At first glance, 38-year old Shahjahan Selim’s provision shop in Savar, Bangladesh, looks just like the hundreds of general stores dotting the subcontinent: colourful packets of snacks and household essentials line the shelves in the small room and dangle down over its windows.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But on closer observation, things are a little different here. Customers help themselves to goods, deposit their money into a small box, and take out change on their own.

The reason for this unusual set-up? Selim shattered his backbone when, over a two-week period, he rescued 37 people from one of the deadliest disasters in the history of the global garment industry: the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Savar on April 24, 2013.

“I did nothing exceptional, it was a small contribution,” says Selim, who slipped and fell during his rescue effort. After the tragedy, he set up his shop with help from the International Labour Organisation (ILO), but his mobility remains limited.

He was among the thousands of workers in the building when it collapsed shortly past half past eight in the morning. The disaster would ultimately claim more than 1,100 lives and injure about 2,500 others.

Selim Shahjahan in his shop in Savar, Bangladesh. Image: ILO

Outside Bangladesh, which relies on garment exports for US$19 billion in annual income, and a fifth of its Gross Domestic Product, Rana Plaza was so much more than a building collapse, say experts.

As Debbie Coulter, acting head of practice, evidence and learning at workers rights advocacy alliance Ethical Trading Initiative (ETI) puts it: “The events in Savar five years ago were a defining moment in terms of looking differently at how workers were treated in global supply chains.”

“It raised myriad issues that people have often taken for granted, such as social audits, worker representation, health and safety, and gender disempowerment,” she adds.

As the horrifying images from Savar made their way around the world, consumers responded with an almost-immediate backlash against fast fashion brands such as Primark, Mango, and Benetton, whose clothing labels were found in the rubble of Rana Plaza.

Meanwhile, civil society groups and unions scrambled to develop measures to ensure a similar tragedy never occurred again; and legal experts helped file a string of lawsuits seeking damages and compensation for affected workers.

But five years on, after the horrific images from Bangladesh have faded from memory and the fashion world has resumed its seasonal churn, how much has really changed when it comes to the well-being of the workers who make the cheap and trendy clothes worn daily by millions of people across the world?

It’s definitely safer…for some

One of the most noteworthy initiatives to emerge was the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, or the Bangladesh Accord. A legally binding agreement, the Accord has been signed by global trade unions IndustriALL and UNI Global; 190 companies including Primark, Benetton and Mango; two Bangladeshi trade unions; and a host of advocacy groups.

Key features of the Accord include the monitoring of some 1,600 factories of signatory companies by independent inspectors, who check for fire, electrical and building structure hazards; a requirement for companies to publicly disclose their factories, inspection reports, and plans to correct safety failures; and democratically elected health and safety committees in all factories covered by the Accord.

The Accord also empowers workers through measures such as a complaints mechanism, protecting their right to refuse unsafe work, and their freedom to organise and join unions.

Christy Hoffman, deputy general secretary, UNI Global Union—which helped broker the Accord—tells Eco-Business that when it comes to safety, the facts speak for themselves. “The industry in Bangladesh is far safer today than it was 10 years ago.”

“We identified 130,000 hazards across the factories, and 97,000 have been repaired,” says Hoffman. She acknowledges that many hazards remain unresolved, but this does not detract from the “major accomplishment” of the progress that has already been made.

The existing Bangladesh Accord expires in May this year, and a new 2018 Accord is currently in the works. But only 144 brands have signed onto the new one.

Parallel to the Accord, a smaller coalition of 29 brands including America’s Walmart, JC Penney and Nordstrom; and Australia’s The Just Group, have formed the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which focuses on safety and worker rights issues in the country.

But while things have improved significantly within the factories of signatory companies, ETI’s Coulter points out that smaller factories which make goods for domestic or non-Western markets are flying under the radar.

“It is difficult to drive change where big brands are not customers, because they have no leverage,” she tells Eco-Business. “But we are hoping that the transformation in large factories will have a trickle-down effect and set the tone for the rest of the industry.”

