In recent years, the gas industry has zealously pushed the narrative that gas is a climate-friendlier alternative to carbon dioxide-belching coal. As the region shifts to a lower-carbon economy, gas is fast becoming cemented as a ‘bridging fuel’, supplementing intermittent renewables.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

It’s a sales pitch that reflects the sector’s frantic attempt to gain ground in its last big growth market as tougher climate policies and increasingly competitive clean energy solutions begin to cast doubt on the fuel’s long-term political and economic feasibility.

Wood Mackenzie, a consultancy, forecasts the continent will represent 60 per cent of global gas demand growth over the next three decades, with the largest increase expected in emerging markets across South and Southeast Asia. By 2050, it predicts that a third of all fossil gas will be gobbled up by the region, up from 22 per cent last year. China and India propelled demand last year exceeding pre-pandemic levels as the two giants looked to kickstart their economies. China is now the world’s top gas importer.

Most fossil gas consumed around the world is at present transported through pipelines, though a growing share of global trade—12 per cent as of last year—is in liquefied natural gas (LNG). Asia accounts for almost three-quarters of global liquefied natural gas LNG imports, according to AllianceBernstein, a financial firm.

In 2019, gas supplied 33 per cent of Southeast Asia’s electricity, with Thailand being the top LNG consumer, followed by Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Vietnam and the Philippines are the region’s emerging buyers, drawing enthusiastic industry players determined to be part of the expected infrastructure push from around the globe.

Vietnam will start importing LNG via its Hai Linh import terminal this year. It is the vanguard of a myriad of new ports, regasification facilities, pipelines and power plants slated to come online in the coming years. The country had nearly 93 gigawatts (GW) of LNG-fuelled power projects on the drawing board as of last year, while the Philippines currently has 10 such ventures with nearly 11 GW of generation capacity at various permitting stages.

ASEAN total primary energy supply (2019), ASEAN Energy Database. Image: Eco-Business

Market participants are jostling for a slice of the pie. A recent analysis of the industry’s advance into Vietnam by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), an energy finance think tank, believes that the current market frenzy and associated diplomatic pressure are unprecedented in the Southeast Asian country’s power sector.

Most of the noise has come from big ventures involving LNG sourced from the United States and American corporates such as ExxonMobil, AES Corporation and General Electric. Domestic players including subsidiaries of state-owned oil and gas company PetroVietnam as well as South Korean and Japanese energy firms are also in pursuit. Most companies pursuing LNG projects in the country hail from Japan, including names such as Tokyo Gas, Sojitz, Kyushu, JERA and J-Power.

Vietnam’s Gas Power Capacity To Quadruple by 2030. Source: Draft National Energy Master Plan (December 2020), Ministry of Trade and Industry. Image: Eco-Business

Meanwhile, hydrocarbons continue to generate substantial revenue for the public purse. In Malaysia, the fifth-biggest gas exporter globally, income from state-owned oil and gas company Petronas made up about a third of public revenue in 2019, while Brunei Darussalam relies on oil and gas sales for 90 per cent of its exports. As the current chair of ASEAN, the kingdom has actively sought to advance the role of gas in the energy transition.

‘Lobby and lie’

Traditional suppliers of piped gas from across the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have been no less ambitious in their plans to develop new gas infrastructure. The Asean Council on Petroleum (ASCOPE), a regional advocacy group comprising the heads of Southeast Asia’s government-owned oil companies, has worked resolutely to influence legislation to deploy a network of pipelines spanning the region.

A steady presence at high-level energy meetings involving Southeast Asian state officials, ASCOPE has stressed “the importance of fossil fuels” in powering the bloc’s economic growth, advocating the “benefits of natural gas within the region’s energy mix”, and the role of gas in the energy transition. At nearly 4 per cent per year, the region’s fossil gas demand growth has been second only to that of renewables, a trend governments may be keen to maintain.

Besides Vietnam, the Philippines has been among those heavily targeted by industry lobbying. The United States Department of State, through its Asia EDGE (Enhancing Development and Growth Through Energy) Initiative, has reportedly pushed legal and regulatory reforms in the country to stimulate the creation of a new market for American LNG exports, with the archipelago’s only domestic source of fossil gas predicted to run dry this decade. American oil and gas majors Shell and Chevron are among the key players eyeing the Philippine LNG market.

Russia, the fourth-largest LNG exporter globally, has also joined the fray, marketing gas as an “eco-friendly” and affordable energy source that can help ASEAN leave polluting coal and diesel behind. In response to the IEA’s appeal to halt investments in new fossil fuel supply, Australia’s top oil and gas industry groups criticised the organisation for not taking into account future negative emission technologies and offsets. There was “no one size fits all” for decarbonisation, the groups said. Australia is the world’s biggest gas exporter.

