This story is part of our Decoding Sustainable Finance series, where we attempt to break down complex terminology surrounding the latest regulations and trends in sustainable finance.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Over half of the global economy, equivalent to approximately US$58 trillion, is moderately or highly dependent on nature, according to a recent analysis by professional services firm PwC. As a result, there is growing expectation among shareholders, regulators and customers for large corporates to disclose their reliance and impacts on nature, and to begin to address them.

At the United Nations COP15 summit last December, the landmark biodiversity agreement signed by world leaders to protect 30 per cent of the planet by 2030 included a target calling for large companies and financial institutions to “regularly monitor, assess, and transparently disclose their risks, dependencies and impacts on biodiversity”, in order to reduce their negative impacts while increasing their positive impacts over time.

“

It costs nothing to destroy a forest. It costs nothing to use as much water as you want, or to pollute. And therein lies the problem.”

David Craig, co-chair, TNFD

According to asset manager Robeco’s 2023 Global Climate Survey, an increasing number of investors said that biodiversity was important or central to their investment policy, and find the loss of nature as great a threat as climate change.

Yet, many companies are still in the early stages of integrating nature- and biodiversity-related considerations into their commitments and risk assessment frameworks.

Advocacy group ShareAction’s survey of the world’s largest asset managers in June this year found that while almost all of them now have a long-term net-zero target, only about a quarter of them had made commitments on deforestation. Furthermore, just two-fifths of asset managers surveyed said they monitored areas of biodiversity importance and even then, there was considerable variation in terms of which “key biodiversity areas” they monitored.

Only 27 per cent of the world’s largest asset managers surveyed by ShareAction made commitments to end deforestation. Not one had set any specific targets about the conversion of natural ecosystems, or to manage investment risks to biodiversity, that went beyond their deforestation commitments. Source: ShareAction’s 2023 Point of No Returns

This need for guidance has spurred several new global frameworks, the most notable being the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), which builds on the work of its climate-related counterpart and is set to become the new baseline standard for nature-related risk reporting. The framework has gained backing from large international corporations like Nestlé, HSBC and BlackRock, and its final version is expected to be released in September.

What are nature-related risks?

Nature-related risks are potential threats posed to companies and investors from their dependence and impacts on nature. TNFD has grouped them into three broad categories: physical risks, which arise when natural systems are compromised; transition risks, which result from the changing regulatory, technological, or societal landscape; and systemic risks, which stem from the breakdown of the entire system, such as when tipping points are reached.

For instance, the decline of natural pollinator species and coral bleaching are risks for agribusinesses that rely on bees to pollinate their crops and fisheries that rely on healthy coral reefs respectively. Corporations can also drive nature and biodiversity loss, which alongside changing societal expectations, could threaten to destabilise the basis of their operations.

The problem with the current financial system is that it assumes that the natural system is free, said TNFD co-chair David Craig. “It costs nothing to destroy a forest. It costs nothing to use as much water as you want, or to pollute. And therein lies the problem.”

TNFD will help businesses and the wider economy price in the detrimental financial impacts from nature degradation by reframing nature as a set of capital assets that provides “ecosystem services” to corporations. This is done by breaking nature down into four realms – ocean, freshwater, land and society – which are further broken down into 34 biomes (areas of land or water with distinct ecosystem services and characteristics).

By putting a value on nature-related risks, it is hoped that businesses and financial institutions using the TNFD framework will start reversing the current declines in biodiversity, also known as achieving “nature-positive” outcomes.

How do they differ from climate-related risks?

Nature loss and climate change are closely interrelated and can have mutually reinforcing effects. For instance, nature loss through deforestation – which reduces the amount of carbon sinks for sequestering greenhouse gas emissions – diminishes resilience to climate change, which in turn leads to higher temperatures and drives further loss of nature and biodiversity.

However, while nature- and climate-related risks are two sides of the same coin, they are not the same. Notably, nature-related risks are much more complex to identify and measure than climate-related risks.

