Singapore could clear an area of forest larger than the city-state’s nature reserves and parks combined to fulfil its urban development ambitions, according to new research that references its latest statutory land use plan.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

According to analysis in a paper published in a peer-reviewed science journal earlier this year by Switzerland-based MDPI, Singapore is set to convert an estimated 7,331 hectares of secondary forest – that is, previously cleared forest that has regenerated – mainly to make way for public housing over the next 10 to 15 years, according to the tropical country’s urban development plan mapped out in the study. This is about 1.2 times larger than an entire area of all parks and nature reserves in Singapore, said the study.

The researcher, Yitong Wu, is a former student from National University of Singapore (NUS) who now works for the Department of Municipal Landscape Management at Huizhou Urban and Rural Management and Comprehensive Law Enforcement Bureau in China.

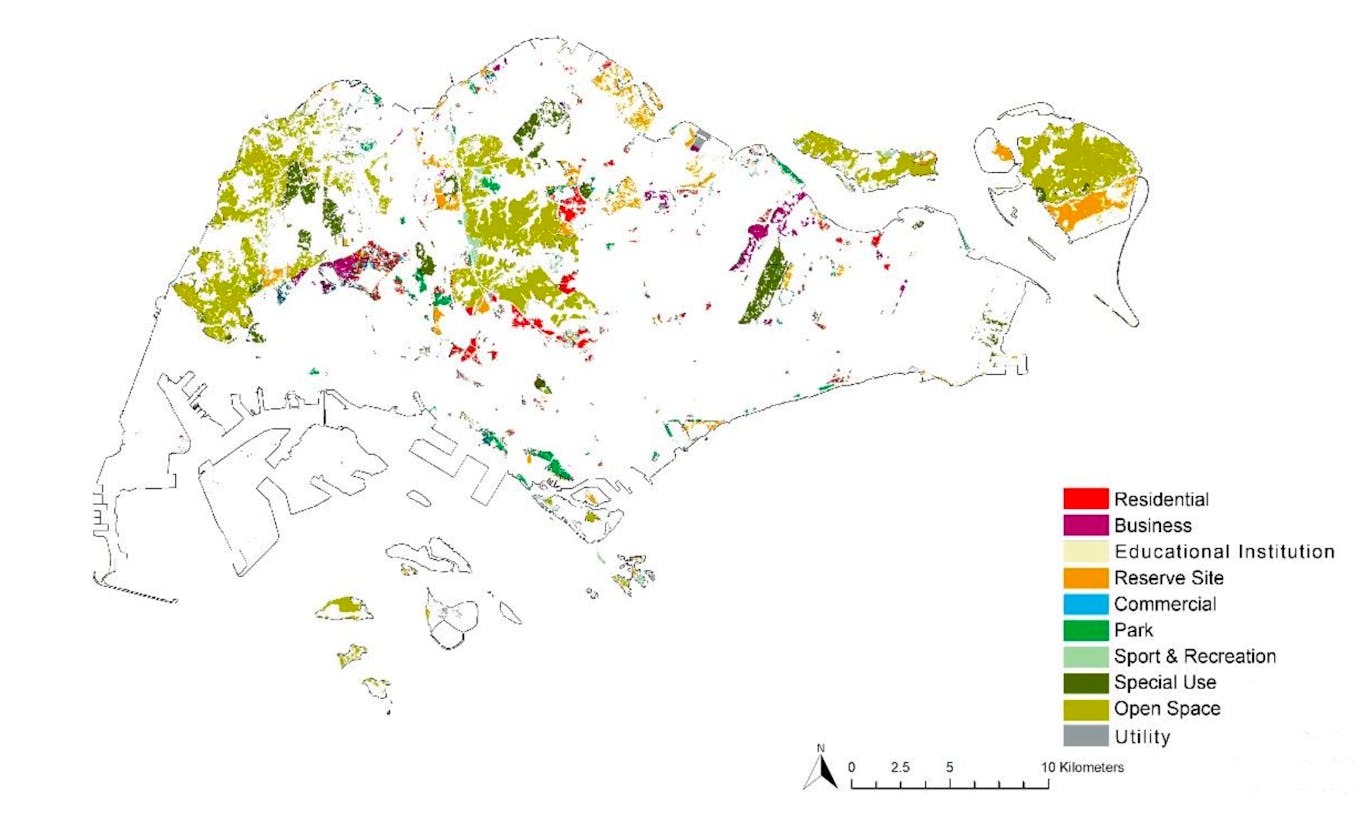

In her research, Wu took Singapore’s current land area covered by unprotected secondary forest and overlaid it with the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s (URA) 2019 masterplan, and found that more than half (54.3 per cent) of the island’s remaining secondary forests could be lost to development.

“

We are smaller than other metropolitan cities like London, New York or Hong Kong, and yet, need to find space to meet all the needs of both a city and a country.

Urban Redevelopment Authority and National Parks Board, in a joint response to the study

Of the planned forest clearance, 7.34 per cent will be converted for residential buildings, 4.79 per cent for parks, 3.37 per cent for commercial and business development, 1.45 per cent for sports and recreation and less then one per cent (0.98 per cent) for educational institutions, the study estimates.

What Singapore’s secondary forests will be used for in the future, according to the URA 2019 Master Plan mapped out by researcher Yitong Wu. Source: Study towards Integrating Secondary Forests into Future Land Use Development in Singapore for Biodiversity Objectives

Singapore is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, but still has a relatively high proportion of green spaces – around 20 per cent of the island – relative to its size, at 72,860 hectares. Secondary forests account for about one-fifth of the country’s green spaces. Only 0.16 per cent of its land area is covered by primary forests.

