Southeast Asia could see more funding in nuclear power, following the European Union’s (EU) proposal to include the energy source in their green finance guide, according to analysts.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

More Asian countries may also consider including nuclear energy in sustainable investment frameworks, analysts told Eco-Business, but doubt that these developments will significantly help to hit net-zero 2050 targets, citing cost, technological hurdles and competition with other fuels.

The EU released a draft of its green finance taxonomy on 31 December, which defines what projects can be classed as green to pique the interest of investors.

The bloc said that natural gas projects should count as sustainable under certain conditions. Nuclear energy projects that promise to manage radioactive waste, also got listed amid controversy. Environmental groups and countries like Germany and Austria slammed the plans with the former closing half its remaining nuclear power plants as part of the country’s phase-out of nuclear energy.

France and several central European states that rely on nuclear power support the move to class nuclear as a sustainable investment.

Beni Suryadi from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Centre for Energy said the EU’s proposal, if passed later this month, could stimulate investment in nuclear power projects in Southeast Asia.

“Governments and nuclear project developers would have higher confidence to invest and develop the projects,” Suryadi explained.

Several Southeast Asian countries have tinkled with research reactors, though none are operating commercial units. Vietnam had a development plan that fell through due to high costs; the Philippines has a plant which has never been switched on for safety and political reasons.

A 2018 ASEAN study stated that these countries, along with Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand, were aiming to use nuclear power by 2035, although Indonesia’s latest plan is to have one up and running by 2045 instead.

EU money could help to buoy Southeast Asia’s nuclear ambitions, according to Dr Philip Andrews-Speed, a senior principal fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Energy Studies Institute.

“If the banks buy into it, so that they and other sources of finance can wave their green credentials, then that will have some influence in Southeast Asia,” he said.

The EU’s proposed inclusion of natural gas and nuclear is likely to send a signal to markets in Asia, according to Elrika Hamdi, an energy finance analyst at United States think-tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. Southeast Asian countries may look to add nuclear power, and indeed gas, to its green investment rulebook.

“The EU’s green taxonomy has long been held as the gold standard,” she explained.

Currently, Asia’s green taxonomies have no consensus on nuclear power. ASEAN’s rulebook, released last November, provides a guide to analysing projects but does not specify any particular activity as green or not. It stated that nuclear energy could be given the nod if safety issues surrounding nuclear waste can be sorted. The ASEAN Centre for Energy considers nuclear power clean energy, citing its low carbon emissions being on par with wind energy.

South Korea, which gets almost a fifth of its power from nuclear energy, does not recognise it as green while liquefied natural gas was declared as a sustainable investment in plans announced on 30 December by the government.

China and Russia both endorse nuclear power in their green taxonomies.

Proponents of nuclear power say the energy source can replace fossil fuels to provide a steady flow of low-carbon electricity – something wind and sunlight struggle to achieve. Critics fear the lasting impact of both disasters and nuclear waste, a permanent solution for which largely does not exist.

Peter Godfrey, managing director for Asia Pacific at UK non-profit Energy Institute, agreed that more Asian countries may copy Europe in classifying investment in nuclear power development as green.

But he added that Asia still prefers natural gas as the “transition fuel” to replace heavily polluting coal, with no shortage of supply from domestic wells and the Middle East. Nuclear and gas might be left to compete for the same market space, with gas edging in the race as facilities are cheaper to build.

“I would suggest that post-Covid, and given other infrastructure priorities, nuclear power is not going to move terribly quickly,” said Godfrey.

Southeast Asian governments may not have the wealth to absorb cost overruns in nuclear power development, Hamdi said. Earlier research found that 97 per cent of nuclear power projects worldwide blew their budgets by over 100 per cent, or US$1 billion on average.

