When Italian architect Carlo de Sanctis went to a friend’s wedding on the outskirts of Rome two years ago, he did not expect to find himself discussing food waste.

As the party was winding down, de Sanctis and his friends ended up wondering what the waiter next to them would do with the uneaten food he had started to collect.

“We asked him what they were going to do with all this leftover food and he showed us the garbage. We couldn’t believe all this excellent food would simply get wasted,” he said, still in disbelief.

De Sanctis felt compelled to act. With his friends, two lawyers and a web designer, he set up Equoevento, a Rome-based non-profit that collects uneaten food from events and delivers it to charities for distribution to the hungry.

“On one side you have so much leftover food, and on the other side there is no food at all. We saw every day that there were so many people that didn’t have enough food,” de Sanctis told the Thomson Reuters Foundation, explaining that “equo” means “equal” in Italian.

Between 30 per cent and 40 per cent of food produced around the world is never eaten because it is spoiled after harvest and during transportation, or thrown away by shops and consumers.

Yet almost 800 million people worldwide go to bed hungry every night, according to U.N. figures.

The problem has become so serious that halving world food waste by 2030 was included as a target for global development goals adopted by world leaders in 2015.

From Italy to Germany and Brazil to Kenya, a growing number of enterprises are rescuing food that would otherwise go into landfills to feed those in need - a trend some experts say may be the answer to the mountains of food waste created daily.

Equoevento has so far distributed 200,000 meals from food collected from some 400 events. Entirely run by volunteers, the organisation may soon need to seek office space as it expands, de Sanctis said.