The small island nation has an ambition to become a “city in nature” by 2030, a continuation of a national greening plan that was started in the 1960s by late prime minister Lee Kuan Yew. The latest version of that plan includes the addition of new nature parks, better connected green spaces, and planting one million trees by 2030 – a target the government said recently it is ahead of schedule on.

“

Defence, transport and housing have taken priority in Singapore historically. Shouldn’t climate change now be the top priority? The developments that are replacing forests, such as housing and outdoor sports venues, could become stranded assets as Singapore warms.

Dr Lahiru Wijedasa, botanist and conservationist

However, the masterplan detailed in Wu’s study could effectively mean 10 per cent of the country’s entire land area would be converted from secondary forests to some sort of man-made utility. Any patch of forest can be converted at any time, since all land is state-owned.

In a joint response to the study from the URA and National Parks Board (NParks), a spokesperson said that the author had assumed that vegetated areas zoned for development under the master plan would be completely cleared of forest. “This is not the case as some vegetated sites within the land parcels could be conserved.”

The government cited examples of this, such as the Bidadari housing estate, where a one-hectare hillock was preserved as a habitat for migratory birds, and the reduction and movement of work sites in sensitive areas where a new subway line, the Cross Island Line, is being built.

“Prior to approval, all development proposals are subject to a robust planning evaluation process that considers the developments’ impact on the environment,” the spokesperson said.

The statement added that the study did not distinguish between different vegetation types, and noted that some secondary forests are on reclaimed land, such as those near Changi Airport, or were cleared previously, left vacant, and are largely dominated by non-native species.

Most of the forests dominated by native tree species in Singapore have been conserved as nature reserves and parks, it said. To date, NParks has “conserved more than 450 hectares of forested areas surrounding Singapore’s nature reserves” as nature parks.

‘Alarming’ consequences for biodiversity

Dr Ho Hua Chew, the vice-chairman of the conservation committee at non-governmental organisation Nature Society (Singapore), said the scale of future forest loss highlighted in the study could have “alarming” consequences for biodiversity in the city-state – which is already being impacted by ongoing development.

