What is deep-sea mining?

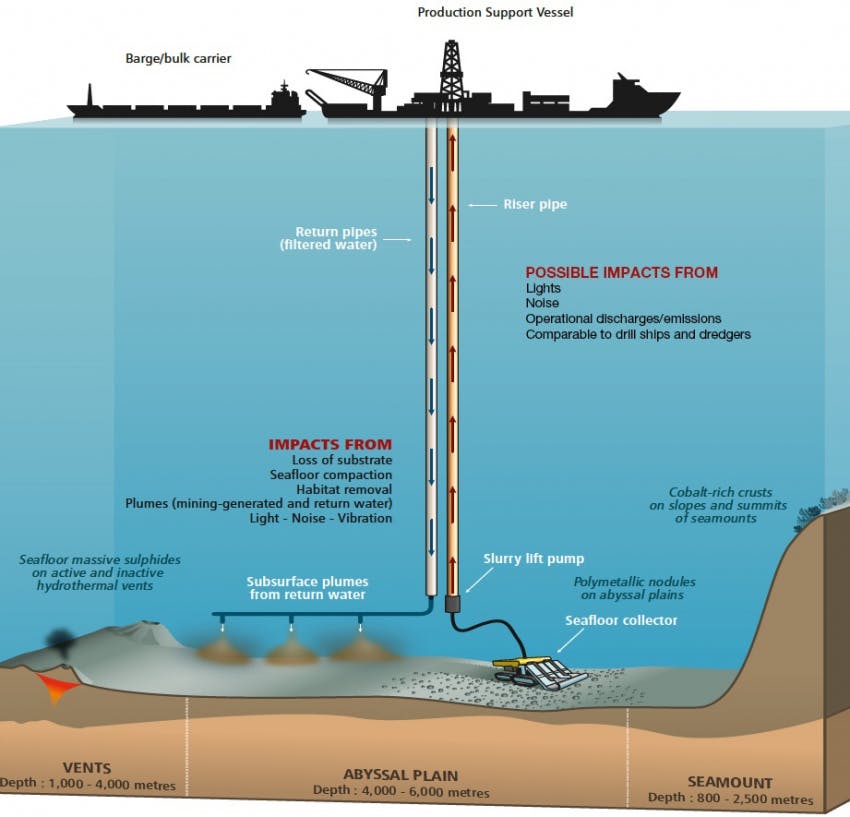

Deep-sea mining technology is still in development, but the general idea is that a submersible craft, about the size of a tractor, equipped with giant vacuum cleaners will draw sediment laced with precious metals from the seafloor, below 200 metres beneath the surface.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Collection vehicles creep across the bottom of the ocean in systematic rows, scraping through the top five inches of the ocean floor. The sediment is carried up several kilometres of pipes back to the operations’ mother ships, where metallic objects the size of potatoes, knows as polymetallic nodules, will be extracted. Unwanted sediment is flushed back into the sea.

