The colors of northwestern Australia are profound. In the build-up to the wet season, the deep shades of bloodwood trees (Corymbia spp.) and red-tailed black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus banksii) take on an extra vibrancy. This place is called Yulleroo by the Yawuru people, whose ancestral lands lie in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, Australia’s largest state.

Micklo Corpus, a Yawuru man and Traditional Owner of this country, walks through the bush until the tussocks of spinifex grass (Triodia spp.) give way to a wire gate. Behind it lies a hydrofracturing well belonging to the Australian mining company Buru Energy. The process of hydrofracturing, or fracking, involves injecting a high-pressure fluid of sand, water and chemicals into a drilled well to free natural gas from rocks deep underground.

Having lived on these lands for generations, the Yawuru people are recognised as Traditional Owners under Australian law. As such, the people have certain rights to their land and waters, as well as a responsibility to protect, promote and sustain them.

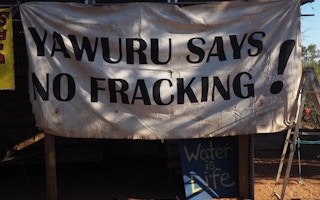

“As custodians, we were put on Earth in this form to look after the land,” Corpus says. “Our people have cared for [our] country for thousands of years, and fracking is a risk to our environment, to our water.” He shakes his head. “The issue is, they won’t listen to our concerns.”

The Kimberley, roughly the same size as California, encompasses the northern reaches of Western Australia. The area is internationally renowned for its intact natural landscapes and for being home to the oldest continuous culture in the world.

The North Kimberley is recognised as the last mainland refuge for many mammal species, including marsupials such as the golden bandicoot (Isoodon auratus). Its coastlines are among the world’s most pristine, comparable to those of Antarctica, and it houses the largest, most unspoiled savanna on Earth.

It is also extremely rich in mineral and hydrocarbon deposits. Therefore, it is no surprise that the most contentious environmental debate currently facing the Kimberley involves what lies beneath its red soil. The region sits on top of the Canning Basin, which holds Australia’s largest shale gas reserve. As the international energy market turns away from coal and oil to cleaner-burning alternatives, developers like Buru Energy have been busy acquiring mining licenses that span the Kimberley.

With questions surrounding the impact of fracking on the environment, a moratorium on the technique has been in place across Western Australia since September 2017. However, this may change with an independent scientific inquiry due for publication by the end of the year. If the moratorium is lifted, developers will have the potential to drop 40,000 wells across the Kimberley. This would represent almost one fracking well for every person in the sparsely populated region.

The precedent for mining is certainly there: Australia has tapped into its mineral reserves so comprehensively in recent years that it is currently forecast to become the world’s biggest producer of liquefied natural gas in 2019. Ironically, the country is also home to some of the world’s most expensive domestic energy prices, as much of the local production is shipped to a burgeoning Asian market hungry for energy.

This international demand and its effect on domestic prices has convinced some of Australia’s state governments to embrace fracking. Earlier this year, Australia’s third-largest federal division by area, the Northern Territory, approved fracking following the publication of its own independent inquiry.

However, the decision was met with controversy due to some of the inquiry’s findings. The inquiry highlighted that “high conservation value” areas in the Northern Territory might be compromised and expressed concern that “the broader Aboriginal community has not been adequately informed about [the] shale gas industry and its potential impact on Aboriginal communities.”

In the wake of the Northern Territory decision, the ruling Labor Party in Western Australia has remained largely silent about the potential effects of fracking on both the environment and the community.

However, one politician who has expressed her opposition to lifting the fracking moratorium is the state member for the Kimberley, Josie Farrer. Farrer, a member of the Labor Party and a Kija woman from the Halls Creek region, has called for a permanent state-wide fracking ban.

In a social media statement earlier this year, Farrer broke ranks with her own party in outlining her concerns. “It is my cultural responsibility to protect the native lands of my people,” she said. “I urge all my Kimberley mob and the people of Western Australia to join me in keeping the pressure on the State Government until we see a full ban on fracking in the Kimberley and all of Western Australia.”

Farrer’s comments reflect the limitations of Aboriginal land rights currently enshrined in Australian law. Internationally touted as a seminal development in First Nations affairs, the Native Title Act (NTA) of 1993 confirmed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples would have rights and interests to land and waters based on traditional law and custom.

However, the NTA only recognises ancestral connection; it does not grant Traditional Owners legal ownership of the land or the ability to veto development. Traditional Owners are only granted the right to negotiate over their interests.

The Yawuru people’s situation at Yulleroo illustrates these constraints. Buru Energy drilled two exploratory wells, Yulleroo 3 in 2012 and Yulleroo 4 in 2013, successfully discovering gas deposits. In 2014, the Australian Department of Mines and Petroleum approved Buru Energy’s gas exploration program, giving the company the green light to begin fracking shale gas reserves located between 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) and 5 kilometers (3 miles) underground.

The same year, members of the Yawuru people’s Native Title decision making body voted overwhelmingly against Buru’s plan to frack on their Native Title land. They expressed concerns that there was a lack of information about the safety of fracking following a reported gas leak at Yulleroo in 2013.

This appehension was compounded by reports of a second gas leak in 2015, and concerns of water contamination were raised after Yulleroo 3’s fracking pads were submerged by monsoonal rains during the most recent wet season, spanning October 2017 to March 2018. Buru Energy had previously deemed such a situation nearly impossible. Although the Yulleroo wells were inactive at the time due to the state-wide moratorium, the company could resume production there if the moratorium is lifted.

Without the right to veto development, the Yawuru Traditional Owners’ only remaining recourse has been to request that Buru Energy agree to meet certain conditions. However, under Australian law, companies are not required to do so.

Buru Energy did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. However, the company has previously asserted that it respects the Yawuru Traditional Owners and “will address their concerns [around fracking].”

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com. Read the full story.