But, as the world attempts to curb its greenhouse gas emissions, its increasing interconnectedness can complicate matters.

A key debate is who should be held responsible for greenhouse gas emissions of internationally traded goods. In a globalised economy, should responsibility for emissions lie with those that produce goods?

Or should it rather be accounted for by those that consume final goods and services?

In a new paper, published in Global Environmental Change, we suggest that an exclusive focus on producers or consumers falls short as a method of allocating trade-related emissions to individual countries.

Instead, we propose an accounting scheme that divides trade-related emissions among trade partners in proportion to the economic benefits they derive from these emissions.

Where should emissions be counted?

Traditionally, emissions are attributed to the country where they are released. This is the “production-based accounting” (PBA) method used by governments to report their greenhouse gas “inventories” to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

However, products manufactured in one country are often consumed elsewhere. This prompts the question of whether the producer or consumer should take responsibility for the emissions associated with that product.

Take the example of a cotton T-shirt that is produced in India and then shipped to, and sold in, the UK. Growing and processing the cotton produces greenhouse gases, as will the factory where the garment is made.

As manufacturing in many sectors has increasingly shifted from developed to developing countries, a PBA approach means the associated emissions have also shifted. In the case of the T-shirt, it means India counts the emissions rather than the UK.

There is a long-standing concern that countries could use this approach to meet their commitments to reduce emissions by merely shifting the production of carbon-intensive goods and services elsewhere.

As production in rich countries is usually less carbon-intensive, this also risks “carbon leakage” – where production is moved to countries with fewer environmental controls, thus causing an increase in emissions.

A “consumption-based accounting” (CBA) method instead counts emissions for a product or service where it is used. In the T-shirt example, this would be the UK.

Under a CBA method, richer countries would generally take responsibility for substantially more emissions compared to PBA, while poorer countries would take a smaller share.

But would it be fair to let firms in rich countries off the hook and exempt them from climate regulation if they export their own products? And do firms in poorer countries not also benefit to at least some degree from making the products they sell in foreign markets?

It is this debate that our new approach aims to help solve.

Allocating emissions

The economic logic behind our “economic benefit shared responsibility” (EBSR) approach is simple. Both producers and consumers benefit financially by not paying an economic cost related to the impacts that their greenhouse gas emissions have on society.

If a carbon price – such as a global carbon tax – reflecting the social cost of carbon emissions was introduced, this financial “surplus” of both producers and consumers would shrink.

In other words, producers and consumers both derive a benefit from emissions generated below the optimal carbon price at the expense of those who bear the impacts of climate change.

But how is this benefit distributed between producers and consumers? The size of the producer- and consumer-surplus depend on the slope of the supply and demand curves, which in economic terms is called the “elasticity” of supply and demand, respectively.

Put simply, it can be understood as describing how easily producers and consumers can react to price changes.

It is well known from economic theory that the burden of a tax – and, in this case, the benefit of not having it in place – is shared between producers and consumers in inverse proportion to their elasticities. That is, those that can more easily adapt to price changes are less affected by a tax.

Take an example where a low-carbon alternative for a carbon-intensive production technology is available at a reasonable price.

In this case, producers can react to a carbon price by increasing the price of their products by less than they would have done if no viable alternatives to emission-generating activities were available.

Likewise, consumers can substitute some types of goods for others – for example, for certain luxury goods – whereas this substitution is harder for necessities, such as food.

That is, those regions with low elasticities of demand or supply, respectively, would have to bear the largest impact of a price increase, whereas those with high elasticity can at least to some degree substitute away and would hence be less affected.

For this reason, regions with lower import and export elasticities benefit more from the absence of an emission price and are hence assigned a higher share of the emissions associated with their foreign trade relations.

For the extreme cases of totally fixed supply or demand, the benefits of not having a carbon price in place would fall on producers or consumers, respectively. Our EBSR scheme would then be equivalent to PBA and CBA, respectively.

Attributing responsibility for trade-related emissions

We test our approach using a multi-regional input-output database combined with elasticity estimates from previous studies and use an example carbon price of $50 per tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2).

To simplify the analysis here, we only discuss trade relations of the five major emitting trading blocks – namely China, India, Russia, the EU and the US. (More detailed results are in the paper.)