“Gas is not a transition fuel; it’s a fossil fuel. By building more gas infrastructure, Asia is locking itself into outdated and carbon-intensive assets that come with vast financial risk. But the fossil fuel industry will lobby and lie for as long as it can,” said Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies, Australasia at IEEFA.

Bank-rolling gas

Until now, financial institutions have largely spurred the industry on. In 2020, banks funnelled US$28.8 billion to the 30 biggest LNG suppliers in the world, more than in any year since the Paris Agreement was signed, according to a recent report by environmental campaigners Rainforest Action Network. Some of the biggest investors include JP Morgan Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America. JP Morgan Chase alone pumped US$316 billion into LNG projects, while BNP Paribas has emerged as the world’s top funder of offshore oil and gas.

Besides multinational firms such as ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, and Total, colossal loans have been doled out to Asian oil and gas giants including China National Petroleum and China National Offshore Oil Corporations. The study found that oil and gas financing guidelines are even further behind those for coal in aligning with the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals. In terms of international public finance, gas ventures received US$16 billion on average between 2017 and 2019, four times as much as solar and wind.

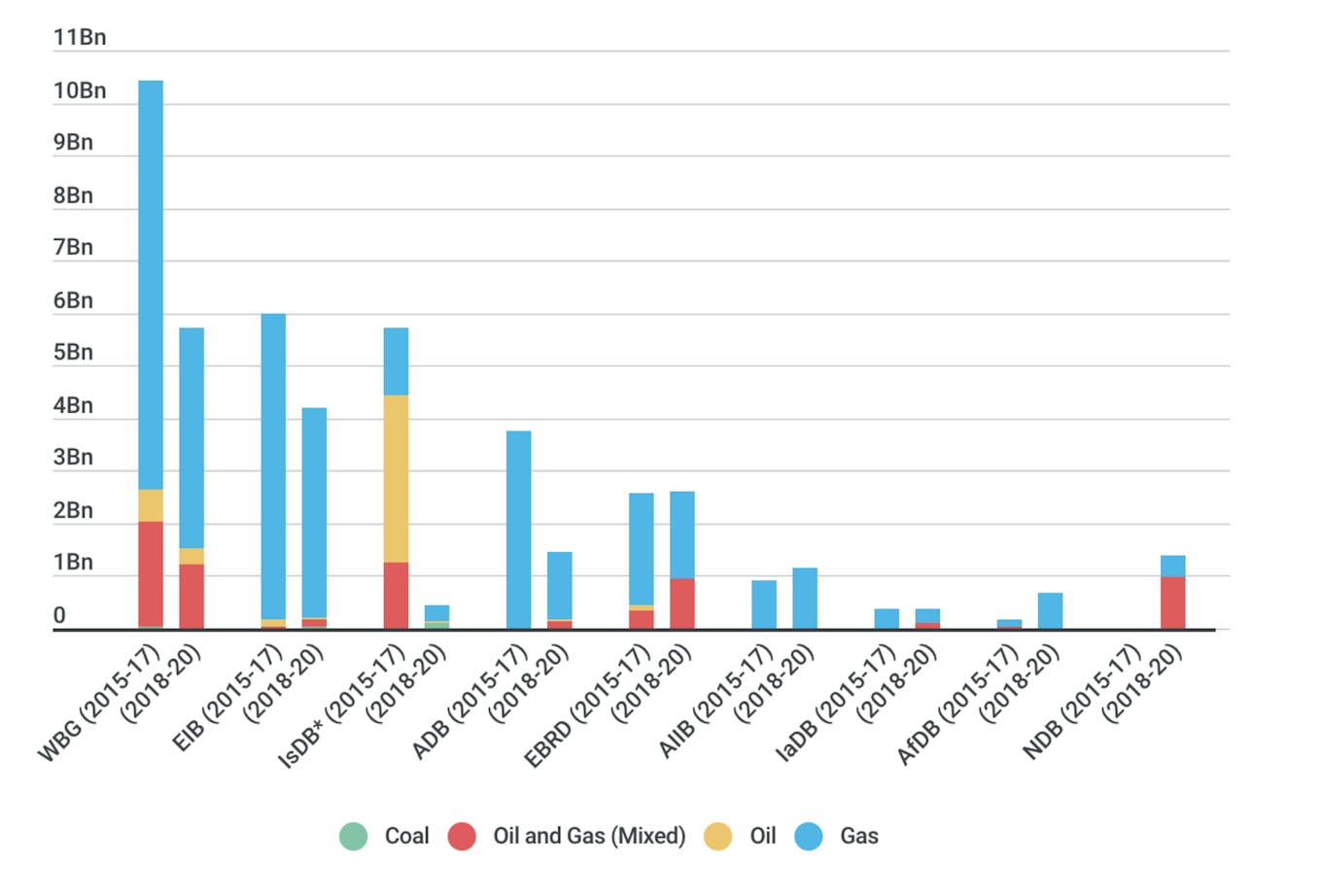

Overall multilateral development bank project finance spending on fossil fuels in 2018-2020 fell to 60 per cent of the levels in the period 2015-17. Nevertheless, MDBs are still significant sources of finance for fossil fuel projects. Image: The Big Shift Global

The data on fossil fuel financing from multilateral development banks (MDBs) paints a similar picture. According to a recent study by Big Shift Global, a campaign backed by several dozen civil society groups from around the world, the world’s nine major MDBs combined pumped over US$3 billion into fossil fuels last year. Gas received more than three quarters of this support.

While the Asian Development Bank (ADB) cut its funding for oil and gas in 2020, its technical assistance grants continue to back gas ventures around Asia. From 2018 to 2020, the bank channelled nearly US$1.5 billion into oil and gas, enabling gas-fired power development in Bangladesh as well as pipelines in India and Pakistan. It was also involved in planning an LNG terminal and power stations in Sri Lanka. The World Bank Group, which also funds major energy projects across the continent, spent by far the most on fossil fuels, with US$5.7 billion invested between 2018 and 2020.

A polluting bridging fuel

A natural gas power plant. Compared with other fossil fuels, gas emits the least amount of carbon dioxide into the air when combusted. However, substantial methane leakage during the fuel’s production and transport has increasingly come under public scrutiny in recent years. Image: Jon Sullivan, CC BY-NC 2.0

The combustion of fossil gas and the associated lifecycle emissions worry climate scientists. Carbon and other pollutants are released into the atmosphere when gas is extracted, liquefied, shipped, regasified, and used as an industrial feedstock or to generate power.

