In 2010, the aviation industry agreed an aspirational goal to cap its emissions after 2020, so that future growth would have to be “carbon neutral”.

This won’t be easy. The industry is expected to grow at an average rate of around 5 per cent per year over the next two decades. This means that it will either have to find a way to drastically increase its efficiency, or balance its own emissions through cuts made in other sectors.

All this takes place in light of the UN Paris Agreement agreed in December 2015, which could soon come into force.

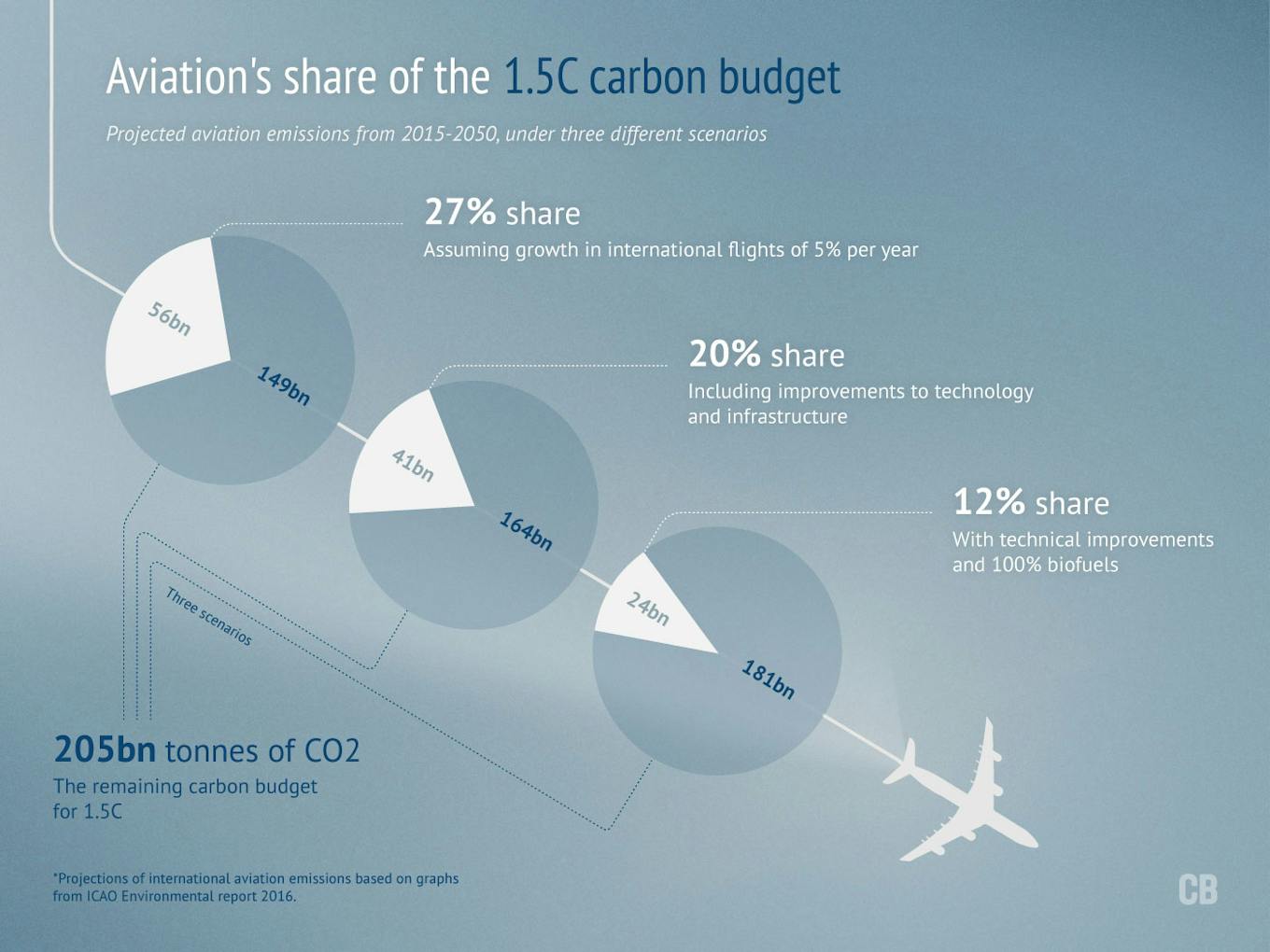

The agreement set a target to limit global temperature rise to 2C above pre-industrial levels, with a tough aspirational goal of limiting it to 1.5C. Analysis by Carbon Brief has shown that aviation could consume a quarter of the emissions budget for 1.5C by 2050.

