It takes a straight-shooting sort of chief sustainability officer to deal with the slings and arrows of an industry as bewilderingly complex and exhaustingly controversial as palm oil. So it’s just as well that the world’s biggest oil palm trader, Wilmar International, has Jeremy Goon in that role.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

For almost 13 years, the Malaysian has steered the billion-dollar Singapore-listed company through a maze of allegations, from deforestation and burning of carbon-rich peatlands to human rights abuses. A year ago, the company saw its facilities in Sulawesi graffitied and an Indonesian band perform on a refinery roof in a show of rock ‘n roll protest by Greenpeace, which dubbed it “the biggest and dirtiest palm oil trader in the world”.

As the industry’s biggest player, Wilmar is a lightning rod for environmental protest in an industry at the centre of a political and cultural war between Southeast Asia and Europe over an oil that is found in more than half of all the products found in supermarkets, from instant noodles to laundry detergent.

Jeremy Goon, Wilmar’s chief sustainability officer, at a Tropical Forest Alliance meeting. Image: Flickr

Wilmar works with green groups to fulfill the sustainability commitments it has made over the years, but Goon holds a view that is common among his peers. “Certain civil society organisations tend to only really have one tool in their locker—they only know how to campaign.”

“The palm oil industry has made positive changes over the last decade, and not enough credit has been given,” he says, conceding that there are areas where the business needs to improve.

“One criticism [from NGOs] was that we were not transparent enough in how we monitor our suppliers,” says Goon, pointing to a commitment the company made last December to cut deforestation out of its labyrinthine supply chain by 2020 by using satellite technology and third-party verifiers to monitor land use change—a first for the industry—after the Greenpeace campaign (Greenpeace has said the policy won’t work because its suppliers are not mandated to supply maps of their concessions).

“

I woke up at 6.30am to hear that a rock band was playing on top of our refinery.

“We are monitoring 14.75 million hectares of plantations. It’s a mammoth task. It’s much more complicated than just saying we’ve got satellite images of our suppliers’ plantations. You can have satellite imagery, but it’s still very difficult to say conclusively that a certain supplier is or isn’t deforesting,” says Goon. Wilmar’s conservation advisor Ginny Ng wrote about these challenges in an opinion piece in September.

Of the positive changes the industry has made, such as introducing no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation (NDPE) policies and publishing the names of its suppliers to bring some much-needed transparency to the sector, Wilmar has been at the forefront of many of them.

But Goon is realistic about how far the palm oil industry can go to clean up its act without other less visible companies taking action too. “There’s the question as to whether companies are getting on or off the sustainability train. Some never got on it to begin with. It’s very difficult to get everyone involved.”

“It’s easy to find outlets for unsustainable oil. To some companies, it [sustainability] just doesn’t matter,” he says.

As the worst haze season since the great peatland fires of 2015 choked Southeast Asia this year—10 per cent of the 346,000 fire alerts in Indonesia were in palm oil concessions, and 2,556 of those were on Wilmar land, according to June to October 2019 Global Forest Watch (GFW) data—and the time approaches when the European Union will ban palm oil for biodiesel because of the industry’s links to deforestation, no one knows better than Goon that a lot of work remains to be done.

In this interview with Eco-Business, he talks about the challenges of implementing Wilmar’s most far-reaching sustainability commitment, how the recent haze outbreak affected those commitments, his hopes for the sustainable palm oil market, and the experience of waking up to a rock band playing on top of his company’s refinery.

Wilmar has had yet another colourful 18 months in its 28-year history. Greenpeace protests on your refineries in Indonesia a year ago, then a major declaration to develop a deforestation-free supply chain by 2020 the following month, which covers about 1,500 plantations, 750 mills and 24 million tonnes of oil palm. How do you see your sustainability progress?

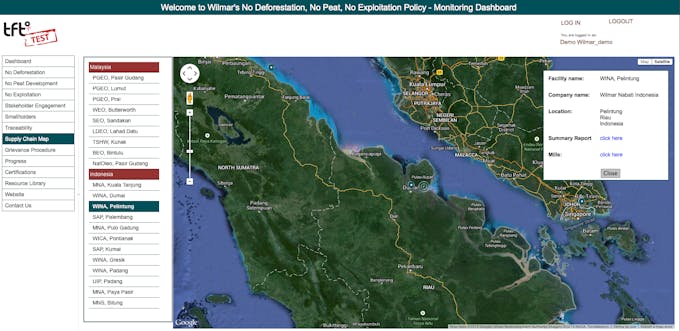

Our sustainability journey started a long time ago. We were the first to come up with a No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) policy in 2013, which applied to third party suppliers as well as our own supply chain. In 2015, we published a sustainability dashboard, showing traceability back to 1,000 mills—that was another first.

Wilmar’s sustainability dashboard lists and locates all its palm oil mill suppliers in Indonesia and Malaysia [click to enlarge]. Image: Wilmar

I should make it clear that we came up with the sustainability dashboard without any campaigning pressure from NGOs. We don’t only act when we’re campaigned against. We act because we cannot deny that climate change is happening, and there’s been an upsurge in haze and erratic weather patterns. We are much more aware of these issues now than we were 20 years ago, and we have to adapt our business.

In December 2018, Wilmar committed to weed out rainforest destruction and labour abuses from its supply chain of hundreds of mills and millions of hectares of plantations. What have been the key challenges in seeing this commitment through?

It’s a challenge to get information on our suppliers without breaching any directives or stepping on anyone’s tail.