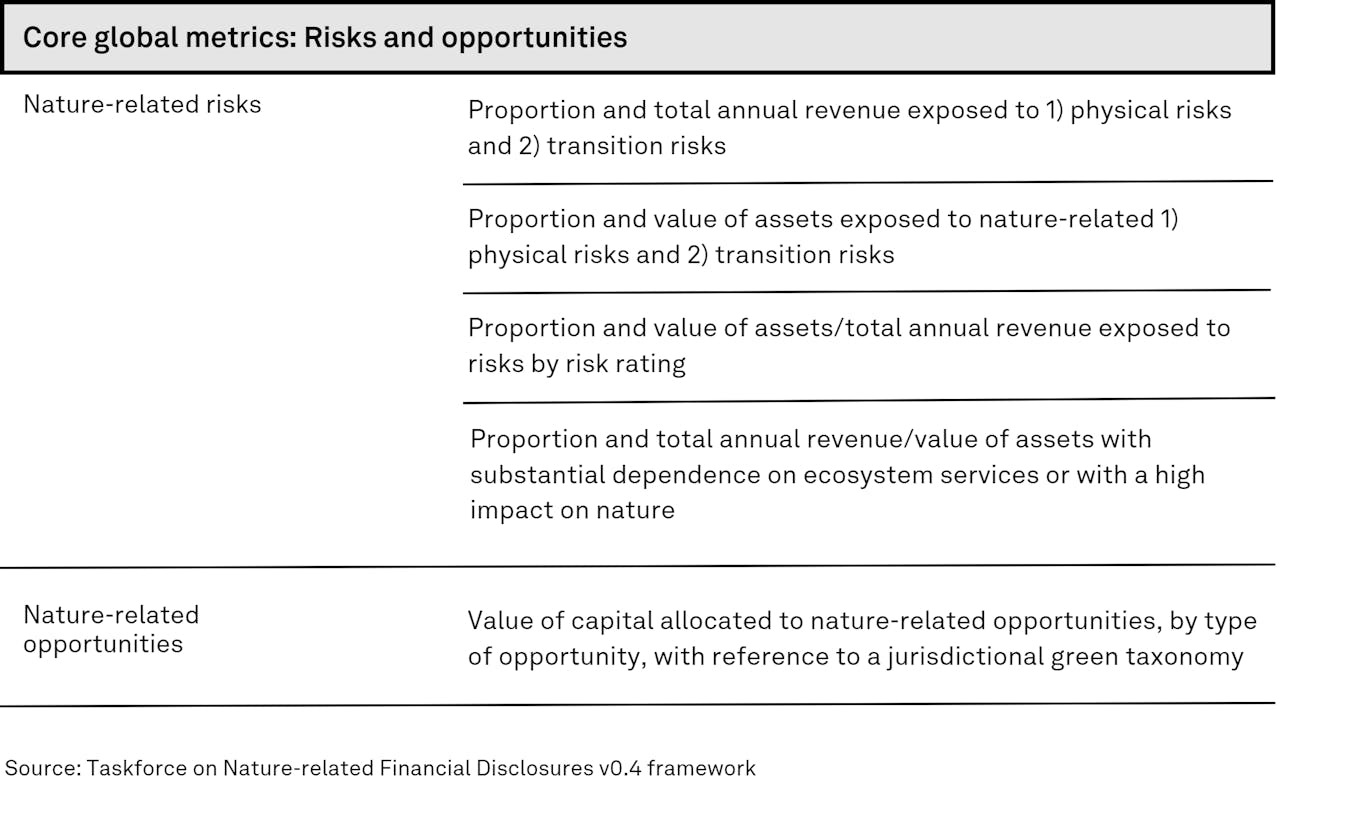

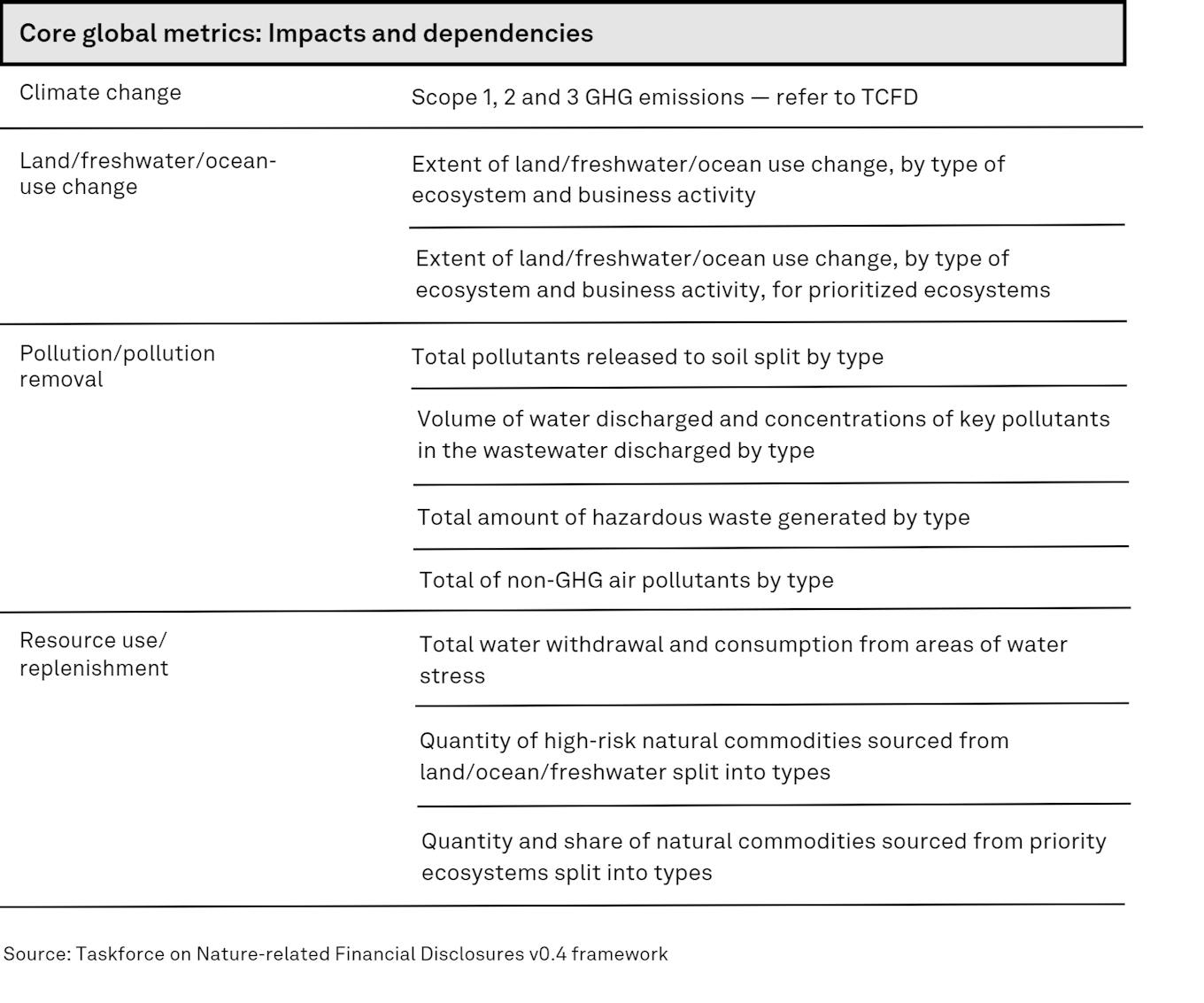

Unlike climate change, which can be measured using the standard metric of carbon dioxide equivalents no matter where you are in the world, nature loss is a lot more localised, with no single unit of comparison. TNFD’s framework includes 15 core disclosure metrics – five relating to risk and opportunities and 10 relating to impacts and dependencies – that apply globally and across sectors, excluding additional industry-specific disclosure metrics.

“In general nature-related risk is a new topic to organisations and feedback from the market has highlighted a need for the TNFD to go beyond development of disclosure recommendations to also develop ‘how-to’ guidance,” said Marianne Haahr, nature-related finance director of the data-driven non-profit Global Canopy, which is a founding partner of TNFD. This guidance takes the form of the LEAP four-phase approach of how to generate the information needed to disclose nature-related risks and opportunities, she said.

The LEAP approach – an integrated risk and opportunity assessment developed by TNFD – is short for Locate, Evaluate, Assess, Prepare. It provides companies with a step-by-step process to locate their interactions with nature, evaluate their dependencies and impact, assess their risks and opportunities, before responding and reporting on material nature-related risks.

The Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures framework’s five of 15 core disclosure metrics relating to risk and opportunities. Source: TNFD v0.4 framework

The Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures framework’s 10 of 15 core disclosure metrics relating to impacts and dependencies. Source: TNFD v0.4 framework

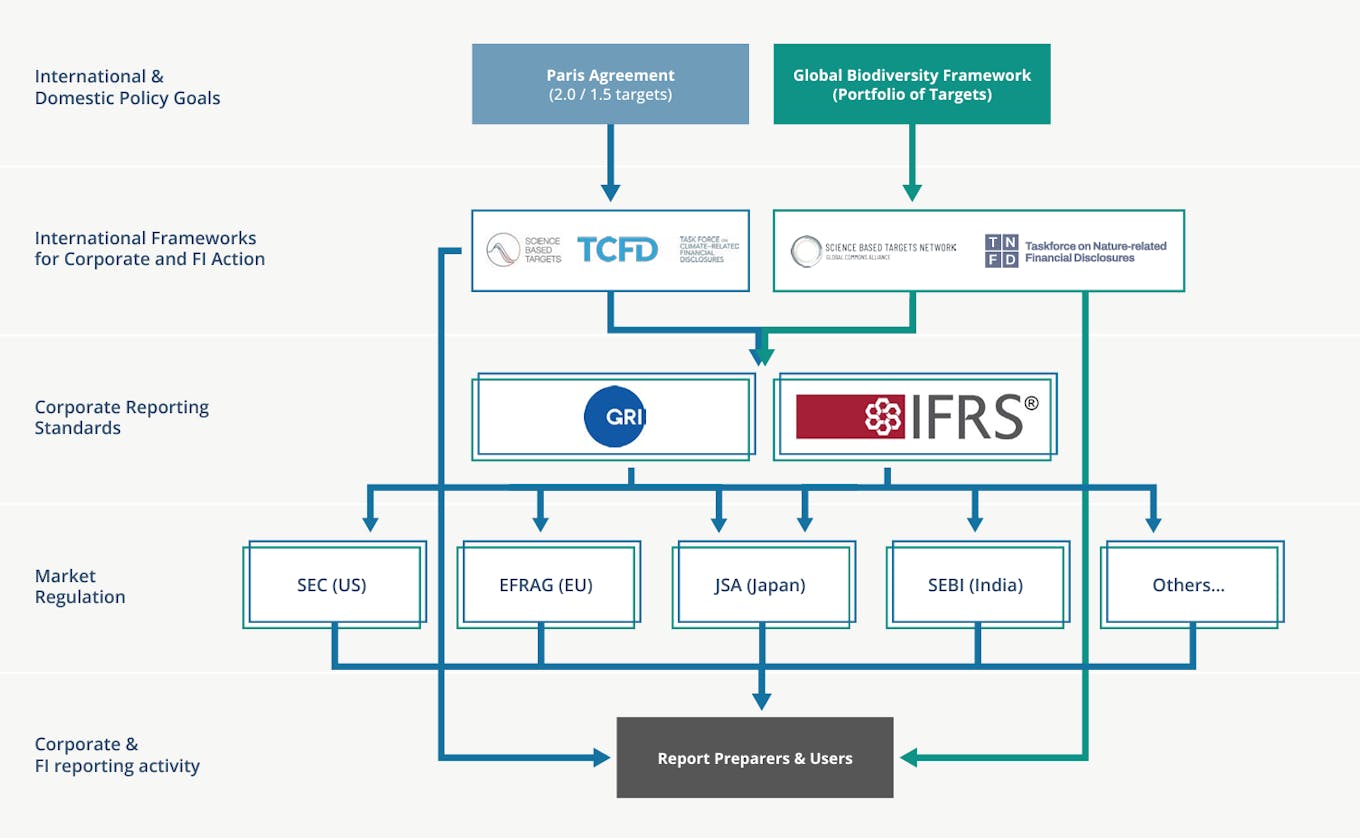

How does TNFD compare to other standards?

TCFD

The TNFD framework may look familiar to corporations that currently report using the Taskforce for Climate-related Disclosures (TCFD). The similarity is intentional.

“We reused as much of the TCFD framework as we possibly could – partly because of familiarity and to lower the friction of adoption, and partly because we see that climate and nature are issues that should be dealt with together,” said Craig.