Uneven pace of Asia’s nuclear power development

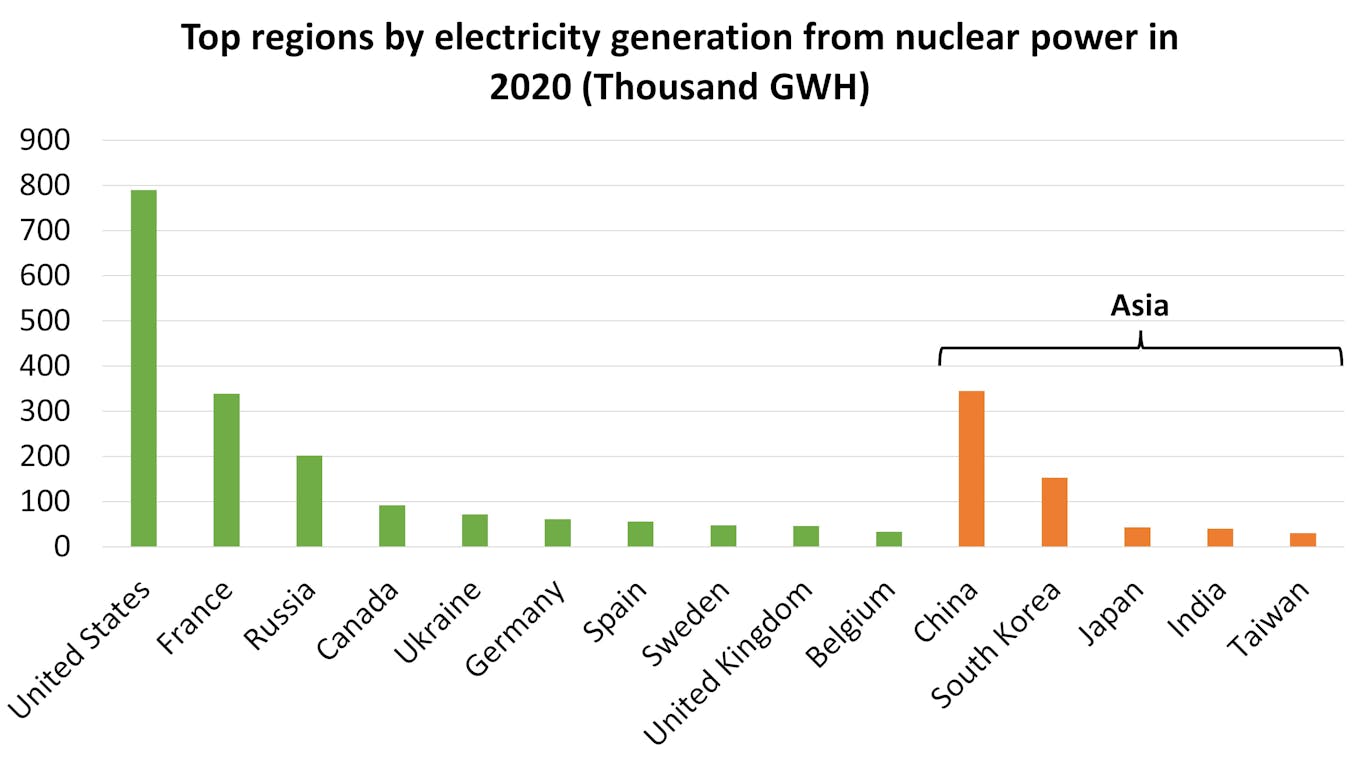

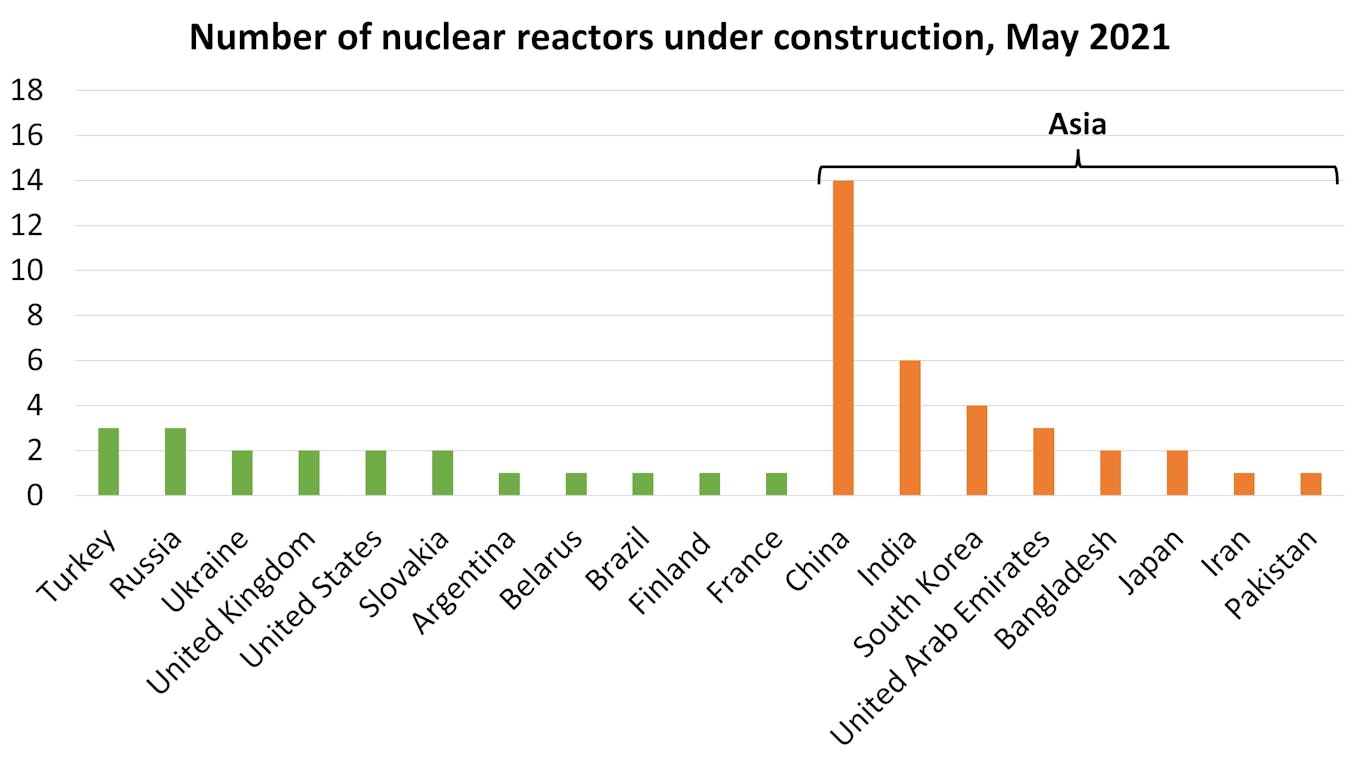

While the bulk of the existing nuclear power supply is in the West; Asia and the Middle East is leading in future developments.

China is ahead regionally in its development of nuclear power, with 50 completed reactors and as many being built or planned. It is aiming to run or have slated for development, 200 gigawatts of nuclear plant capacity by 2035. That’s four times its current nuclear output and 10 per cent of its total electricity generation.

Neighbouring India has 23 constructed units and 20 in the pipeline. Eight plants are under construction, with two of them started in the second half of 2021. The country wants to produce over 22 gigawatts of nuclear power by 2031, up from the current capacity of under 7 gigawatts.

The rest of Asia has staggered in its development of nuclear. South Korea wanted to phase out nuclear power in 2017 but has recently started to develop smaller research reactors, as experts deem it unfeasible for the country to decarbonise without nuclear. It also has four commercial reactors under construction.

Japan announced plans to reboot existing plants last October, a decade after the Fukushima nuclear disaster which has left several settlements around the crippled plant off-limits to this day. The country is currently building two units, totalling about 2.8 gigawatts.

As for Southeast Asia, Hamdi said the region has to reckon with geographical disadvantages. Island nations, Indonesia and the Philippines, favour small-scale distributed power generation over large nuclear plants, she said.

Legacy of disaster

Southeast Asia also sits on the Western circumference of the Pacific Ring of Fire, characterised by active volcanoes and regular earthquakes.

Andrews-Speed said such geological risks are well-studied and can be managed but governments will have to build a business case to overcome safety concerns.

“A real issue in public perception is how competent the governments are to regulate safety. Do they have the skills, the number of people and the authority?” said Andrews-Speed. His previous research found that delayed reporting of a 2012 nuclear plant blackout and falsification of safety tests in South Korea affected public confidence in the energy source.

