decisions independently of proxy advisory firms on the basis of guidelines that reflect our perspective as a fiduciary investor with responsibilities to protect the economic interests of our clients,” declared Fink.

Michelle Edkins, who was hired as the global head of corporate governance in 2011, raised her frustration over the lack of active engagement US companies had with long-term shareholders like BlackRock in a 11 June meeting where top managers, including Fink, were present.

“Companies wait until the eleventh hour to come to us or they assume we are going to follow ISS,” Edkins recounted what she told the group to the New York Times.

The meeting led Fink to write his epochal letter to corporate America. During the 2012 proxy season, the period between April to June where many companies hold annual general meetings, BlackRock voted its clients’ shares on 129,814 proposals at 14,872 shareholder meetings worldwide.

Fink’s subsequent letters in 2014 and 2015 continued to stress the importance of “good corporate governance” – the “G” aspect of ESG – to achieve long-term returns, and urged companies in which BlackRock held significant investments to engage with it on issues of corporate governance.

2016: Emergence of ESG

Just the year before, guidance from the US Labour Department – the rule Republicans tried to overturn years later – announced that pension fund fiduciaries can consider ESG factors in their investment decisions without fear of repercussions, as long as they are not accepting lower returns or greater risks.

The Paris Agreement, in which countries agreed to keep global warming from exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius, was also adopted at international climate conference COP21 just two months prior.

All these developments allowed Fink to boldly proclaim in his 2016 letter, “Generating sustainable returns over time requires a sharper focus not only on governance, but also on environmental and social factors facing companies today.”

“At companies where ESG issues are handled well, they are often a signal of operational excellence,” he wrote.

The acronym was mentioned five times, making it the second-most mentioned word after “long-term” – a perennial theme in Fink’s letters – which was mentioned 28 times.

This also marked the beginning of heightened scrutiny of BlackRock’s own record on environmental and social issues. Later that year, the firm’s shareholders criticised its “consistent votes against virtually all climate-related resolutions”.

“BlackRock’s voting practices, which appear inconsistent with company statements to companies and internal policies addressing climate change, pose reputational risk for the company,” the shareholders asserted.

2017: Continued endorsement of ESG

Fink acknowledged in his 2017 letter that the many assumptions business plans were based on had been upended by the exit of the United Kingdom from the European Union, the upheaval in the Middle East, and the unexpected election of Donald Trump as US President.

Former US President Donald Trump and BlackRock CEO Larry Fink at the White House on 3 February, 2017. Image: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Fink urged companies to adapt their strategies “not just following a year like 2016, but as a part of a constant process of understanding the landscape in which [they] operate,” and segued to his plug for ESG three paragraphs later.

“ESG factors relevant to a company’s business can provide essential insights into management effectiveness and thus a company’s long-term prospects,” wrote Fink.

While BlackRock cannot divest from companies held in index-linked investments – which makes up the bulk of client’s holdings – it warned, “we do not hesitate to exercise our right to vote against incumbent directors” if insuffient progress was being made.

In that year’s proxy season, BlackRock and Vanguard voted to back shareholder proposals on climate-related issues for the very first time. Their votes helped to push through resolutions at ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum demanding for the oil producers to report climate-related risks.

Incidentally, the day after this historic vote at Exxon’s shareholder meeting, Trump announced he would pull the US out from the Paris climate accord.