We’ve been quite successful at getting concession data from most of our suppliers. We’ve got data coverage of 80 per cent of our suppliers, where we can confidently say what concessions they own and where they are.

But Indonesia issued a directive that rules that companies can’t share any information on their plantations. We’ve had to find a way to work around these roadblocks.

Aidenvironment [Wilmar’s consultancy partner for its new no-deforestation policy, which has worked with the company since 2014] already have a lot of this information. In the past they’d be able to go to government agencies and get concession maps and boundaries. Now, this particular source of information has been cut off.

What was it like to deal with the Greenpeace action?

It made life very interesting. I woke up at 6.30am to hear that a rock band was playing on top of our refinery. My words to my team were: ‘Just make sure we deal with this in a calm, orderly fashion.’

Drone image shows rock band Boomerang perform on top of a silo at the Wilmar International refinery in Bitung, North Sulawesi. Image: Greenpeace

Getting wound up wasn’t going to help. We knew that Greenpeace gets mileage from stunts like this, and not trying to collaborate productively wouldn’t work. Different players have different business models, and campaigning is theirs. But why should campaigns be launched against the companies that are actually trying?

Do you think your competitors will introduce the same zero-deforestation policies as Wilmar?

Walking our talk is one thing. Every player should be doing more. But none of our peers has agreed to do what we did in December. They were happy for us to take the heat from Greenpeace. But now the directive to prevent companies from sharing their concession maps has made it difficult [for other companies to do the same].

Changing the industry is a tall order, particularly when a range of stakeholders have varying commitments. Take the banks. Palm oil is one small business out of thousands that they work with, so they don’t have the same level of commitment [as palm oil companies themselves to tackle deforestation]. If the pressure gets too much, they’ll simply walk away.

Then there’s the consumer goods manufacturers. Some are now saying they use less palm, or don’t use any palm at all. It’s difficult to get the same level of commitment from everybody and get everyone to move at the same pace.

“

Most palm oil companies have standards that we adhere to. But we only hear about the non-believers, and they’re not the majority of the industry.

When we launched our NDPE initiative in 2013, some in the sector said, ‘are you mad?’ Then over the next 18 months, others followed. We brought it to the next level in December 2018. Some didn’t like our suspend then engage policy [Wilmar will suspend purchases from suppliers that violate its NDPE policy and have a system that ensures they do not re-enter its supply chain if the re-engagement protocol has not been fulfilled]. Maybe the wording was a bit sensationalist—some stakeholders didn’t like the language.

Have you gained any new customers as a result of your new no-deforestation policy?

No. Our business was so big to begin with, and there are no customers out there that we don’t already have an existing relationship with.

What’s the toughest thing about growing the sustainable palm oil market?

The biggest issue is the ‘leakage market’—the players that have no sustainability commitments [and sell to customers that do not ask for sustainable product]. If we stop buying from them, and all the other [major] players have the same level of commitments as us, they would have to change. But if not, they’d just go elsewhere. There is very little incentive for them to change.

To some companies, sustainability just doesn’t matter. Indonesia is the single largest producer of palm oil, and it’s easy to find outlets for unsustainable oil—which is a 10 million-tonne market.

“

Fire poses a threat to our operations on a whole and the use of fires in our oil palm plantations is a major risk; akin to us burning our source of income.

Another issue is certified sustainable oil. RSPO [the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, the industry’s largest certifier] has set the standard [for sustainable palm oil] so high, and keeps moving the goalposts every six months. That’s probably why we’ve not seen any new producer members of RSPO in the last six years.

Growers that started plantations 10 years ago may have done many things that were against RSPO rules, such as planting on peat. To get certified, they’d need to pay compensation. That’s a real barrier for new members, which is why we are unlikely to see bigger volumes of certified oil.

What’s your view of the image of the palm oil industry right now?

Truth be told, it’s not in the best place. At times, yes, the negative campaigns are justified. But there are many good things that are overlooked or not spoken of. In every country and industry, there are good and bad actors. For some reason, this industry has been demonised more than any other.

Most palm oil companies have standards that we adhere to. But we only hear about the non-believers, and they’re not the majority of the industry.

Given the recent haze outbreak in Indonesia, which heavily impacted Wilmar’s concessions according to GFW data, what does that say about the effectiveness of Wilmar’s new sustainability policy?

The GFW reports indicate hotspots, where temperatures appear to be higher than its surroundings. This however does not represent the number of actual, verified fires on the ground.

Between January and September 2019, there have been 77 verified fires in Wilmar-owned plantations and 135 verified fires within a 5km range outside of our concession boundaries. In comparison, as you mentioned, GFW indicated there were 2,556 “fire alerts” in Wilmar-owned concessions.

Fire poses a threat to our operations on a whole and the use of fires in our oil palm plantations is a major risk; akin to us burning our source of income.

Wilmar has always made a strong stand against the use of fires in our operations. We established a ‘No Burn Policy’ that precedes and later became an integral part of our NDPE policy.

Just as important as our fire management efforts and strategies is the need for community engagement and awareness on the risks surrounding the use of fires for land clearance and preparation as well as enforcement efforts to deter or apprehend those that intentionally start fires.

![A new Greenpeace International investigation has revealed that Wilmar International, the world’s largest palm oil trader, is still linked to forest destruction for palm oil almost five years after committing to end deforestation.[1]](https://eco-business.imgix.net/ebmedia/fileuploads/GP0STS4V5_Web_size.jpg?ar=16%3A10&auto=format&fit=crop&ixlib=django-1.2.0&q=85&width=320)