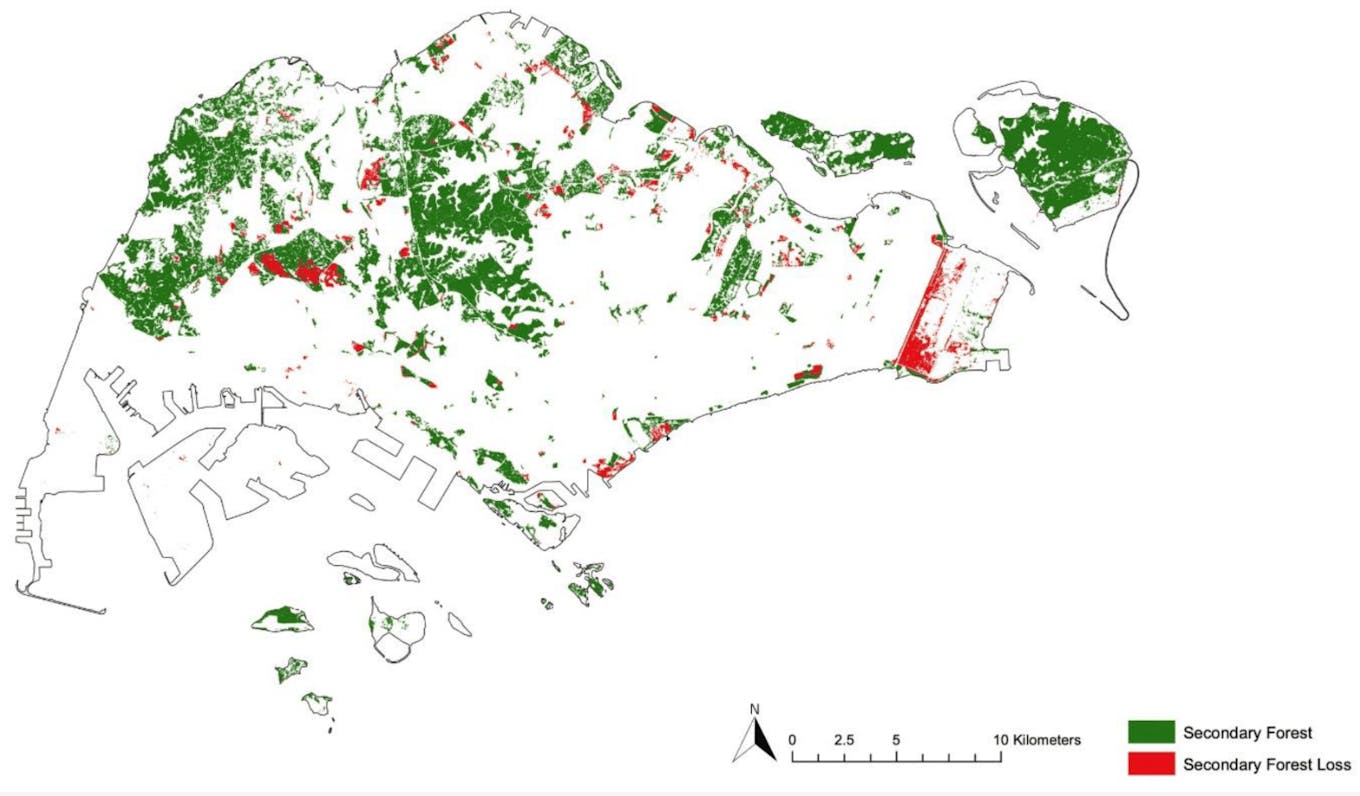

Wu’s study estimated that 1,782 ha of secondary forest cover in Singapore has been lost to urbanisation over the past decade, and the remaining forests are becoming more fragmented.

More than 80 per cent of Singapore’s secondary forest patches are smaller than one hectare, according to her study. However, most of the forest patches have high plant density and high biodiversity value in terms of ecological connection, the study noted.