Methane leakage along the fuel’s supply chain in particular has come under scrutiny. Over its short lifetime, the powerful greenhouse gas traps so much heat that even after 100 years, the potential warming it caused is still about 25 times that of CO2. Over the first 20 years, it is 80 times more potent than CO2, making methane cuts a crucial strategy to slow down climate change.

The International Energy Agency (IEA), a Paris-based organisation and widely considered the world’s leading voice on energy transition issues, estimates that the oil and gas sector emitted 82 million tonnes of methane in 2019—about three times the CO2 equivalent that Germany released into the atmosphere that year. Despite initial industry-led initiatives, methane emissions have remained high.

In May, the agency warned that exploitation and development of new oil and gas fields as well as coal-fired power stations must stop this year, and that oil and gas consumption would need to drop by 75 per cent and 55 per cent, respectively.

“

Gas is not a transition fuel; it’s a fossil fuel. By building more gas infrastructure, Asia is locking itself into outdated and carbon-intensive assets that come with vast financial risk. But the fossil fuel industry will lobby and lie for as long as it can.

Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies, Australasia, IEEFA

While four decades of climate negotiations have almost exclusively focused on CO2, the most abundant planet-heating gas, a landmark report by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns that “strong, rapid and sustained reductions” in methane emissions will be critical to avert dangerous heating, with methane behind an estimated 30 per cent of the global temperature rise of 1.2 degrees Celsius since the pre-industrial era.

Another forthcoming IPCC report, a draft of which leaked last month, urges that achieving international climate goals will require global greenhouse gas emissions to peak in the next four years. Both coal and gas-fired power plants must close in the next decade to avoid climate breakdown, the analysis shows.

With irrevocable science, major economies are towing the line. The United States and European Union announced on 18 September a Global Methane Pledge, an initiative to reduce methane emissions by at least 30 per cent from 2020 levels by 2030 and moving towards using best available inventory methodologies to quantify methane emissions, with a particular focus on high emission sources.

Shifting tides

An activist protesting against JP Morgan Chase’s fossil fuel financing in the United States. JP Morgan has pumped $269 billion into fossil fuels expansion since the Paris Agreement, 36 per cent more than the next biggest funder of coal, oil and natural gas. Image: Banking on Climate Change 2020 report

Subdued investment in fossil fuels is leading to supply and price volatility which could derail Asia’s future gas development. A 2020 IEEFA report argued that current market trends as well as progressively tighter oil and gas lending guidelines reflected growing investor concerns over looming stranded asset risks, predicting that the financial sector’s oil and gas exits will follow a similar path to recent thermal coal exits, which more than 150 major banks announced as of last year.