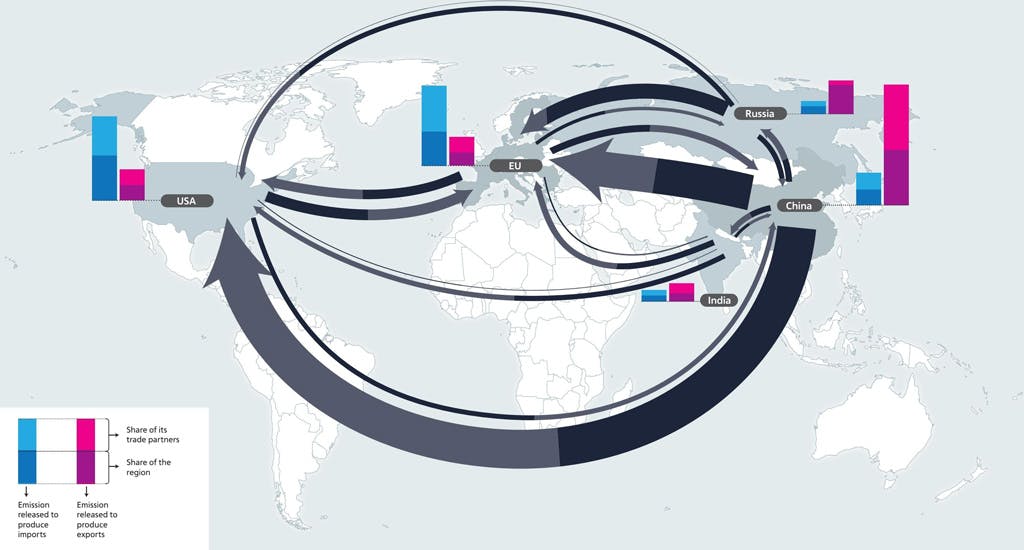

In the figure below, the thickness of the arrows indicates the quantity of emissions generated in one country for exports to another. With PBA, these emissions would be fully attributed to the exporter, while with CBA, they would be fully assigned to the importer.

Responsibility for trade-related greenhouse gas emissions under the EBSR scheme. Arrows denote responsibility for emissions assigned to exporters (dark areas) and importers (light areas), respectively. Blue and pink bars show responsibility for imports and exports, respectively. Results are shown for the five regions featuring the highest trade-related emissions (sum of emissions released for the region’s imports and exports). Source: Jakob et al. (2020).

Under our EBSR scheme, the emissions are divided between importers and exporters as indicated by the light and dark arrow shadings.

For most country “pairs” – an importer and an exporter – trade-related emissions are shared relatively evenly between producing and consuming nations, with exporter shares in the range of approximately 40 per cent to 60 per cent. A notable exception is Russia, which is attributed to more than 85 per cent of its export-related emissions.

This observation is due to the country’s low export elasticity, which is most likely due to the economy’s pronounced dependence on commodity exports – such as oil, gas, minerals, timber and agricultural products – with little potential for substitution.

The bars in each region denote emissions generated for the respective region’s imports (blue) and exports (pink).

Under CBA, countries would be responsible for the emissions associated with their imports (entire blue bar), but not for those emissions related to exports.

Likewise, under PBA, countries would be responsible for the emissions related to their exports (entire pink bar), but not those emissions related to imports.

By contrast, EBSR assigns a certain share of emissions associated with imports, as well as exports to each country (sum of dark shaded pink and blue bars).

National emissions accounting

The choice of accounting scheme has important implications for national emission accounts. For instance, under CBA, the accounts of the US and the EU would be adjusted upward by 15.8 per cent and 18.6 per cent, relative to PBA, respectively, to account for all emissions that were generated to produce these two regions’ imports.

Under our proposed EBSR scheme, only a part of these emissions would be attributed to the US and the EU, and the remainder to their trade partners.

For this reason, the upward adjustments for both would be more moderate, namely 8.3 per cent for the US and 7.2 per cent for the EU.

In general for industrialised regions, EBSR results in greater responsibility for emissions than PBA, but a lower one than CBA.

That is, for these countries EBSR would adjust emission accounts upwards compared to the current practice territorial accounting, but not as much as CBA.

On the flipside, low-income countries would be responsible for some of the emissions generated in the production of exports destined for richer countries.

For instance, whereas CBA would adjust China’s emission account down by 12.5 per cent relative to PBA, the adjustment with EBSR only amounts to 7 per cent.

Overall, for low-income regions, EBSR tends to result in lower responsibility for emissions than PBA, but higher one than CBA.

Why is this important?

Our results could help to open up a new perspective on how to account for trade-related emissions.

This would help move the conversation away from a polarised focus on the responsibility of either producers or consumers and towards a more nuanced and quantifiable approach that recognises that both sides of the trade are jointly responsible.

Our proposed scheme to divide emissions in proportion to the benefits of emitting without having to pay the full social costs of these emissions constitutes a plausible – although not the only – way to divide responsibility.

Due to the substantial data requirements and the associated politicisation of data collection, the proposed EBSR scheme is unlikely to be applied straight away as a basis for international negotiations.

However, it could nevertheless provide an important contribution to arrive at a more comprehensive picture of responsibilities for trade-related emissions.

This story was originally published by Carbon Brief under a Creative Commons’ License and was republished with permission.