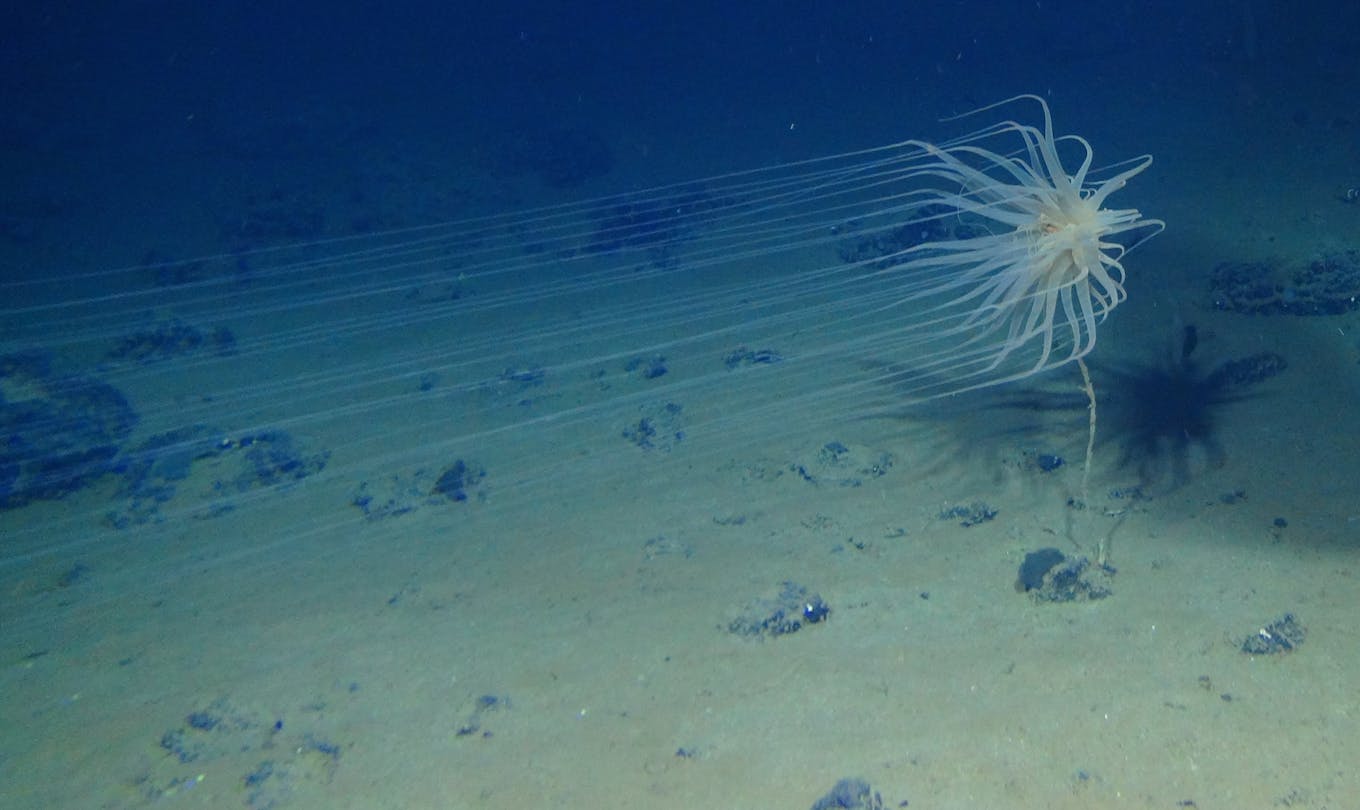

Relicanthus sp.—a new species from a new order of Cnidaria collected at 4,100 meters in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ) that lives on sponge stalks attached to nodules. Image courtesy of Craig Smith and Diva Amon, ABYSSLINE Project/NOAA.

How did it all start?

The first discovery of polymetallic nodules took place during the voyage of the Challenger warship tasked with exploring the world’s ocean and seafloor from 1872-1876. On 7th March 1873, a dredge hauled up on its deck “several peculiar black oval bodies which were composed of almost pure manganese oxide”.

In the century that followed, oceanographers continued to identify new minerals on the seafloor – copper, gold, silver, platinum, nickel and gemstones – with an economic interest in the deep-ocean polymetallic nodules developing as a result.

How is it regulated?

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is an independent organisation based in Kingston, Jamaica. Unlike the majority of UN bodies, it is classified as “autonomous” and falls under the direction of its own secretary general which convenes delegates from the 168 member states annually.

It is tasked with drafting technical and environmental standards that sit under the Mining Code. The Mining Code is the set of rules, regulations and procedures that will regulate all aspects of deep-sea mining – prospecting, exploration and exploitation – on the international seabed.

The exploitation regulations, including environmental issues, are not the only part of the framework that still needs to be developed: the ISA also needs to further develop proposals on the level of fees and royalties that contractors will have to pay, according to Aline Jaeckel, lecturer at the school of Global and Public Law, University New South Wales, Australia.

Members have struggled to agree on the regulatory framework that will govern this nascent industry and legal experts say that there is a lot of work to be done before the standards are adoptable.

What is the current state of play?

Deep-sea mining in international waters that do not belong to one nation, known as the Area Beyond Natural Jurisdiction (or The Area) – is currently at exploration stage until the exploitation regulations are established by the ISA.

