As pressure ramps-up to drastically shrink the carbon footprint of the world’s cities, developers and architects have been tinkering with the recipe for the type of materials that goes into a building. City-planners are banking on technology to make cheaper and greener steel and concrete, to drive down the hefty emissions of built infrastructure.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Building and construction are responsible for 39 per cent of all carbon emissions in the world, according to the International Energy Agency. Concrete, the primary component for most built infrastructure, is responsible for a huge amount of greenhouse gas emissions. The five billion tonnes of cement produced each year account for eight per cent of the world’s man-made carbon dioxide emissions. It would rank third for its emissions if it was a country. Then there is steel — whose production accounts for around seven per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

As countries look to slash their emissions, hard-to-abate sectors like construction are facing more heat with governments joining hands and forming coalitions to signal that, moving forward, they will shift to buy low-carbon steel and concrete for public construction.

At the COP26 landmark climate summit in Glasgow, the governments of the United Kingdom, India, Germany, Canada and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), under a new coalition named the Industrial Deep Decarbonisation Initiative (IDDI), pledged to support the use of low-carbon materials in building construction. “If you make it, we will buy it,” said the five nations in a statement.

The member governments of the IDDI plan to reveal interim targets by mid-2022, to better align their procurement plans with new net-zero goals for the public construction sector. The pledge also includes requirements for members to disclose the carbon embodied in major public construction projects by 2025, said the UK COP presidency in a press release.

Within the next three years, the IDDI aims to have at least 10 countries commit to purchasing low-carbon concrete and steel.

Large steelmakers clean up their act

The public procurement of steel and concrete in the five nations currently represents between 25 to 40 per cent of the domestic market for such materials. Industry stakeholders said that the pledge is a clear market signal from some of the world’s largest steel and concrete buyers believing that it will create green demand across the supply chains of the building sector.

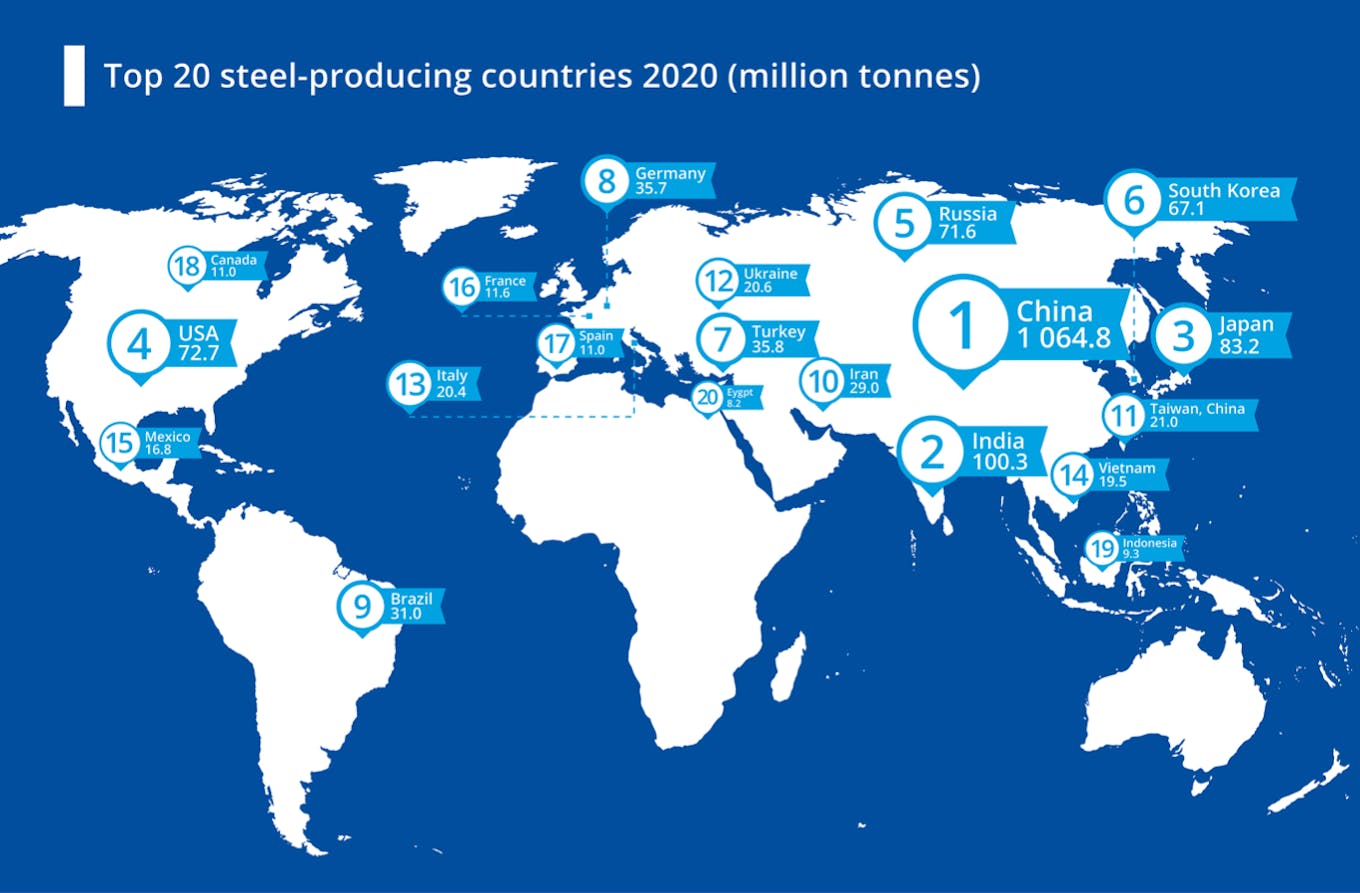

China, India and Japan are the world’s top steel producing countries. Image: World Steel Association

“Global construction accounts for 39 per cent of total global emissions, with buildings equivalent to the size of Paris being built every week. There is now a critical and narrow window for sector transformation,” said Jo da Silva, global director of sustainable development at Arup, a London-based engineering, architecture and city planning consultancy.