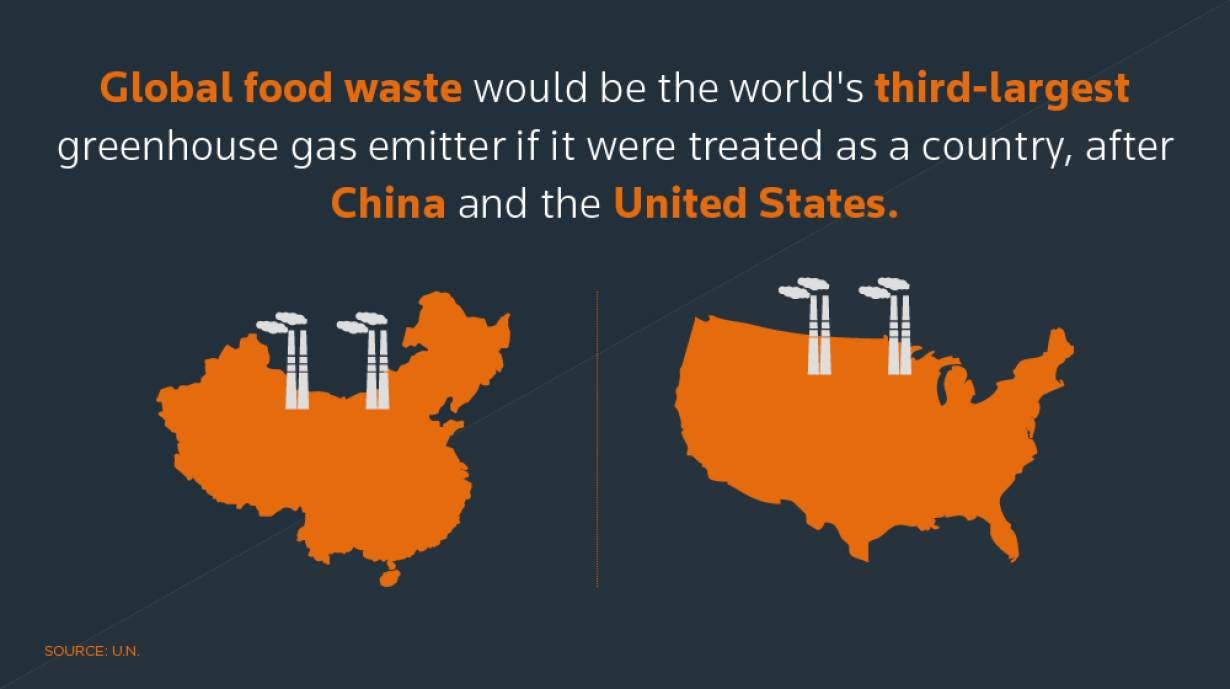

Experts say reducing food waste is not only a moral imperative but a way of curbing emissions of planet-warming gases linked to agriculture which accounts for about 20 per cent of overall greenhouse gas emissions.

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has calculated that global food waste would be the world’s third-largest greenhouse gas emitter if it were treated as a country.

“

Around 10 per cent of the European Union’s fresh fruits and vegetables come from Kenya, and when produce makes it to the airport it gets sorted there for the cosmetic standards.

Robert Opp, head of innovation, World Food Programme

Ugly veg

Thousands of miles away in Kenya, a different kind of initiative is taking root - one that uses produce deemed too ugly for Western supermarket shelves, such as wonky carrots, curved cucumbers and dimpled apples.

Nairobi-based enterprise Enviu aims to turn some 5 tonnes of “imperfect” produce into 78,000 school meals a day under a pilot programme it is developing with the World Food Programme’s (WFP) new innovation hub.

According to the FAO, about a third of all food, by weight, is spoiled or thrown away worldwide as it moves from where it is produced to where it is eaten, costing up to $940 billion per year globally.

“Around 10 per cent of the European Union’s fresh fruits and vegetables come from Kenya, and when produce makes it to the airport it gets sorted there for the cosmetic standards,” said Robert Opp, head of innovation at WFP.

“An estimated 25 per cent of that food, about 75 tonnes a day, is rejected,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Using rejected food would mean farmers no longer losing income and more children getting fed, he added.

“There’s a massive amount of food wasted every year and there’s still hunger, so if we can make the food systems more efficient, reduce the wastage and improve distribution - that’s a good thing for the fight against hunger,” Opp said.

Olympic leftovers

As efforts to cut food waste spread around the globe, athletes at this month’s Rio Olympics will play a part, perhaps without even knowing it.

Refetto-Rio, an initiative by two chefs, Italian Massimo Bottura and Brazilian David Hertz, aims to turn excess food from the Olympic Village into meals for the hungry.

While initiatives like Equoevento or Refetto-Rio are on a relatively small scale, experts say every little helps.

Brian Lipinski, food programme associate at thinktank World Resources Institute (WRI), said piecemeal approaches combined with national policies on food waste were necessary to achieve a meaningful reduction in food waste.

“Maybe the impact from one of these non-profits that are picking up some excess food and donating it is small on its own, but it’s really one of the only ways to go about addressing this sort of waste right now,” he said.

Lipinski also said it was time to stop focusing on how to produce more food for the world’s growing population and instead concentrate on efforts to reduce food waste.

Europe takes lead

In Europe, the European Commission has proposed that member states develop national strategies to prevent food waste by at least 30 per cent by 2025.

Germany has been a leader on the issue. In 2012, the German government launched a “too good for the trash” campaign and the country has also pioneered “food-sharing”, using the internet to distribute produce recovered from store rubbish while still in good condition.

In 2015, France introduced legislation banning big supermarkets from destroying unsold but edible food. Failure to comply could expose supermarket managers to two years in jail and fines of 75,000 euros ($83,850).

And last week Italy passed a law that makes it easier for supermarkets to donate unsold food to charities, in an effort to reduce waste.

“There’s still too little awareness about food around the world,” said de Sanctis while checking his phone to see which of his volunteers had signed up for the next food pick-up.

“People don’t plan what to eat and there’s a lot of waste in people’s homes. We have to educate people about food waste because it’s a real problem.”

This story was published with permission from Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women’s rights, corruption and climate change. Visit news.trust.org