Changes in secondary forests in Singapore from 2011 to 2021, based on NDVI analysis and satellite imagery observation. Source: Study towards Integrating Secondary Forests into Future Land Use Development in Singapore for Biodiversity Objectives

Many of Singapore’s secondary forests, having regrown over plantations and abandoned kampungs (rural villages) as people traded rural living for high-rised flats over the past century or so, are important habitats for species such as long-tailed macaques, colugos, mouse deer and the critically endangered Sunda pangolin, which use forest patches to move around the tropical island, hailed the world’s most biodiverse city in the BBC documentary Planet Earth II.

In 2021, Singapore recorded an unusually high number of pangolins killed on its roads. Last year was another bad year for pangolin roadkills, with poor connectivity between forest patches cited among the reasons for high morbidity. Ecologists such as Dr Andie Ang, a specialist in Raffles Banded langurs, of which only around 70 individuals remain on the island, have expressed concern that the forest patches could be too small to support genetically healthy populations, who may start inbreeding.

Two of the critically-endangered primates died on Singapore’s roads last year, trying to cross from one forest patch to another, possibly to find mates, Ang has said.

The government said it has established new nature corridors, such as in Khatib in the north, and Clementi in the west, to serve as “ecological stepping stones” to connect key habitats, and has conserved more than 450 ha of forested areas surrounding Singapore’s nature reserves as nature parks.

It added that it has safeguarded 7,800 green spaces with plans to set aside another 1,000 ha of green spaces over the next 10 to 15 years.

The city’s secondary forests that are currently being cleared include Tengah forest, much of which is being cut down to create a 700-hectare “forest town”. Tengah is the first housing town to be developed since Punggol, in the northeast of the city, two decades ago.

A road being built to connect the new town with a major arterial highway could affect 13 ecologically-important plant species and reduce the habitat for rare fauna like the harlequin butterfly and blue-eared kingfisher, according to an environmental impact assessment (EIA) commissioned by Singapore’s Land Transport Authority.

Work has started to clear Dover forest, a 33-ha patch of secondary forest that was formerly a rubber plantation, orchard and kampungs, to create a high-rise residential area. Following pushback from nature groups and a citizen-led petition to conserve the forest, the project was re-designed so that only the eastern portion of the forest would be cut down. The forest contains 158 species of fauna and 118 species of flora, according to an EIA completed in 2017.

One citizen in social media linked the felling of Dover forest to Singapore’s recent heatwave, while another said it was “depressing” to hear the cracking of falling trees as excavators cleared the area in view of residents from their high-rise apartment blocks.

The clearing of Dover forest on 17 June 2023. The secondary forest, which has regrown over abandoned plantations, orchards and rural villages after World War II, has been earmarked for residential development since 2003 as the Ulu Pandan estate site. Image: Donald Pang on Facebook. The photograph was taken by Sandy Boey and posted on Mustsharenews.com

Singapore’s forests and urban heating

The loss of secondary forests not only matters to the island’s rich biodiversity, but could have consequences for liveability in the tropical city-state, say experts. Singapore is already heating twice as fast as the global average, partly as a result of the urban heat island effect – that is, when cities replace natural land cover with concreted surfaces that absorb and retain heat. The urban heat island effect could increase energy costs – for instance, for air-conditioning – air pollution levels, and heat-related illness and mortality.

The loss of secondary forests could lead to further localised heating in urban areas, suggests Dr Lahiru Wijedasa, a botanist who works on conservation and climate projects around Southeast Asia. Singapore is 4°C hotter in built up areas than forested areas and a Singapore that is projected to get as hot as 35°C to 37°C by the end of the century – the commuter belt of Ang Mo Kio recorded a 40-year high of 37°C in May – could be an uncomfortable place to live, particularly for people who work outdoors or can’t afford artificial cooling, he said.