Infographic: Aviation’s share of the 1.5C budget. By Rosamund Pearce for Carbon Brief.

In 2015, aviation emitted 781m tonnes of CO2, which is slightly more than Germany. If it was a country, it would be the world’s sixth largest emitter.

Despite this, aviation does not feature in the Paris Agreement – as is also the case for shipping. Instead, it has its own UN body called the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). Since 1997, when countries adopted the Kyoto Protocol, this group has been tasked with coming up with a way to reduce emissions from aviation.

Almost 20 years later, it might finally agree on a scheme. From 27 September to 7 October, ICAO member states will meet at its next assembly, where emissions reductions are on the agenda. Stakes are high, as the assembly only meets once every three years — further delays could push back action by years, during which time emissions will continue to rise.

A lengthy debate

It is worth bearing in mind that any scheme will only apply to international flights, as domestic aviation emissions are already included in countries’ national accounting and targets. International aviation is responsible for around 62 per cent of total aviation emissions.

There are various ways in which aviation can reduce its emissions, none of them ideal.

The preference among negotiators is for technical and operational fixes to aircrafts and routes, which will increase efficiency, and increased use of sustainable alternative fuels. Indeed, the sector already has an aspirational goal to improve aviation fuel efficiency by 2 per cent a year.

However, it is acknowledged in the industry and by scientists that tinkering with aircraft efficiency will not deliver the types of reductions required to allow the industry to grow without adding to emissions. Therefore, ICAO is expected to agree some kind of market-based mechanism that would see it buying savings elsewhere to cover its emissions.

The exact nature of this mechanism has been under discussion since the last ICAO assembly in 2013; offsetting and cap-and-trade schemes were both being considered.

Between March 2014 and January 2016, the environmental advisory group of the ICAO Council held 15 meetings to assess these options.

A high-level group met several more times during 2016 to finalise a draft agreement on limiting aviation emissions and incorporating suggestions from individual member states, in order to present an acceptable compromise text for further discussion.

The text

The weight of opinion has now landed behind an offsetting scheme for the aviation industry. This is a significant move: it would represent the first time that a global market-based approach to emissions had been implemented, in any sector.

However, the text is likely to change over the coming two weeks, as states thrash out a compromise over some of the most contentious points relating to the scheme. There will also be more than 30 representatives from NGOs, who will be in Montreal to pressure states into signing up to the most ambitious version of the deal possible.

The schedule is one of the contentious elements of the deal. The text currently divides the scheme into three phases:

- 2021 to 2023 — Pilot phase. States can choose both whether or not to participate, and how much of their emissions their airlines will offset from a menu of options.

- 2024 to 2026 — First phase. This applies to states that participated in the pilot phase, as well as any that voluntarily opt in to this phase. The volume of emissions each airline offsets is prescribed by the agreement.

- 2027 to 2035 — Second phase. All states to participate, apart from Least Developed Countries, Small Island Developing States, and Landlocked Developing Countries (who can still participate if they choose).

There is also a provision in the text to review the CORSIA every three years, starting in 2022, so that adjustments can be made if necessary.

Enabling states to opt out of the deal is a nod towards the need for differentiation, so that developing countries are not disproportionately burdened.

The text as it currently stands states that aircraft emissions are only covered by the offsetting scheme if the route both begins and ends in countries that have volunteered to be part of the scheme. As well as ensuring differentiation this also prevents market distortions, the text says.

Another way of differentiating the deal is the method by which emissions are assigned to each airline.

There are two ways of doing this: individually and sectorally. Both methods take it as read that airlines will have to offset any emissions for which they are responsible beyond 2020 levels. However, they assign responsibility for these emissions differently.

The individual approach is, perhaps, the more intuitive. Here, each airline would have to offset its own emissions beyond 2020 levels.

However, this could be seen as unfair to airlines that are currently small, but are expected to grow dramatically in the years to come, as they will have to offset a bigger proportion of their total emissions compared to airlines that have already had time to grow and develop. Much of the growth in the coming years will be in developing countries, as the UK’s Airports Commission illustrated.

The sectoral approach takes emissions from the industry as a whole and then divides them up between the participating states, according to their rate of growth. An explanatory note by ICAO from earlier this year says:

“While this approach provides operators growing above the global average with less offsetting requirements than their individual growth of emissions, it provides other non-fast growing operators with higher offsetting requirements than the ones they would have otherwise if they were to offset just their individual growth of emissions.”

This story was published by Carbon Brief under a Creative Commons’ License and was republished with permission. Read the full story.