Masaki Takeuchi wants Singapore to dream big.

Specifically, the Japanese architect and civil engineer believes a floating city, created off the shores of Southeast Asia’s smallest country, could provide enough land for an additional 50,000 people and produce enough food, water and energy to sustain them without the need for land reclamation.

This plan was unveiled by Tokyo-headquartered civil engineering firm Shimizu Corporation at the recent International Built Environment Week (IBEW) in September in Singapore.

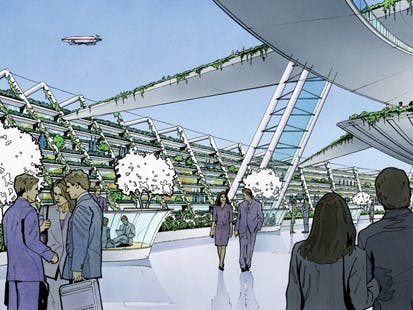

Speaking at the event, Takeuchi said the futuristic Green Float project would be built with steel frames filled with concrete and would float on the sea. Each artifical floating island would feature a 1,000 metre tall, torch-shaped skyscraper that houses homes, a vertical farm and a shopping mall, forming its own city.

The high-tech development would meet its energy needs by generating solar energy in outer space. Called space-based solar power generation, the technology is expected to be commercially available by 2030, with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency currently working on solutions to transmit energy from orbit to earth, he said.

Additionally, generators located around the island will harness the difference between cooler deep and warmer surface seawaters to generate electricity, in a process known as ocean thermal energy conversion.

The man-made island, which is to be three kilometres in diameter, could accommodate both farmland and a lagoon for aquaculture. Seawater could be desalinated through hydraulic pressure to meet residents’ drinking water needs and for irrigation, he said.

Speaking to Eco-Business on the sidelines of the event, Takeuchi revealed that Shimizu was in talks with the Singapore government to launch the project in the city-state by 2050.

“

Twenty years ago, no one would have believed what humans can build today. But 1,000-metre-tall buildings are no longer a dream. Maybe you will live on a floating island one day.

Masaki Takeuchi, senior engineer and architect, ocean programs, Shimizu Corporation

With only 725.1 km² in land area—half the size of Los Angeles—Singapore has been building ever higher skyscrapers and reclaiming land to unlock more space and host its population, which has grown from just over 4 million in 2000 to 5.7 million in 2019.

Takeuchi said: “Singapore has already reclaimed much of the sea space that can be reclaimed, but it will have to go further to ensure continued economic growth. Where waters are deeper than 20 metres, land reclamation is not feasible, and a floating island would be the better and also a cost-competitive solution.”

Tim Risbridger, head of Singapore at global natural and built asset design and consultancy firm Arcadis, said that Singapore should explore all alternative solutions to traditional land reclamation, where the substantial volumes of sand needed were becoming increasingly difficult to source.

Artist’s impression of the city in the sky that features offices, housing and parks. Located an elevation of 1000 metres, residents could also enjoy cooler temperatures than on the mainland. Image: Shimizu Corporation

The project, however, is not without challenges. One obvious problem is that Singapore’s available sea space is severely limited due to shipping routes, the country’s economic lifeline.

Risbridger noted that while shipping lanes could be redirected, the cost and technical difficulties in deploying floating islands would be substantial. He said that the island would require some form of breakwater structure to protect it from the effects of storms, and that it would need to be anchored to the seabed.

There are also environmental issues. Chou Loke Ming, emeritus professor at the department of biological sciences at the National University of Singapore, said floating structures were ecologically less destructive than land reclamation.

“However, (engineers and architects) have to take into account the ecological impact of light deprivation and the reduction of surface area between sea and air for gas exchange,” he said.

Blocking sunlight prevents aquatic plants and underwater life from creating the energy they need to survive, which can harm ecosystems beneath the surface. Placing such a large structure on the water surface prevents oxygen that plants produce from reaching the atmosphere, and reduces the amount of carbon dioxide entering the ocean, he said. Both could affect marine biodiversity and habitats.

He added: “If the floating island is constructed with sufficient gaps allowing sunlight to penetrate through, as well as gaps beneath allowing for air to be in contact with the sea surface, the negative impact can be mitigated.”

His colleague Peter Alan Todd, associate professor at the department of biological science at National University of Singapore, said such massive structures were also bound to affect natural coasts. “Placing a floating structure close to a natural seashore would undoubtedly have devastating effects on coastal habitats and intertidal life,” he said. “It could have local current effects and disturb water flow interaction.”

“You would not want to put the island next to coral reefs, seagrass or mangroves,” he continued. The further the structure is placed away from the coast, the smaller the impact on the environment, Todd predicted, but added that this would require further research and modelling to verify.

Takeuchi said Shimizu had not yet conducted an environmental impact assessment to study the effects of the structure on the environment and will do so once a project and location have been confirmed.

By 2025, Shimizu plans to build the first Green Float in Japan, which will be a downsized version of the project proposed at IBEW, with the skyscraper being only 100 metres in height.

The Green Float is not the first ambitious idea Shimizu has come up with. Five years ago, the firm announced plans to build an underwater city of 5,000 people that draws energy from the seabed.

Takeuchi noted that the structure would ideally be placed near the equator where waters and winds are calm and tropical storms are unlikely to make landfall. And with technological progress, floating cities will be feasible in the future, he shared.

“Twenty years ago, no one would have believed what humans can build today. But 1,000-metre-tall buildings are no longer a dream. Maybe you will live on a floating island one day,” he said.