The Indonesian government has approved a plan to build what has been billed as the world’s largest tidal power facility in the ecologically rich Indonesian island of Flores.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

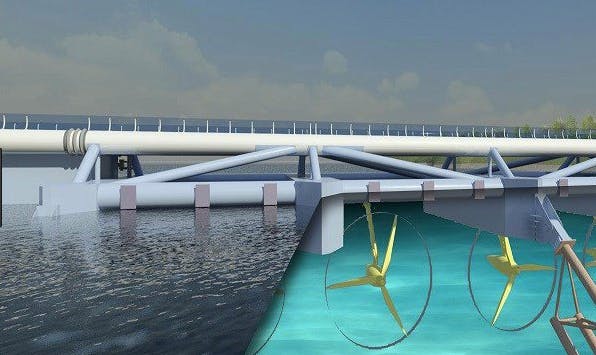

The new plant, known as the Palmerah Tidal Bridge, will be built into a floating 800 metre-long bridge on the Larantuka Strait in East Flores, and promises to deliver power capacity of 18 to 23 megawatts (MW), providing enough electricity for 100,000 people in the area. It is the first deal to emerge from a strategic hydropower alliance between the Indonesian and Dutch governments.

A second phase of construction could see capacity increased to 90 to 115 MW, enough power for more than half a million Indonesians in a region that largely relies on polluting diesel generators for electricity.

An artist’s impression of the Palmerah Tidal Bridge. Image: Tidal Bridge BV

Environmental group Greenpeace has said that it approves of the project as an alternative to coal in fossil fuels-dependent Indonesia, but that caution is needed to ensure that the biodiversity of the marine environment is not affected.

Tidal power is a relatively uncommon form of renewable energy that harnesses the energy of marine currents, a potentially more reliable power source than wind or the sun. The International Energy Agency estimates that in 2014, global tidal power capacity was about 0.5GW, compared to 128GW of solar and 8.8GW of offshore wind.

Indonesia is an ideal location for tidal power, because of strong ocean currents that move between the world’s largest archipelago’s thousands of islands. The Larantuka Strait between Flores and Adonara is one such area, with a number of sites now being considered by the Indonesian government.

The Palmerah Tidal Bridge is also being trumpeted as a way of improving grid connectivity in the eastern part of Indonesia, and giving people in the area better access to education, healthcare and job opportunities.

The project has been awarded to Tidal Bridge BV, a joint venture between Dutch engineering firm Strukton International and venture capital fund Dutch Expansion Capital. It is slated to be completed by 2019 at a cost of US$550 million.

The companies behind the project claim Palmerah Tidal Bridge will be the largest tidal power facility in the world. However, South Korea’s Sihwa Lake Tidal Power Station, with power output of 254 MW, has around double the capacity of the Palmerah project, as does the Rance Tidal Power Station in France, with power capacity of 240 MW.

Greenpeace Indonesia climate and energy campaigner Hindun Mulaika told Eco-Business that the organisation supported the development of renewable energy in Indonesia, a country that is a big coal extractor and user, and continues to approve plans to build new coal-fired power plants to meet its growing energy demands.

Around 50 million Indonesians are without reliable electricity, and president Joko Widowo’s 35,000 MW plan to electrify the country is slated to use mostly coal (20,000 MW, or 57 per cent) to deliver power to those without it.

A report by Greenpeace released in January predicted that if plans to build new coal power plants go ahead in Indonesia, it will suffer more deaths as a result of air pollution than any country in Southeast Asia.

Hindun said that the group “supports the development of renewable energy to foster the transition away from huge coal dependencies in the country.”

“We found a perfect example in Palmerah Tidal Power Plant where the energy source can be found in local resources, which will surely cut distribution costs that commonly occur in big centralised power plants,” she noted.

”But for any renewable project that is developed in Indonesia, it needs to be based on comprehensive research, in this case fish passage design for the tidal bridge and power plant development for the mitigation measures,” she said.

“The project design and its implementation should consider and ensure it does not harm the environment and biodiversity, particularly marine mammals, turtles and whale sharks and their ecosystems,” added Hindun, stressing that the environmental assessment of this project should also take into account migration routes of fish and other marine mammals.

The tidal plant should also allow fishermen to pass through the straight easily, and consideration is also needed for the potentially increased sedimentation above and below the dams, so as not to impact local fisheries, she said.

Eric van den Eijnden, chief executive officer, Tidal Bridge, told Eco-Business that research had been done to assess the environmental impact of the bridge on biodiversity in the area, and that the consequences would be “very limited”.

He said that water speed would decrease as a result of the bridge, but this has “no known” environmental consequences.

Eco-Business has requested for Tidal Bridge BV to share the results of its research, including the likely impact on local communities. The company has yet to produce its findings.

Van den Eijnden added that fish mortality at the hands of the massive turbines that power the plant would be “negligible” because the turbines are “fish-friendly”— designed to prevent fish from being crushed when they pass through it.

Van den Eijnden added: “[Local] fishermen are very enthusiastic because we respect the shipping lanes and they can use the electricity to build cool cells. With this [electricity], they are able to freeze the catch and are thus able to build up a proper industry.”

Tidal power has proved to be controversial in Korea, home of the world’s largest tidal power plants, despite the technology’s renewable status.

Environmental groups and fishermen in Korea have predicted that large tidal power plants will bring about deep and lasting harm to tidal ecosystems, fisheries and the landscape. They have also complained about a lack of environmental impact studies to investigate the potential impact of tidal power plants.