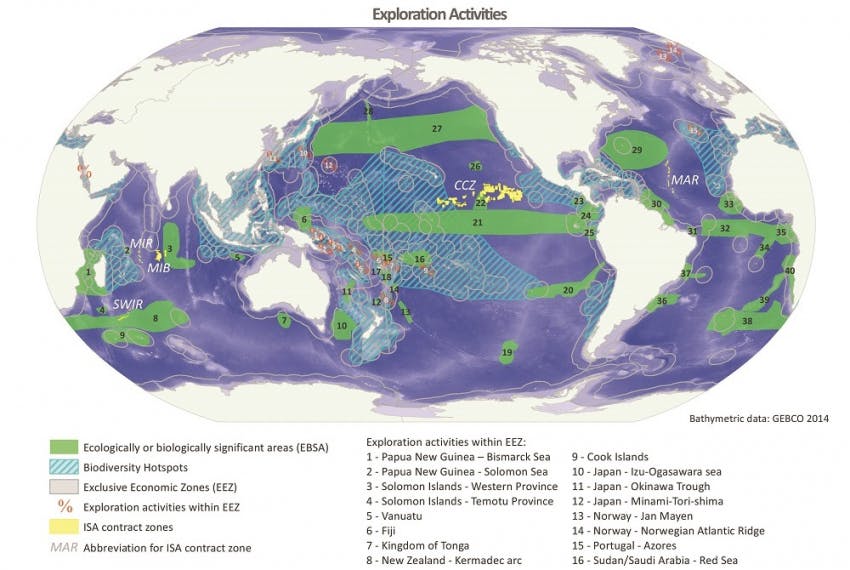

The ISA has granted about 30 exploratory permits around the world with the majority issued for the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ), a six million square kilometre region of the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii that is thought to host trillions of metal nodules containing manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, copper and traces of rare earth elements.

Once the Mining Code has been approved, more than a dozen companies that have raised vast sums of venture capital, will accelerate their explorations in the CCZ to industrial-scale extraction.

In June, the small Pacific island nation of Nauru, roughly 4,506 km northeast of Australia, notified the ISA of its intention to start deep-sea mining. Nauru’s President Lionel Aingimea asked the ISA to approve its plan within two years meaning that the agency will have to consider any application for a deep-sea mining license under the regulations that are in play at the time.

Deep-sea mining exploration activities [click to enlarge]. Image: International Union of Conservation of Nature

Some of the largest mineral corporations in the world have underwater mining programmes in territorial waters of certain countries.

De Beers, a diamond company, searches for the jewels around 120-140m below sea-level in the Atlantic ocean off the Namibian coast in Africa. Marine diamond recovery now produces more in annual volumes than the country’s land-based diamond mining operations, according to the company’s site.

Japan Oil, Gas and Metals National Corp (JOGMEC) has successfully deployed excavators to extract ore rich in zinc, gold, copper and lead from depths of 1,600 metres in waters close to Okinawa within the Exclusive Economic Zone of Japan.

But this frontier in ocean industrialisation is fraught with technical, environmental and financial issues.

A project to mine sulphides from hydrothermal vents in Papua New Guinea’s waters by Canadian company Nautilus Minerals Inc, was beset with repeated setbacks and spiralling costs that halted progress and led the company to file for insolvency months before operations were supposed to begin. The subsequent Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea described the arrangement as “a deal that should not have happened.”

What is driving demand for these metals?

In a report published earlier this year, the International Energy Agency found that acheiving net-zero emissions by 2050 would require six times more of certain minerals by 2040 than are being mined today.

The metals found in polymetallic nodules are critical for clean energy technologies such as wind turbines, solar panels, electric vehicle batteries and other energy storage devices.

The World Bank estimates that more than three billion tons of these metals will be needed to deploy the wind, solar and energy storage technologies required to keep global warming below 2°C.

Electric vehicles use at least four times the amount of metals found in petrol and diesel cars. A single electric vehicle with a 75 KWh battery needs 56 kg of nickel, 12 kg of manganese, 7 kg of cobalt, and 85 kg of copper for electric wiring.