The collapsed Rana Plaza building. Image: rijans, CC BY-SA 2.0

In many of these factories, however, the local community is taking things into their own hands to keep workers healthy and safe. One such grassroots initiative is APON Wellbeing, which sets up shops inside garment factories and sells daily goods to workers at a discounted price.

Workers collect points when they spend in these shops, and can cash the points in for a year-long health insurance programme valued at US$210.

Helmed by founder Saif Rashid, APON Wellbeing currently operates three shop and offers coverage to 7,000 workers.

There is no upfront cost to factory owners beyond clearing a space for the shop, but factory owners he has approached have been reluctant to open their facilities to a third-party, Saif said.

But though uptake has been slow, Saif remains optimistic. “I believe there has been a huge increase in work addressing safety and infrastructure issues for garment workers, and more awareness and sensitivity of factory owners about worker issues,” he tells Eco-Business.

Initiatives such as APON Wellbeing may be making a difference at a small scale. But to stop safety and labour violations from going unchecked in smaller factories, government oversight is key, says Coulter.

“Many countries have commendable labour laws that would forbid the mistreatment of workers; but often, they are not enforced or respected,” she notes.

Indeed, exploitation of garment workers is not a problem confined to Bangladesh. Factories in China, Myanmar, Cambodia, Turkey, and even the United Kingdom have reported similar abuses.

In UNI Global Union’s Hoffman view, these global problems are the result of a governance gap, and governments must be the ones to fix it.

“We won’t really have an ethical industry until there is a level playing field across multiple countries, and Bangladesh doesn’t risk losing business to cheaper alternatives if they raise their costs too high,” she says.

Shabana, a former textile worker who survived the Rana Plaza collapse visits the site of the former clothing factory with four-year-old daughter Lamiya. Image: GMB Akash/Panos/OxfamAUS

Worker welfare remains poor

While there has been progress on safety issues, things are much more ambiguous when it comes to the question of overall worker welfare.

As Helen Szoke, chief executive of charity Oxfam Australia puts it: “[The Bangladesh Accord] leaves out a host of other issues [such as] poor wages, long working hours, physical and bodily exhaustion, intense work rhythms, harassment, child labour and forced labour.

In an industry where workers earn as little as 39 cents an hour, a key issue is a living wage. That is, pay for food, housing, healthcare, utilities, clothing, transport, education, and have some money left for emergencies.

While some niche brands ensure workers are paid a living wage, a report by Deloitte Access Economics found that for clothes sold in Australia, only 2 per cent of the retail price of a garment made in Bangladesh goes to workers. Paying workers a living wage would increase salaries by 76 per cent, and raise garment prices by just 1 per cent, Deloitte finds.

Indeed, a living wage is one of the key demands of the What She Makes campaign, Oxfam Australia’s latest in a string of labour rights advocacy efforts calling on brands to disclose the names and locations of supplier factories and uphold the basic rights of workers.

Across Asia, young women working in garment factories are regularly underpaid and forced to work excessive hours of overtime, and are still unable to afford suitable accomodation, feed their families or meet their basic health needs, says Szoke.

And brands can easily afford to pay workers more, says Oxfam Australia, pointing to the huge growth in brand revenue in recent years, and the multimillion dollar salaries of their chief executives.

Oxfam Australia wants companies to publicly commit to protecting the basic human rights of workers and pay them a living wage—and back up these commitments with a detailed strategy and timeline—but Szoke says that what’s needed to truly get to the heart of the problem is a Modern Slavery Act.

This is legislation which would legally require businesses to report on and address any instances of rights violation in their supply chain, and penalise those who do not.

But with such legislation still a subject of debate in many countries, and not even under consideration in other important markets, the reality today remains that many mass-market brands which are signatories to the Bangladesh Accord are selling t-shirts for as little as $3.50 a piece.

While it may be tempting to immediately assume that this equation is being balanced on the backs of exploited workers, ETI’s Coulter says that the price of a garment is not always a direct reflection of workers’ wages.

For instance, brands such as Swedish giant H&M may sell cheap clothes in their stores, but invest heavily in sustainability and worker welfare, she says.