The TNFD taskforce has retained the four pillars of TCFD recommendations – Governance, Strategy, Risk Management and Metrics and Targets – with Impact Management incorporated into Risk Management. It has also carried over all 11 TCFD recommended disclosures, to provide a consistent structure for reporting nature-related issues together with climate-related issues.

The notion of “scopes” in emissions reporting across the value chain has also been adapted to the nature context, where Scope 1 refers to direct operations, and Scope 3 refers to upstream, downstream and financed activities.

GRI and ISSB

Based on ongoing engagements with more than 200 businesses in Southeast Asia, Katia Bonga of the World Business Council for Sustainability Development (WBCSD) observed: “The strongest request (from companies) was for the framework to be consistent and as interoperable and complimentary as possible with other standards and guidelines, such as GRI and ISSB.”

Where the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures framework fits in the emerging reporting architecture. Source: TNFD v0.4 framework

As in traditional financial reporting, “materiality” in sustainability disclosures determines what a business should disclose to rest of the world. There are two main approaches companies can use to assess what is material to disclose: “single materiality” (or “financial materiality”), which is embodied in the newly launched International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards; or “double materiality”, which is applied in the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards that remains the most widely-used global sustainability reporting framework.

While the single materiality approach only considers the financial impacts of sustainability-related issues to a business, the double materiality approach also includes the firm’s impacts on the environment and society.

TNFD’s current framework allows varying approaches to materiality “to accommodate the preferences and regulatory requirements of report preparers and report users from organisations of all sizes and across all jurisdictions.”

On why TNFD has refrained to pick a side in this debate, Tony Golder, executive director of TNFD said in a recent interview: “If we pick one over the other, then we will limit the relevance and the attractiveness of the TNFD recommendations. We think that nature risk needs to be considered by everyone around the world.”

“We see the TNFD as a tool, we are not writing a standard,” said Golder, who added that the setting new regulatory standards like what governments do – take for instance Europe with the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) which has adopted a double materiality approach – is not the mandate of the taskforce.

How effective will TNFD be in protecting nature?

TNFD’s draft framework has been largely well received by market participants. Global Canopy’s Haahr said that the burgeoning nature-related metrics can be leveraged to design new types of products, like biodiversity-linked loans, which could be a new financing stream to reverse nature loss.

For example, Rabobank used existing data that farmers have been collecting for regulatory compliance purposes to launch a biodiversity-linked farmer credit in 2021 that rewards farmers in their loan book for lowering adverse nature-related impacts. Haahr also cited how the forthcoming European Union soil law “will further increase the data available” for these types of innovative nature-related transition financial products.

But some investor groups like ShareAction and UN Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI) have cited the need for a clearer definition of materiality and further guidance on how to apply materiality across the framework. ShareAction also recommended that TNFD clarifies that companies should be prepared to disclose all the information collected through the LEAP approch – as the draft framework specifies that not all information needs to be disclosed – should its stakeholders clarify that this information is material.

Separately, civil society groups have raised concerns that TNFD risks facilitating greenwashing. In an open letter to the TNFD, 62 non-governmental organisations – including BankTrack, Greenpeace and Rainforest Action Network, organised by Forests and Finance – said that TNFD’s work is “undermining real solutions to the nature crisis”, notably the work of Indigenous people and environmental defenders on the frontlines.

The coalition asserted that TNFD had failed to include diverse voices in the decision-making process as well as propose disclosures on links to violations of rights, lobbying against laws that help protect nature, and nature-related complaints against companies.

“Under the TNFD’s proposed framework, corporate ‘disclosures’ on biodiversity won’t apply if a company is facing allegations of environmental destruction, if it is lobbying against new laws to protect nature or if it is dramatically scaling up how much land it is using. Already we can see the TNFD’s work being championed in ways that distract from, and undermine, the real solutions to the biodiversity crisis,” said Shona Hawkes, advisor, Rainforest Action Network.

A TNFD spokesperson has responded to the claims in the open letter, saying that they have engaged directly with civil society organisations and listened carefully to their views. “In many cases their feedback and expertise on these issues has influenced the shape of the TNFD’s approach and final draft recommendations,” TNFD said.

What else is needed to support Asia’s green transition? Find out more at Unlocking Capital For Sustainability, our annual flagship event.