2018: ESG thought leader

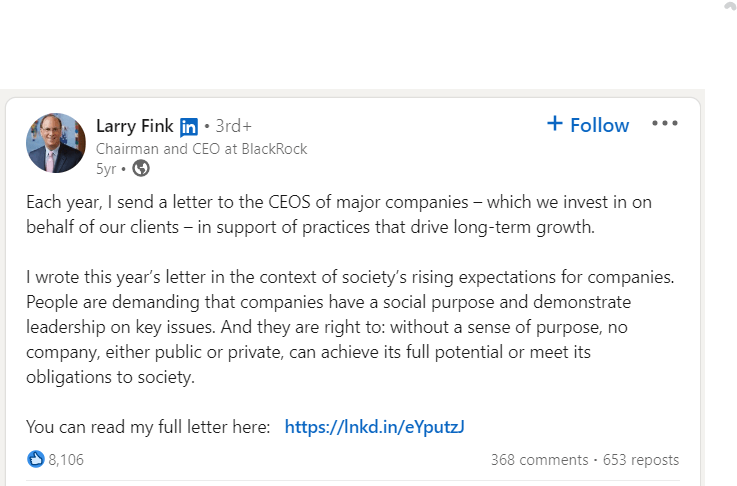

Larry Fink’s 2018 letter generated significantly more reaction than the ones before, and was liked on LinkedIn over 8,000 times.

This letter cemented Fink’s leadership on ESG investing and was covered by global media outlets, including New York Times and Wall Street Journal for the first time.

Titled “A Sense of Purpose”, the letter focused on the “S” in ESG, and insisted that companies must “serve a social purpose” and make “a positive contribution to society” to prosper over time.

While these sentiments were not new, what was new was that they were being uttered by the world’s biggest money manager, which led some to hail Fink as the “new conscience of Wall Street”.

“A company’s ability to manage environmental, social, and governance matters demonstrates the leadership and good governance that is so essential to sustainable growth, which is why we are increasingly integrating these issues into our investment process,” Fink wrote.

But not everyone was impressed by Fink’s high-minded sentiment. Billionaire investor Sam Zell quipped in an interview with CNBC, “I didn’t know Larry Fink had been made God.”

Zell also questioned BlackRock’s ability to influence change in corporations since a large proportion of the firm’s assets are in passive index funds, which hold stocks in the same proportion as market indices they track, instead of picking stocks that could outperform others in the indices. “Either they’re a passive fund that follows the market or they’re a leader that’s setting the tone,” he said.

Later that year, global environmental groups, including 350.org and Greenpeace, launched a campaign called “BlackRock’s Big Problem” to press the firm to shift investments away from polluting sectors towards climate solutions. In its letter to Fink, the group wrote that BlackRock’s efforts in considering environmental and social factors were headed in the right direction, but “fall well short of what is required.”

2019: ESG for profits

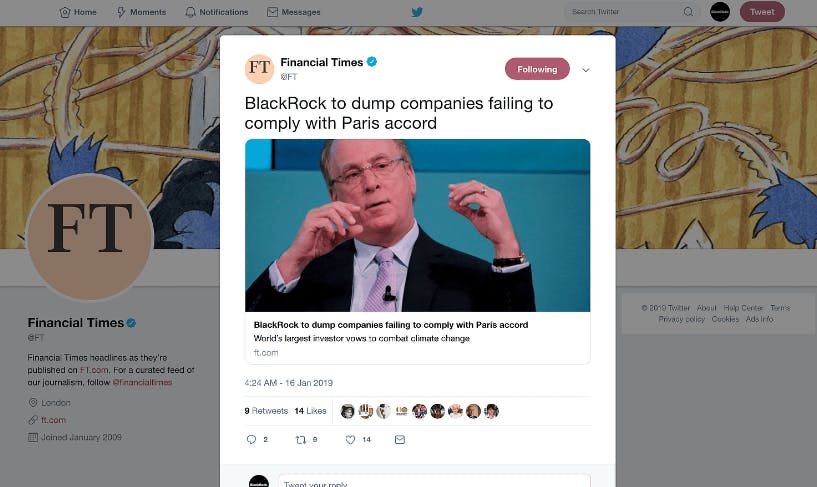

The fake letter sent out by activist group Yes Men pretending to be Larry Fink was covered by The Financial Times and went viral on Twitter, before being revealed as a hoax. Image: Yes Men

Fink’s annual letter and association with ESG investing had become such a fixture that a group of activist pranksters posing as him sent out a spoof letter the day before the release of the actual letter.

The bogus letter entitled “Purpose in Action” announced that BlackRock would divest from coal companies in all its actively-managed funds and vote only in favour of management when they worked towards net-zero emissions by 2050.