And conversely, “just because I pay $500 for a blouse, it doesn’t mean the worker hasn’t been exploited,” she says, adding that this is why transparency about working conditions is crucial. “It’s not as simple as that.”

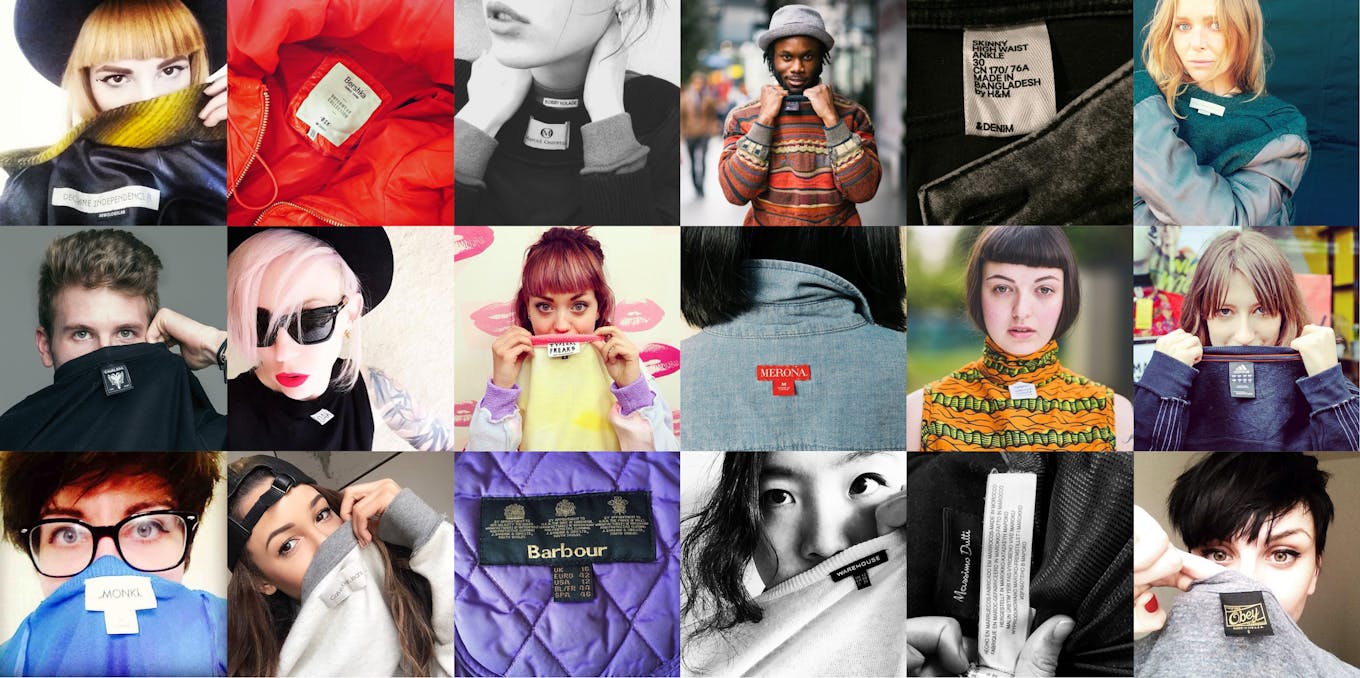

Once a year, conscious consumers take to social media to demand to know #WhoMadeMyClothes. Image: Fashion Revolution

How are major fast fashion brands doing?

1. Most of the brands involved in the Rana Plaza disaster have committed to safety

According to the Clean Clothes Campaign, brands that were sourcing from the factories in the Rana Plaza building include Benetton (Italy), Bon Marche (UK), Cato Fashions (USA), The Children’s Place (US), El Corte Ingles (Spain), Joe Fresh (Loblaws, Canada), Kik (Germany), Mango (Spain), Matalan (UK), Primark (UK/Ireland) and Texman (Denmark).

All of these companies are listed as signatories to either the Bangladesh Accord or the Alliance, except Cato Fashions.