What are the possible impacts?

A scientific analysis published in 2018, indicates that biodiversity loss from deep sea mining will be unavoidable. The authors also point out that the ecological consequences to deep sea biodiversity are unknown and will have inter-generational consequences.

As the deep sea remains understudied and poorly understood, there are many gaps in our understanding of its biodiversity and ecosystems. This makes it difficult to thoroughly assess the potential impacts of deep-sea mining and to put in place adequate safeguards to protect the marine environment. Image: International Union for Conservation of Nature

The scraping of the ocean floor by machines can alter or destroy deep-sea habitats, leading to the loss of species and fragmentation or loss of ecosystem structure and function.

Many species living in the deep sea are endemic – meaning they do not occur anywhere else on the planet – and physical disturbances in just one mining site can possibly wipe out an entire species, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

“Seventy to 90 per cent of species being discovered in the CCZ are new to science. That biodiversity is directly linked to many ecosystem functions and services that life on the planet relies on like climate regulation, links to fisheries, carbon sequestration, nutrients. And yet, we really don’t understand these species very well,” said Diva Amon, a deep ocean biologist and executive at the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative.

“We need to learn more about how CCZ species and the functions they provide impact us, how those communities may be impacted by mining, and what may be the best mitigation measures. And all of these are still very, very big question marks,” Amon told Eco-Business.