A 2021 study based on 2018 surveys found that there was low public support for nuclear energy development in Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam – five Southeast Asian countries the study said had the financial means for nuclear plants. Thailand ranked lowest with 3 per cent support and Indonesia topped the group at 39 per cent.

The study also found that trust in scientists and business leaders were the most influential factors for the public to support nuclear power development.

Suryadi added that public fear of the technology itself is also a factor, in part because of events like the Fukushima disaster, which was caused by an earthquake and subsequent tsunami that flooded reactors and forced 150,000 people to evacuate. Remediation efforts could take another four decades.

“The misinformation of radiation and nuclear waste also causes irrational fear to grow among the public,” he said.

An ASEAN Centre for Energy report released in 2020 to address low public support for nuclear power wrote that nuclear waste is “neither particularly hazardous nor hard to manage relative to other toxic industrial waste”. It pointed to research for permanent waste storage solutions in Europe and North America.

New nuclear power technology is also being developed, with small modular reactors and a new crop of “Generation IV” plants promising safety and efficiency. One small modular unit is operating in Russia, while estimates put the commercialisation of Generation IV technology no earlier than 2030.

“That should make nuclear more acceptable from the point of view of cost, the point of view of safety of the operation, and from the point of view of having less or no dangerous waste to deal with,” said Andrews-Speed.

But he is not expecting breakneck progress, given that countries may take a decade from starting a nuclear programme to running a power plant.

In the International Energy Agency’s 2050 net-zero projection, nuclear power will make up a tenth of energy sources, while biofuels and renewables will make up about two-thirds of the mix.

“I think we’ll begin to see the beginning of a trend by 2050. But will it massively change the picture from where we are today? I doubt it very much,” Godfrey said of nuclear energy.

Hamdi added that Southeast Asia should look to spend money on renewable energy instead, as it is easier to deploy and has fewer safety issues.

As for nuclear? “There will still be capital for it, but don’t use it from green capital,” she said.