Sorghum is the fifth most economically important cereal in the world and is grown in some of the most arid parts of Africa and South Asia, where it is a staple food for half a billion people.

The new research finds that for every degree of warming above a 1985 to 2014 average, sorghum crop yields could drop by around 10 per cent. This suggests the hardy cereal may be more vulnerable to heat stress caused by climate change than previously thought, the authors tell Carbon Brief.

However, the indirect impacts of temperature might actually be a larger driver of future sorghum yield declines, another scientist tells Carbon Brief. It is likely that environmental factors, such as humidity, will have significant role in crop productivity, he says.

“

While I do not doubt the ultimate importance of tolerance to direct effects of high temperature, this is a consequence of “shock effects” of high temperature at specific development stages.

Graeme Hammer, director of plant science, University of Queensland

Why is sorghum so hardy?

Sorghum is a tall cereal grain that is grown for food in arid parts of Africa and South Asia, and for animal fodder (and sometimes biofuel) in many developed and developing countries.

According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, the US is the world’s largest producer of sorghum, followed by Mexico, Nigeria, Sudan and India.

Farmers started growing sorghum in north-eastern Africa around 8,000 years ago. Through thousands of years of selective breeding, the crop has evolved to be more resilient to harsh environmental conditions than other cereals, such as maize and wheat.

Sorghum is particularly hardy in dry conditions because it has large fibrous roots which can reach far down into the earth to extract water. It has also adjusted its reproductive system to withstand high temperatures.

As a result, sorghum has even been suggested as an alternative crop for wheat and maize farmers facing falling yields due to climate change.

However, the new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggests that sorghum yields will be severely dented by rises in temperature.

The researchers find that sorghum yields will decline “substantially” at temperatures higher than 33C. Lead authors Jesse Tack and Krishna Jagadish from Kansas State University explain to Carbon Brief in a joint interview:

“We studied 30 years of sorghum production in Kansas and found that the crop is vulnerable to additional heat stress should average temperatures rise. Our results indicate that climatic change will likely produce an average yield loss of 10 per cent for each degree Celsius of warming.”

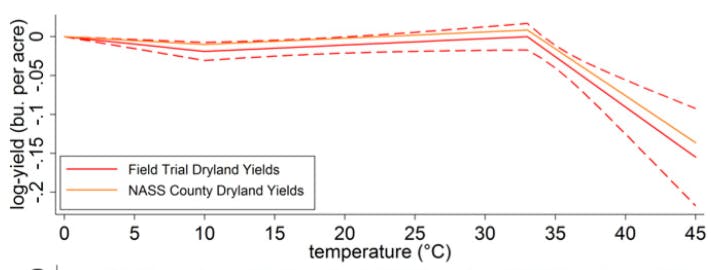

The graph below shows how exposure to temperatures causes negative changes to sorghum yield. The red line shows the results for managed field trials at 11 locations across Kansas, while the orange line shows results for data taken from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS).

Graph shows how exposure to temperatures causes negative changes to sorghum yield (per acre). Red shows the results for managed field trials at 11 locations across Kansas while orange shows results for data taken from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). Dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval. Source: Tack et al (2017)

Growing problems

Using data from 9,000 observations collected over the course of the 11 trials and 30 years, the researchers developed a model to simulate how rises in temperature could affect sorghum yields.

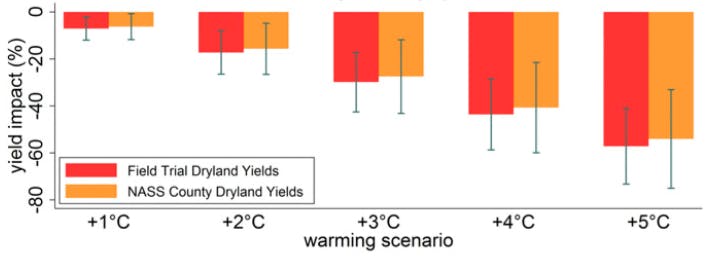

The chart below shows the projected drop in yield for each degree of temperature rise above a 1985-2014 average. So, for example, 2C of warming (roughly equivalent to 2.6C above pre-industrial) could cause sorghum crop yields to drop by 17 per cent. Losses increase to 57 per cent for the highest scenario of 5C.

Chart shows how global warming of 1C to 5C above a 1985-2014 average will impact the yield of sorghum (%). Red shows the results for managed field trials at 11 locations across Kansas while orange shows results for data taken from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). Error bars show the 95% confidence interval. Source: Tack et al (2017)

Warming affects the productivity of sorghum by causing heat stress at key points in its reproductive cycle, say Tack and Jagadish:

“We show that pre-flowering [when reproductive parts are developed] and post flowering stages [when seeds are produced] to be equally impacted by stress. We can do this because we observe planting and flowering dates for every single observation, another valuable aspect of our data.”

However, falling crop yields may also be impacted by temperature-dependent factors other than heat stress, says Prof Graeme Hammer, director of plant science at the University of Queensland, who was not involved in the research.

In his research, he has shown that rising temperature can have a number of indirect effects on the growth and development of cereal plants.

For example, unusually warm temperatures can affect the vapour pressure deficit (VPD) – this is the difference between the water vapour contained in the leaf’s interior and in the air surrounding it.

Hot weather causes increases in VPD (pdf), upping the rate of transpiration – the process by which plant moisture is released into the atmosphere.

In order to readjust this balance and prevent moisture escaping, a plant will close its pores. This restricts how much CO2 the plant can absorb and use to grow through photosynthesis.

Hammer believes that this indirect effect of temperature on plant growth has a larger impact on crop yield than heat stress:

“While I do not doubt the ultimate importance of tolerance to direct effects of high temperature, this is a consequence of “shock effects” of high temperature at specific development stages. The gradual effects of “heat stress” reside in consequences they bring on the dynamic of crop growth and development over the season.”

Finding a solution

Whether the impacts of temperature rise on sorghum yields are predominantly direct or indirect, the need to help farmers adapt is still there.

One solution for US farmers might be to grow sorghum in cooler environments, such as the US corn belt, researchers say.

However, similar options are not necessarily available in hotter, drier countries, such as Chad, where sorghum is a staple food for thousands of subsistence farmers.

Instead, scientists will need to hunt for new genes that promote resistance to heat extremes and incorporate them into sorghum breeding programmes, say Tack and Jagadish:

“Our particular focus was on the potential to adapt using currently available seed varieties. We find limited scope in this regard. However, breeding programmes can likely introduce new genetic material from sorghum plants existing in nature in order to boost heat resilience.”

In addition to developing new heat-resistant breeds, researchers will also have to develop new crop management strategies that address how warming affects the VPD, says Hammer:

“Some attention to adaptation of phenology (time to flowering) of cultivars [plant breeds] and adjustment of crop management (to deal with changes in water balance) would likely moderate much of the effect observed.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.