2. But not all major fast fashion brands have done so.

While more than 200 brands have committed to safe factories, many other prominent names such as American brand Forever 21, Australian department store Myer, and Australian retailer Country Road have not signed the old or new Bangladesh Accord.

3. Progress on a living wage is slow

As Oxfam’s analysis shows, most brands fare poorly when it comes to paying workers fairly. Only H&M and Spanish brand Zara have any sort of a roadmap towards paying a living wage and are implementing it.

However, according to Oxfam Australia, Inditex has no timeframe for its roadmap, and little information is available on its progress.

H&M, which in 2013 committed to paying all workers a living wage by 2018, shows that wages in its factories have grown in the last five years. But while H&M supplier factories paid workers US$95 per month in 2017, the Global Living Wage Coalition says that a decent salary in Dhaka is closer to between US$177 and US$214 a month.

Both H&M and Zara’s parent company Inditex are members of the Action Collaboration Transformation platform, an industry initiative committed to a living wage. Other members include Primark, ASOS, Esprit, New Look, and Topshop.

4. How ethical is your favourite fashion brand?

A growing number of resources are helping consumers assess the ethical credentials of their favourite brands, and to find better alternatives to irresponsible companies. Here are some useful starting points:

Good on You, an app that scores brands on ‘people, planet, and animal’ criteria.

Baptist World Aid’s Ethical Fashion Guide, which rates more than 400 brands on their labour rights management systems.

Oxfam’s Company Tracker, which assesses how brands popular in Australia fare on transparency, worker rights, and delivering a living wage.

The ACT Platform lists companies around the world which are facilitating the payment of living wages to workers.

Brands have been slow to act. Are consumers picking up the pace?

Every March 24, the hashtag #WhoMadeMyClothes lights up social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram, where a veritable flood of concerned consumers post photos of their clothing labels and demand to know where and how their garments were made.

The coordinated call for transparency is meant to demonstrate to fashion brands that shoppers want to know more than just how much that cute t-shirt costs. Were workers paid fair wages? Were they working in fire-safe factories? These are just a few of the questions that global campaign Fashion Revolution urges consumers to ask their favourite brands each year on the anniversary of the Rana Plaza tragedy.