“Governments need to make companies feel confident about investing now in the processes of making low-carbon steel and concrete,” she said.

China, the world’s largest steel and concrete producer, is missing from the IDDI list. However, its top steelmaker, the China Baowu Steel Group Corp., formed its own global alliance with other steel producers last Thursday, in a bid to gather resources and exchange information in the development of low-carbon metallurgical technology.

China’s Baowu Steel Group Corp., the world’s largest steelmaker, initiated the formation of a global alliance of steel producers last Thursday, in a bid to gather resources and exchange information in the development of low-carbon metallurgical technology. [Click to enlarge] Image: World Steel Association

Known as the Global Low-Carbon Metallurgical Innovation Alliance, it has more than 60 members from 15 countries. These include leading global steelmakers and mining enterprises such as Luxembourg-based ArcelorMittal, German conglomerate Thyssenkrupp and Melbourne’s BHP Group. About 20 Chinese steel companies are also part of the alliance.

Baowu has committed to carbon neutrality by 2050, a decade earlier than the Chinese government’s national target.

Neil Martin, chief executive for property developer Lendlease’s European business, told Eco-Business that the commitment from steel producers and national authorities to seize decarbonisation opportunities is a potential game-changer for the building sector.

Need for sharper approach on embodied carbon

Lendlease currently uses a large amount of steel - what amounts to a volume sufficient for the building of 60 Eiffel Towers per annum - for its global projects. Substituting the material will make a difference for the environment, given how dirty the steel industry is.

The developer targets to be completely net zero by 2040.

“Property developers have made progress in reducing the operational carbon emissions of buildings, but here’s the rub: almost 90 per cent of building emissions are Scope 3 - indirect emissions from the production of building materials along the value chain. We still have to buy a lot of steel, concrete, aluminium and glass, but we do not have control over their production and supply lines,” said Martin.

Currently, much of the push towards greener buildings is devoted to minimising the energy needed to keep them running, but the situation is changing. During COP26, architects, mayors and property developers have been calling for green building certifications that take embodied emissions from materials into account in order to meet net-zero carbon goals.

Traditionally, steel is made by heating and melting iron ore in a blast furnace at high temperature. A by-product of the chemical reaction that takes place is carbon dioxide. Now, there are several other production methods that are cleaner, involving renewables and green hydrogen. These processes, however, are at various stages of development.

Professor Lam Khee Poh, dean of the National University of Singapore’s School of Design and Environment, and its Provost’s Chair Professor of Architecture and Building, said that strong signalling from national actors to industry matters and governments need to go beyond changing their public procurement models.

“

We need not and should not regard our predominantly steel and concrete jungles as the norm for cities.

Professor Lam Khee Poh, Dean of NUS School of Design and Environment, Singapore

“It is not just that the public sector is often a major customer. Yes, there are economies of scale to be gained, but more importantly, the demonstration of leadership from governments has an impact on the enactment of building codes and standards that will pave the way for a green transition,” he said.

Lam, a strong advocate for net-zero cities, said that building industries around the world typically work to existing regulations and only a handful will adopt voluntary standards to advance the field.

According to COP26 reports, between 2015 and 2020, 19 additional countries have building energy codes in place. However, most construction will still take place in countries without such codes.

“The building sector has historically been fragmented. It will take a revolutionary effort to develop a broadly accepted and comprehensive method of calculating embodied carbon that can be effectively and efficiently implemented in the design process for change to happen,” Lam said.

Better pricing for low-carbon building materials

In Southeast Asia, there is also a need to overcome the biased perception that concrete is cheap, which leads to the inertia to replace concrete use in buildings. The low cost of concrete is mainly due to the use of cheap labour in developing countries, and does not take into account the spillover costs when the production of concrete creates externalities - negative impacts on the environment, said Lam.

Referring to a recently-published McKinsey report, Lam argued that products such as carbon-cured concrete, if positioned differently, can potentially give companies an edge among environmentally conscious buyers and greater pricing power.

Timber as an alternative material should be considered too, especially for tropical cities. “We need not and should not regard our predominantly steel and concrete jungles as the norm for cities,” he said.

Yvonne Soh, executive director of the Singapore Green Building Council, told Eco-Business that the council has recently observed that there is no cost premium for using greener concrete in buildings in Singapore, based on current standards.

Soh also noted that lower-carbon options, whether concrete or steel, are already available.

“In fact, there is a lot of interest among private sector players and many are ready to take the leap to try out new materials. We do not have a lack of willing early adopters,” she said. “The key issue is regulatory barriers, because there are basic safety requirements governing the usage of structural materials in a building.”

“Building professionals must also be comfortable with using the material,” she said, drawing parallels to how governments have educated the public on the safety of the Covid-19 vaccines before they pushed for widespread adoption. “It’s not just about sticking some wallpaper on the wall. We have to ensure that [the use of low-carbon materials] does not compromise the building’s structural safety.”

The Singapore Green Building Council now conducts courses on sustainable supply chains for buildings, to encourage firms and stakeholders in the built environment sector to address environmental gaps in their sourcing and reporting. The council also initiated a pledge for the built environment industry to act on embodied carbon. As of November 2021, more than 75 organisations have signed up.