In anticipation of Fink’s 2019 letter, shareholder advocacy groups like ShareAction and ClientEarth also called on BlackRock to close the gap between rhetoric and climate action and to support more shareholder climate resolutions in the coming proxy season.

Fink’s actual letter titled “Purpose and Profit” clarified that he is not downplaying the importance of profits, even while pushing companies to address societal issues. “Purpose is not the sole pursuit of profits but the animating force for achieving them,” he wrote.

Fink also urged companies to fill the leadership vacuum to tackle environmental challenges, gender and racial inequality, as well as the retirement crisis, given that the world’s leading democracies “have descended into wrenching political dysfunction”.

ESG issues will be “increasingly material to corporate valuations” as wealth shifts to a new generation with different investment preferences, Fink maintained.

2020: ESG will fundamentally reshape finance

Fink’s 2020 letter went heavy on the “E” of ESG. “Climate risk is investment risk,” the very first subheading read.

It referenced a separate letter he had written to BlackRock’s clients that day, which announced that the company would exit investments in thermal coal producers and launch new funds that exclude fossil fuels (incidentally, bearing resemblance to the “updates” in the fake 2019 CEO letter).

Fink recognised that climate change presented a “more structural, long-term crisis” than any other financial crises he had witnessed in the previous four decades, and cautioned that “companies, investors, and governments must prepare for a significant reallocation of capital.”

He also warned that companies that fail to disclose their net-zero transition plans using frameworks like the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) would lead BlackRock to “increasingly conclude that companies are not adequately managing risk”, and could move the asset manager to vote against the management teams.

Just a month before, BlackRock had been accused by billionaire hedge fund manager Christopher Hohn of greenwash for not requiring emissions disclosures from firms it was invested in.

2021: ESG investing accelerates

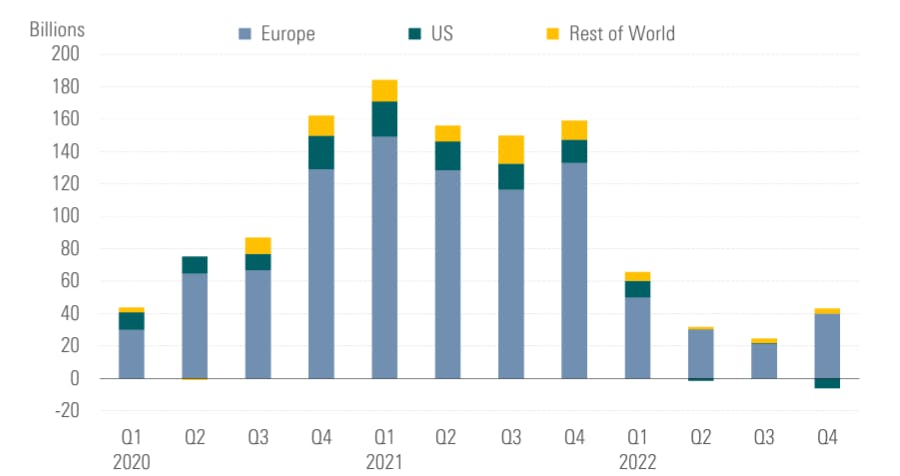

Global flows into sustainable funds peaked in 2021′s first quarter. Source: Morningstar Direct (as of December 2022)

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic roiling global markets, investment flows into ESG assets surged and hit a record high. Even Fink conceded that his prediction the year before of “a fundamental reshaping of finance” came to pass “faster than [he had] anticipated”.

Fink’s bet on the profitability of ESG investing also appeared to have paid off. “Over the course of 2020, we have seen how purposeful companies, with better ESG profiles, have outperformed their peers,” he wrote in his 2021 letter.

Fink once again urged companies “to disclose a plan for how their business model will be compatible with a net zero economy” and aligned with the Paris climate accords – which the US committed to rejoin the previous week, under President Biden’s new administration.

“I urge companies to move quickly to issue them rather than waiting for regulators to impose them,” Fink wrote, alluding to the launch of the International Sustainability Standards Board at COP26 just months prior, which aimed to give companies a unified framework for sustainability reporting.