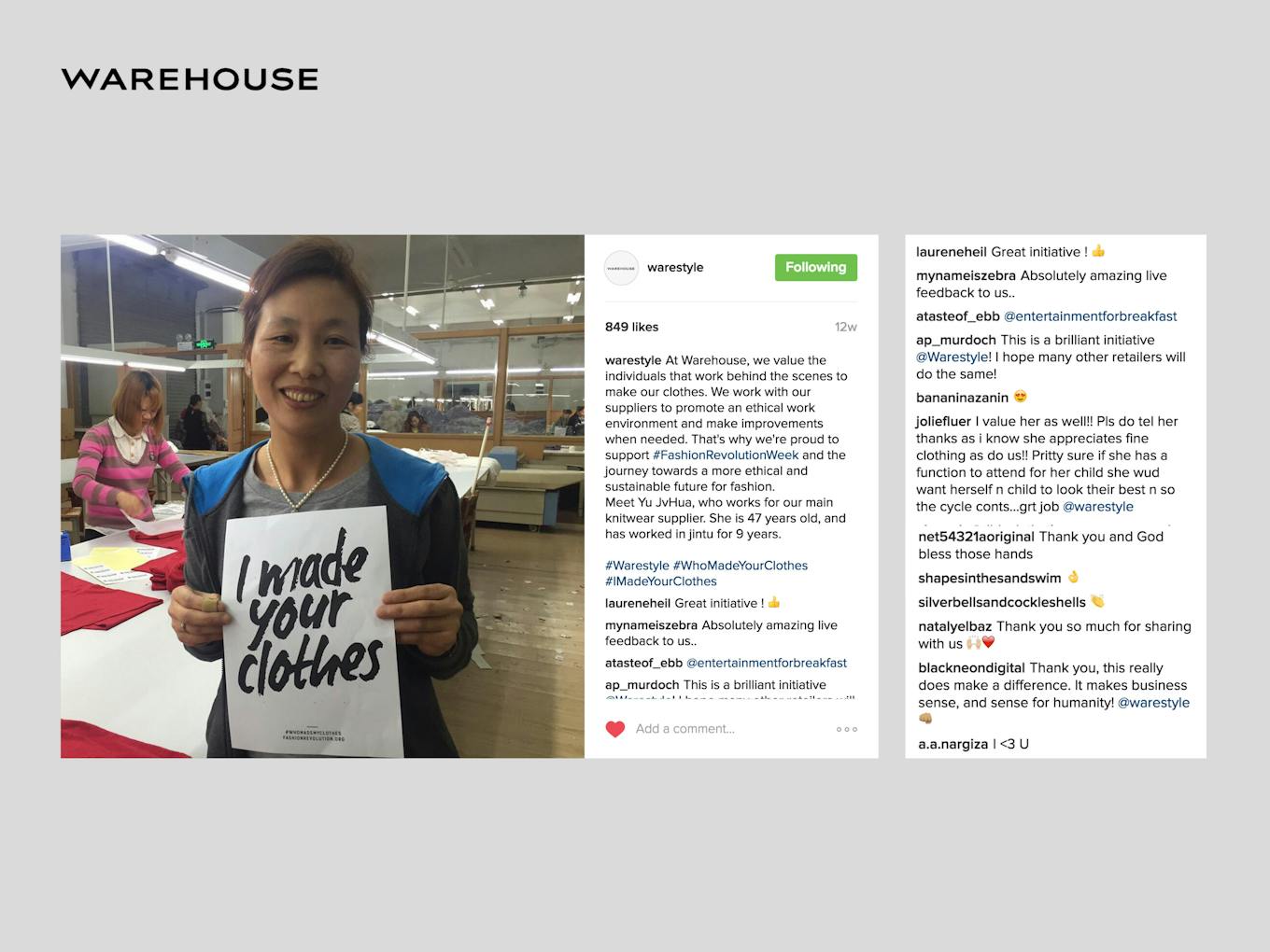

For brands with stories to tell, Fashion Revolution is an invaluable opportunity for them to prove their sustainability cred. A quick search on social media reveals photos of garment workers holding up signs saying “I made your clothes”, while brands including Marks & Spencer are replying to tweets and pointing curious consumers to their supplier lists.

As one of the biggest movements drawing attention to the unjust working conditions of garment workers and the negative impacts of the fashion industry, Fashion Revolution also features a week’s worth of workshops, film screenings and discussions on the topic.

But do consumers care about ethical fashion during the other 51 weeks of the year?

There has always been a certain level of awareness around the need for ethical consumption and production, but the scale of the Rana Plaza tragedy brought these issues to the forefront of public consciousness, says Gordon Renouf, co-founder and chief executive officer of Good On You. The mobile app tells consumers how ethical apparel brands are, to make it easier for them to make better purchasing decisions.

“But I think it’s a general sense that we’re making more stuff in other parts of the world, and some countries have weaker labour and environmental laws,” he explains. As societies become richer and more materially comfortable, people begin to place more emphasis on these value-based issues too, he adds.

A Nielsen study from 2015 found that three-quarters of Millennial consumers—that is, people born between 1982 and 2004—were willing to pay more for sustainably produced goods. “It may not be true that they’d pay more, but it’s true that they’re aware that there are issues,” Renouf notes.

Fashion retailers are increasingly introducing clothing lines that are more environmentally or socially friendly, including H&M’s Conscious collection, ASOS’s Eco Edit section for more sustainably produced garments, and Adidas’ tie-up with Parley for the Oceans. Renouf points out: “If these brands didn’t think there’d be a significant cohort of customers who would respond favourably to these offerings, they wouldn’t be making such a point of doing them.”

But these offerings are, at the moment, a drop in the ocean when it comes to international demand for clothing. According to the Pulse of the Fashion Industry report, global apparel and footwear consumption is expected to rise from 62 million tons to 102 million in 2030—the equivalent of 500 billion t-shirts.