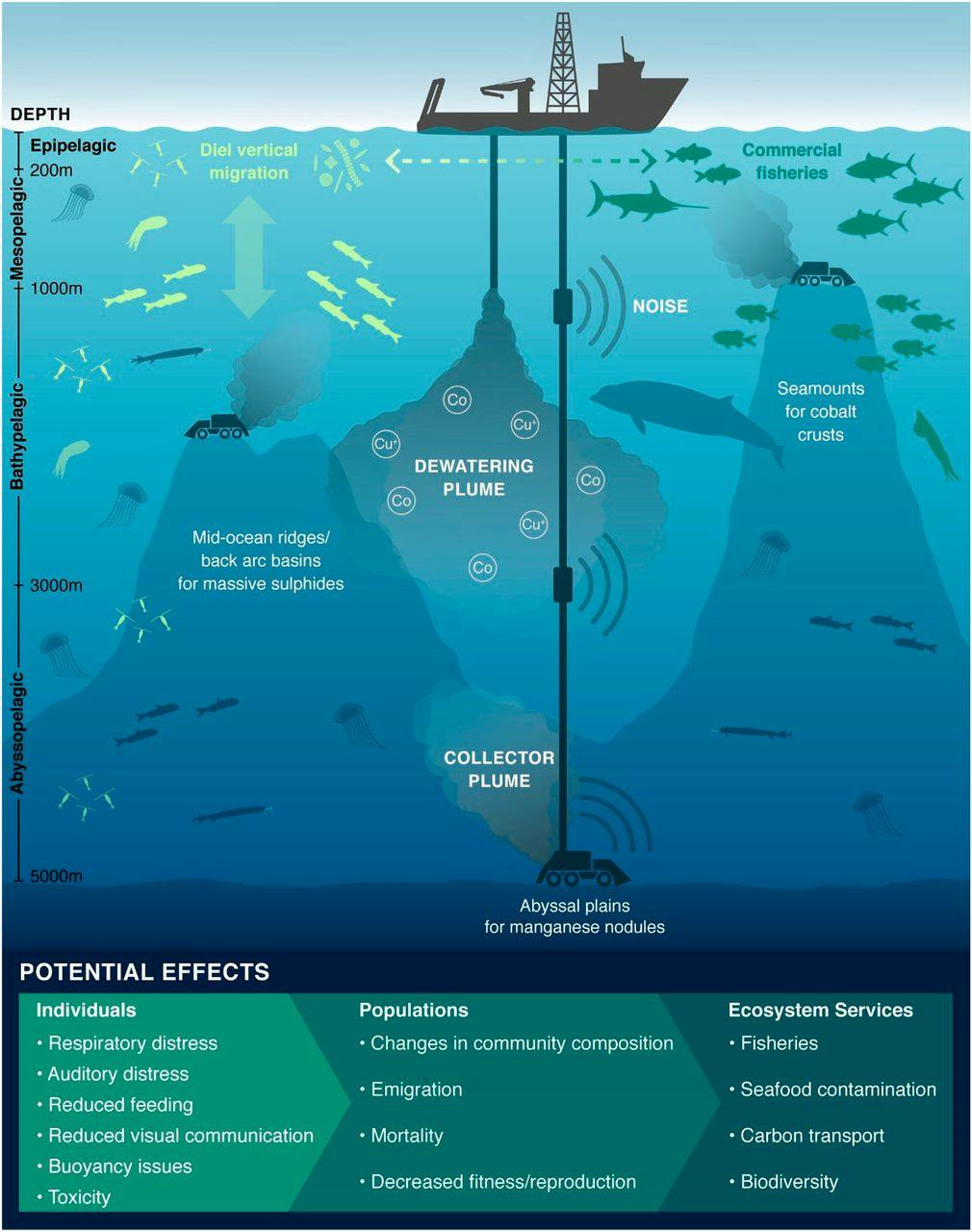

The extent of the sediment plumes and their impact on ocean-life is a key part of the environmental questions surrounding deep-sea mining. Some scientists fear that the slurry dumped back into the ocean could pose significant risks to midwater ecosystems.

The ISA believes that sediment released near the surface will travel no more than 100 km. However, a compilation of academic research compiled by Greenpeace concludes that “depending on where the plumes are released, this pollution could travel hundreds or even thousands of kilometres.”

There is also concern around how robust the ISA is and if it can adequately protect marine biodiversity.

“The ISA is designed to prioritise resource extraction, lacks expertise in protection, and its key Legal and Technical Commission meets behind closed doors; it is also unable to protect the seabed from cumulative threats beyond mining,” charged Greenpeace in a 2019 report.

Cross-party British MPs have also raised concerns over “a clear conflict of interest” that the ISA, as the body that is supposed to regulate the industry, “stands to benefit from revenues” during an Environmental Audit Committee in 2019.

Mining-generated sediment plumes and noise have a variety of possible effects on pelagic taxa. (Organisms and plume impacts are not to scale.) Image credit: Amanda Dillon (graphic artist). Source: https://www.pnas.org/content/117/30/17455

An environmental gamble

Scientists and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are concerned that the drive for deep-sea mining is happening too quickly and could unleash severe and irreversible environmental disasters to deep sea ecosystems.

Deep-sea mining advocates believe that the prized metals at the bottom of the sea are vital to creating a sustainable future on land. Deep-sea mining company, the Metals Company, also known as Deep Green, has claimed that there is enough metal in the sea-bed to supply the planet’s electric vehicles and clean energy needs while avoiding the problems associated with land mining such as biodiversity loss, toxic pollution and exploitive labour practices.

By reusing the metals already in circulation, and through urban mining, there’s no need to mine the deep-sea, according to the paper by the Institute of Sustainable Futures.

“Industry wants us to think mining the deep sea is necessary to meet demand for minerals that go into electric vehicle batteries and the electronic gadgets in our pockets. But it’s not so,” Jessica Battle, leader of World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)’s No Deep Seabed Mining Initiative said, following the publication of new research in February.

“We don’t have to trash the ocean to decarbonise. Instead, we should be directing our focus toward innovation and the search for less resource-intensive products and processes. We call on investors to look for innovative solutions and create a true circular economy that reduces the need to extract finite resources from the Earth,” Battle said.

Terrestrial mining experts believe that it is unlikely deep-sea mining will replace mining for the same metals on land but both will continue in tandem. Moreover, Nautilus’ failed venture in Papua New Guinea echoed many of the problems of land-based mines.

However, with the prospect and promise of significant economic and social benefits, decision-makers in the Pacific face a dilemma. Until commercial mining starts, there is little way to assess the social, cultural, economic and environmental impacts.

The lure of making money from the sea-bed’s riches may prove to outweigh any fears about the damage to delicate ecosystems.