Fink announced that BlackRock would implement a “heightened-scrutiny model” in its active portfolios, which included potentially exiting holdings that posed significant climate risk.

Climate activists from Stop the Money Pipeline holding a rally in midtown Manhattan on April 17, 2021 at the headquarters of BlackRock and J.P. Morgan Chase. Image: Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images

But in a report published earlier that month, activist groups Reclaim Finance and Urgewald exposed that BlackRock still held US$85 billion in coal-related assets, and that investments in sustainable assets only accounted for 3 per cent of its exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

2022: Defending ESG – not “woke”

In his 3,300-word letter – the longest he had written to date – Fink defended BlackRock against attacks from right-wing officials in the US calling its approach to ESG investing “woke”.

“We focus on sustainability not because we’re environmentalists, but because we are capitalists and fiduciaries to our clients,” Fink wrote in his 2022 letter entitled “The Power of Capitalism”.

Fink also emphasised that businesses like BlackRock focus on climate-related issues not because they are the “climate police”, but simply because it makes financial sense. “Stakeholder capitalism is not about politics. It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not ‘woke.’ It is capitalism,” he asserted.

Tariq Fancy, who served as BlackRock’s first chief investment officer for sustainable investing between 2018 and 2019, has called Fink an “emperor with no clothes” for “ducking the fight” on ESG. Image: Tariq Fancy

Separately the year before, former BlackRock sustainable investing chief Tariq Fancy called out ESG investing for being a “dangerous placebo that harms the public interest”.

Fancy pointed out that financial institutions like BlackRock have an obvious profit motive to push ESG products since they generally have higher fees than non-ESG products. But it was “not totally clear if they create much positive environmental impact.”

In response to criticism that BlackRock had failed to reduce its exposure to high carbon-emitting companies, Fink argued, “Divesting from entire sectors – or simply passing carbon-intensive assets from public markets to private markets – will not get the world to net zero.”

Fink also clarified that BlackRock “does not pursue divestment from oil and gas companies as a policy”, in what seemed to be veiled response to Texas lawmakers who passed a law the year before which could blacklist asset managers that allegedly “boycott” fossil fuels.

2023: Sidestepping the ESG debate

For the first time since the dawn of ESG in Fink’s annual letters, the three-letter abbreviation was absent.

Instead, Fink started and ended his longest letter to date by drawing attention to the firm’s performance in the past year. “We are proud to be the highest-performing financial services stock in the S&P 500 since our IPO in 1999, delivering a total return of 7,700 per cent,” he wrote, which appeared to counter Republican accusations that ESG requires sacrificing financial returns.

“Since BlackRock’s founding, we have always been unwavering in our commitment to serving our clients, and by doing so, we have delivered outsized returns for our shareholders,” reminded Fink.

Despite the glaring omission of ESG, Fink did not back away from climate concerns. “For years now, we have viewed climate risk as an investment risk. That’s still the case,” he asserted.

Fink highlighted growing investment opportunities in the energy transition – dubbed transition finance – especially with the Inflation Reduction Act in the US and similar incentives being developed in Europe.

But the term “transition” only surfaced in paragraph 19 and the word “climate” is mentioned just five times in the bottom half of his lengthy letter.

Additionally, Fink downplayed the role that businesses should play in shaping the transition. “It is not the role of an asset manager like BlackRock to engineer a particular outcome in the economy, and we don’t know the ultimate path and timing of the transition,” he wrote.

This stood in contrast with Fink’s 2020 letter, which read: “BlackRock does not see itself as a passive observer in the low-carbon transition. We believe we have a significant responsibility — as a provider of index funds, as a fiduciary, and as a member of society — to play a constructive role in the transition.”

Furthermore, Fink signaled that BlackRock would take a more hands-off approach to proxy voting compared to previous years as it increasingly allows clients to directly decide how they want their shares to be voted with its Voting Choice programme.

However, global coalition BlackRock’s Big Problem has cautioned against this messaging over consumer choice. “BlackRock is leaning into offering clients choice, but deference to choice can’t be a shield for abdication of responsible risk management,” said Jessye Waxman, a senior campaign representative at Sierra Club which is a partner of the network.