Consumers have also been trained to see cheap clothes as a given, and that’s part of the problem, says Renouf. “People say ethical clothes are expensive, but they’re not compared to what clothes cost 20 to 30 years ago. The price of clothing has, relative to things like basic household accessories and food, gone down quite a lot,” he elaborates.

“We just buy more of them.”

British fashion label Warehouse profiles a garment worker in its supply chain as part of Fashion Revolutions’ #WhoMadeMyClothes campaign. Image: Fashion Revolution

Buy better or buy less?

But while retailers start responding to consumer demand for ethical fashion, buying sustainably made products alone may not get to the heart of the issue, say experts.

Laura Francois, country head for Singapore, Fashion Revolution, said that the messaging behind sustainable shopping has to evolve. “In the last five years [since Rana Plaza], people have gone from not understanding the concerns around sustainable fashion, to understanding them and wanting to help, and their way is to buy more of the good stuff,” she tells Eco-Business.

But that in itself is a problem, because producing clothes still uses resources and responsible disposal methods such as recycling would nevertheless take up time and energy, Francois notes.

Instead of buying better, the messaging around sustainable fashion needs to be buy less, and know what you’re buying, says Francois. “Being curious about how a product was made can propel you into a moral conundrum, because you’ve discovered that it was created in a place where workers weren’t paid properly. Then you can make your own decision about whether to buy it or not.”

A clothes swapper in Singapore. Image: Swapaholic

Instead of buying 100 ethically made shirts, for instance, it would be better to purchase just one product and use it for a long time, she adds.

At the same time, there needs to be a change in the way that people interact with and relate to fashion.

“For any product, if the designer chooses to use unsustainable materials in its creation, it’s not our fault as consumers if we have to choose between lousy options,” says Francois.

By considering what motivates people to purchase clothing—perhaps the desire to be fashionable, or to avoid walking around naked—industry can begin to tailor different options to meet those needs without generating excessive consumption, she explains.

For instance, one solution she finds has worked well in Singapore is clothes swapping, where people donate their old clothes in exchange for other people’s pre-loved garments.

Another option is clothes rental services in the form of subscription boxes, where consumers pay an ongoing fee to have a number of items sent to them each month. Once the wearer gets tired and wants to change their wardrobe, they mail the old clothes back and order new ones to keep boredom at bay.

Sustainability in vogue

But ultimately, brands must take responsibility for designing better products and ensuring transparent, ethical supply chains as some have done, say experts.

Much blame has been laid at the feet of fast fashion business models, but that doesn’t mean that brands aren’t making an effort, says Renouf. “There are the H&Ms of the world that are fast fashion, but are developing new solutions to problems, recycling polyester being a particularly interesting one.”

“In our hearts we may prefer that consumers shop from certain brands rather than major fast fashion labels, there are other fast fashion and non-fast fashion companies that are worse on labour rights or environmental sustainability, and we call that out,” Renouf says of his app.

He says it’s also critical to be fair to companies at different stages of creating sustainable supply chains in order to encourage change within the industry. “One of the reasons brands don’t take that first step [to be more sustainable] is that critics say they’re just being tokenistic.”

“My response to that is to address it by developing a long-term action plan and demonstrate that you’re serious about it,” he adds.

Francois calls the lack of sustainable fashion choices on the market a design problem. “If you had two amazing looking products, one that didn’t harm the planet and one that did, I have a feeling nobody would choose the second. We have shitty products designed in a shitty way, what other choice do consumers have?”

Ultimately, while consumers should put more thought into their purchasing decisions, the burden cannot be borne by customers alone, says UNI’s Hoffman.

Advocacy groups frequently ask people to pay more for better quality clothes and use them longer, and consumers can put pressure on reputation-conscious brands to change their practices.

But she adds: “I don’t really think that’s the solution. We need binding rules so that companies know that there are rules that apply to them and everyone else, and they can’t make a profit by cheating workers out of a decent life.”