With the arrival of spring, Platte Farm Open Space, located in the diverse, working-class neighbourhood of Globeville in north Denver, comes alive with native grasses, pollinator gardens that attract bees and butterflies, and wildflowers, such as Mexican hat, asters, poppies, and Gaillardia.

“This is a beautiful amenity — a beautiful piece of space that was previously being abused,” says Jan Ediger, a longtime resident of Globeville. A former brownfield site, Platte Farm is 5.5 acres (just over 2 hectares) of open green space in the heart of Globeville that, along with the wildflowers, grasses, and gardens, has walking trails, a play area for children, and a detention pond to help prevent localized flooding.

Once a dumping ground for trash and industrial pollution in Globeville, the development of Platte Farm Open Space was a 14-year journey — a collaborative effort between the community members of Globeville, the city of Denver, and Groundwork Denver, a nonprofit organization that works to create green spaces to help improve community health.

“A lot of people come through here walking and jogging. That never used to be the case,” Ediger says. “We always had a few people coming through on the way to the bus stop, as a pass-through, but now people come here for exercise. We see kids playing, riding bikes, and their parents come with them.”

Health Disparities and Access to Green Space

Urban greenery, such as the shortgrass prairie of Platte Farm Open Space, benefits people’s health and recreation. But access to nature is unequal for lower-income communities and communities of colour compared to affluent white communities.

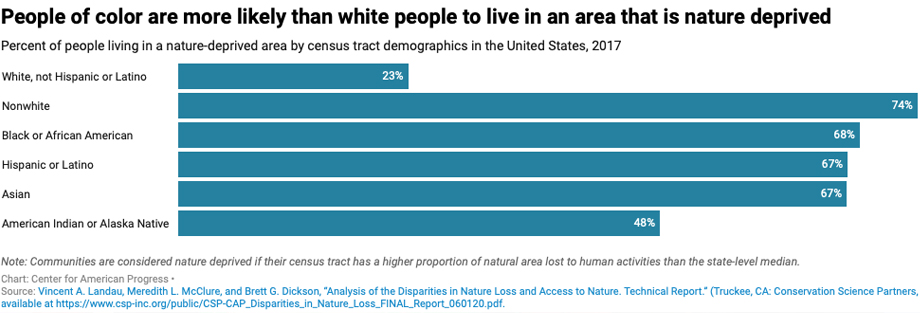

This past summer, the Center for American Progress and the Hispanic Access Foundation released a report finding that communities of colour experience “nature deprivation” at three times the rate of white Americans.

According to the report, 74 per cent of communities of colour live in nature-deprived areas, with Black communities experiencing the highest levels of deprivation.

A report from the Center for American Progress and the Hispanic Access Foundation found that communities of colour experience “nature deprivation” at three times the rate of white Americans. Chart by the Center for American Progress based on an analysis by Conservation Science Partners (CSP).

Meanwhile, in a 2019 study, researchers at the University of British Columbia examined 10 U.S. cities, including New York, Chicago, Houston, and others, and found that Latino and Black communities have less access to urban nature than white communities.

“The widespread green inequities uncovered by this research are serious issues in the context of the effects of urban vegetation on urban health and well-being,” the authors write.

“Urban residents with lower access to urban vegetation, according to our analyses, are also those who are most likely to experience poor public health outcomes that could potentially be mitigated by adequate exposure to urban vegetation.”

In fact, a growing body of evidence shows that access to green space in urban areas can bring considerable benefits to the health and well-being of city residents.

These benefits may include improved cognitive development and functioning, reduced symptom severity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, reduced obesity, and positive impacts on mental health.

Looking forward, the University of British Columbia researchers write, the “impact of urban vegetation exposure on the health and well-being of marginalized communities may become even more critical as climate change worsens.”

“

Since access to places to play — whether it’s team sports at a park or simply hiking in a nature preserve — is positively related to levels of physical activity, such parks and open spaces are important elements in keeping people healthy.

Jennifer Wolch, professor of city and regional planning, University of California Berkeley

She also says these health benefits stem primarily from opportunities for residents to get outside and get active.

“Many epidemiological studies have shown that people who have better access to green space have higher rates of physical activity,” Wolch says.

“One of the key problems facing inactive people is that they are at a higher risk of chronic disease, such as diabetes, chronic heart problems, and sometimes cancers. Since access to places to play — whether it’s team sports at a park or simply hiking in a nature preserve — is positively related to levels of physical activity, such parks and open spaces are important elements in keeping people healthy.”

Resources and Strategic Partnerships

“Platte Farm Open Space really is the epitome of a community-led project,” says Cindy Chang, the executive director of Groundwork Denver.

“The residents of Globeville had a vision for this land as being an open park that anyone in the community could enjoy. This was a unique process because the community was at the table for almost every design meeting, almost every construction stage, and they even helped decide which kinds of trees would be planted. They were involved in the details in a way that Denver has almost never designed a park before.”

Through a process of remediation, contaminated land was replaced with fresh layers of topsoil, and is now home to prairie habitat that attracts foxes, rabbits, birds and butterflies.

The necessary financial resources to make Platte Farm a reality — money for the purchase of the land, remediation of the soil and planning of the site — weren’t always easy to come by.

For example, in 2013, Xcel Energy and the environmental nonprofit WildEarth Guardians concluded a legal settlement in which Xcel agreed to pay Groundwork Denver US$447,000 to fund energy efficiency and other clean energy projects in neighbourhoods in north Denver impacted by air pollution, while channelling the remaining funds toward Platte Farm.

In addition, Platte Farm received a US$550,000 grant from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment to help with the construction and maintenance of the site, bringing the project’s total cost to about US$1 million.

This story was published with permission from Ensia.com. Read the full story.