“Singapore is losing greenery in some areas, and conserving it or gaining it in others,” said Wijedasa, pointing to the development of new parks and hiking trails that have sprouted in recent years, such as Rifle Range, Windsor and Bukit Gombak parks. The big question about losing or conserving forests, he said, is the impact on local temperature, humidity, rainfall patterns – forest loss has been linked to a reduction in rainfall in the tropics – and ultimately human comfort.

“We don’t know the effects of losing or conserving forests in Singapore yet,” he said. There have been no formal studies on how land use change has or will affect the local climate in Singapore to date.

Wijedasa wonders how much of the 7,000-plus ha of unprotected forest will be lost and how much should be prioritised for conservation to mitigate climate impacts.

When the Bukit Timah Expressway, a highway that cuts through Singapore’s biggest nature reserve, was built in the 1980s, it was generally accepted that a natural area had to be sacrificed to meet the city’s transport needs. But more recently, the development agenda is being questioned as the value of natural areas in mitigating climate change has become clearer, Wijedasa said.

“The next five years have been predicted to be the warmest the planet has ever witnessed. Defence, transport and housing have taken priority in Singapore historically. Shouldn’t climate change now be the number one priority? The developments that are replacing forests, such as housing and outdoor sports venues, could become stranded assets as Singapore warms.”

In response to a question from Eco-Business on urban heating, the government agencies, in the joint statement, said that Singapore’s “One Million Trees’ tree-planting scheme included the planting of 170,000 trees in industrial estates, which are among the hotter areas in Singapore. “Through these efforts, we will mitigate the urban heat island effect while bringing Singaporeans closer to nature,” a spokesperson said.

Singapore is set to also launch an official heat stress advisory that will guide its people on how to plan their activities, and even the type of attire they can wear for outdoor activities, in hotter weather.

Integrating secondary forests into urban planning

The study calls on Singapore’s policymakers to consider integrating secondary forests into future developments rather than remove them, for instance by nestling residential areas alongside forests or retaining forests within parks, to preserve biodiversity and mitigate urban heating.

Local conservation group Cicada Tree Eco Place supports the idea of building with rather than on top of forests, which it says is a more cost-effective strategy than building artificial nature measures, like estate parks and densely planted urban trees, which do not provide the same ecological or climate mitigation benefits.

The group pointed to the Windsor and Rifle Range Nature Parks as good examples of forest patches that sustain biodiversity while remaining accessible to the public in Singapore.

Muhammad Nasry, executive director of advocacy group Singapore Youth Voices for Biodiversity and also part of environmental group LepakinSG, disagrees with some of the report’s recommendations, including how residential areas should be integrated with forests.

“You can partially develop a forest and still retain a forest corridor for connectivity purposes. However human activity should, as much as possible, be excluded from this corridor so as to maintain its [ecological] value.”

“Any small patch of forest with a significant human presence will generally not be able to serve its ecological function well,” he said.

Also, integrating forests with residential areas could be “a recipe for disaster if the potential for future human-wildlife conflicts is not sufficiently mitigated,” he said. Singapore generally has a low tolerance for wildlife, which is often culled in response to complaints from residents. Some 50 wild pigs have been culled in Zhenghau Nature Park since 2019.

Dr Ho of Nature Society (Singapore) said that the conservation measures the study suggests are reasonable, but the study does not question whether some developments, such as Tengah, were worth executing at all, given their ecological cost.

“Why have such a large township there [in Tengah] at all, given that the forest there is rich in biodiversity? What about questioning the extent of the development in the first place?” he said.

The key question, he added, is whether some development plans can be curtailed to allow for more natural habitat in a country that is well below the Convention on Biological Diversity’s [CBD] benchmark for countries to reserve 30 per cent of their land and marine areas for conservation.

“At this stage we fall far short of this [CBD] benchmark, and things will get worse if the development plans referred to in the study are carried out,” he said.

The government spokesperson, however, said that its land use plans “are not static,” and would be regularly reviewed with the community “as consensus on the balance between environmental conservation and development evolves.”

“The government is committed to retaining land for as long as it is not needed for development,” the spokesperson said.