Last December, the United Kingdom announced it would end taxpayer support for all fossil fuel projects overseas “as soon as possible”—albeit with “limited exceptions”—to back a transition to low-carbon energy. The following month, the European Investment Bank, the world’s largest multilateral lender, pledged to stop all funding for fossil fuels before the end of the year, with its president bluntly declaring that “gas is over”.

Even the United States, the world’s third-biggest gas seller, has pulled back from financing polluting energy ventures with its recent move to restrict the funding of fossil fuels through multilateral development banks, marking a substantial shift in policy away from promoting gas exports and infrastructure abroad. While the country left the door open for midstream and downstream gas projects necessary for energy security and where clean alternatives are “unfeasible”, the announcement is set to deal a blow to coal, oil and gas project development in the Asia Pacific, as the country is a major shareholder in both the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. The announcement came on the heels of the ADB’s pledge to fully align its energy investments with the Paris Agreement by 2025.

Meanwhile, the industry faces headwinds across Asia amid regulatory and financial uncertainties and pressure to cut emissions. In China, at least five new LNG regasification terminals and two terminal expansion projects were reportedly delayed last year partly due to financial strain plaguing private companies, leaving just two ventures on track.

“

Asia’s emerging markets are extremely price-sensitive and will find it challenging to handle persisting price volatility. Energy affordability remains a key concern in these countries because many people are still dragging themselves out of poverty.

Tim Buckley, director of energy finance studies, Australasia, IEEFA

In Vietnam, unresolved bureaucratic hurdles have left gas projects in limbo even as the sector’s questionable green credentials create uncertainty over where funding will come from. The IEEFA has cautioned that LNG suppliers and developers looking to turn the country into an essential LNG market should not expect to replicate the success renewables have seen. In December last year, only nine projects accounting for less than 20 per cent of gas power capacity proposed to authorities had been formally approved, and none of them had finalised power purchase agreements with Vietnam’s state utility.

Similar obstacles hamstring gas development in the Philippines, where the lack of clear legal frameworks risks turning projects worth nearly US$14 billion into stranded assets, another IEEFA study warned in May. In Indonesia, Wood Mackenzie has forecast tough times for new gas-fired generation ventures this year amid a slowdown in energy demand growth. And in Singapore, which sources more than 95 per cent of its electricity from fossil gas, officials are mulling new emissions standards for power generation firms.

The Covid-19 crisis has further dampened prospects for gas, as slower energy demand growth in countries like Japan, South Korea, the United States and Europe as well as green stimulus plans are expected to allow renewables to take up greater shares in the energy mix. “Until recently, some folks in the industry were saying that gas demand would grow by six per cent per year over the next 20 years. Some industry players still say that, but I just don’t believe it will happen,” said Eurasia Group’s Gloystein.

In Southeast Asia, there is also concern about it excessive reliance on imported LNG, curbing the region’s appetite for rapid expansion. Traditionally, Southeast Asia’s considerable oil and gas resources have allowed the bloc to enjoy a net energy export position, valued at more than US$10 billion annually at the start of the century. While Southeast Asia’s overall gas production is projected to edge higher over the next two decades, rapidly rising demand is set to drag down the regional gas export surplus, turning the bloc as a whole into a gas importer in the late 2020s, with implications for its energy import bill, trade balance, and energy security.

Exacerbating such fears are increasingly unpredictable gas market dynamics. An IEEFA study warned earlier this year that record-high spot LNG prices, pushed up by exceptionally cold temperatures and a collapse in drilling activity in the United States, could see many gas projects become unbankable, putting US$50 billion of ventures across Bangladesh, Pakistan and Vietnam at risk. The report pointed out that the unprecedented price hike could cause power plants to partly lie idle this year, making gas-fired electricity unaffordable. While industry advocates were quick to declare that the price rollercoaster wouldn’t last, it now looks increasingly likely to stay and could prompt Asian governments to revaluate their power development plans, bolstering the case for a pivot to renewables.

“Asia’s emerging markets are extremely price-sensitive and will find it challenging to handle persisting price volatility. Energy affordability remains a key concern in these countries because many people are still dragging themselves out of poverty,” IEEFA’s Tim Buckley told Eco-Business. “These price spikes will accelerate the industry’s extinction and boost the commercial viability of cleaner alternatives.”

Watershed moment

It is a critical time for the sector, as policies introduced now will shape the fuel’s future in Asia. Recognising the urgency, the industry has sought to show its commitment to address its climate impacts in a bid to remain relevant in a rapidly decarbonising world.

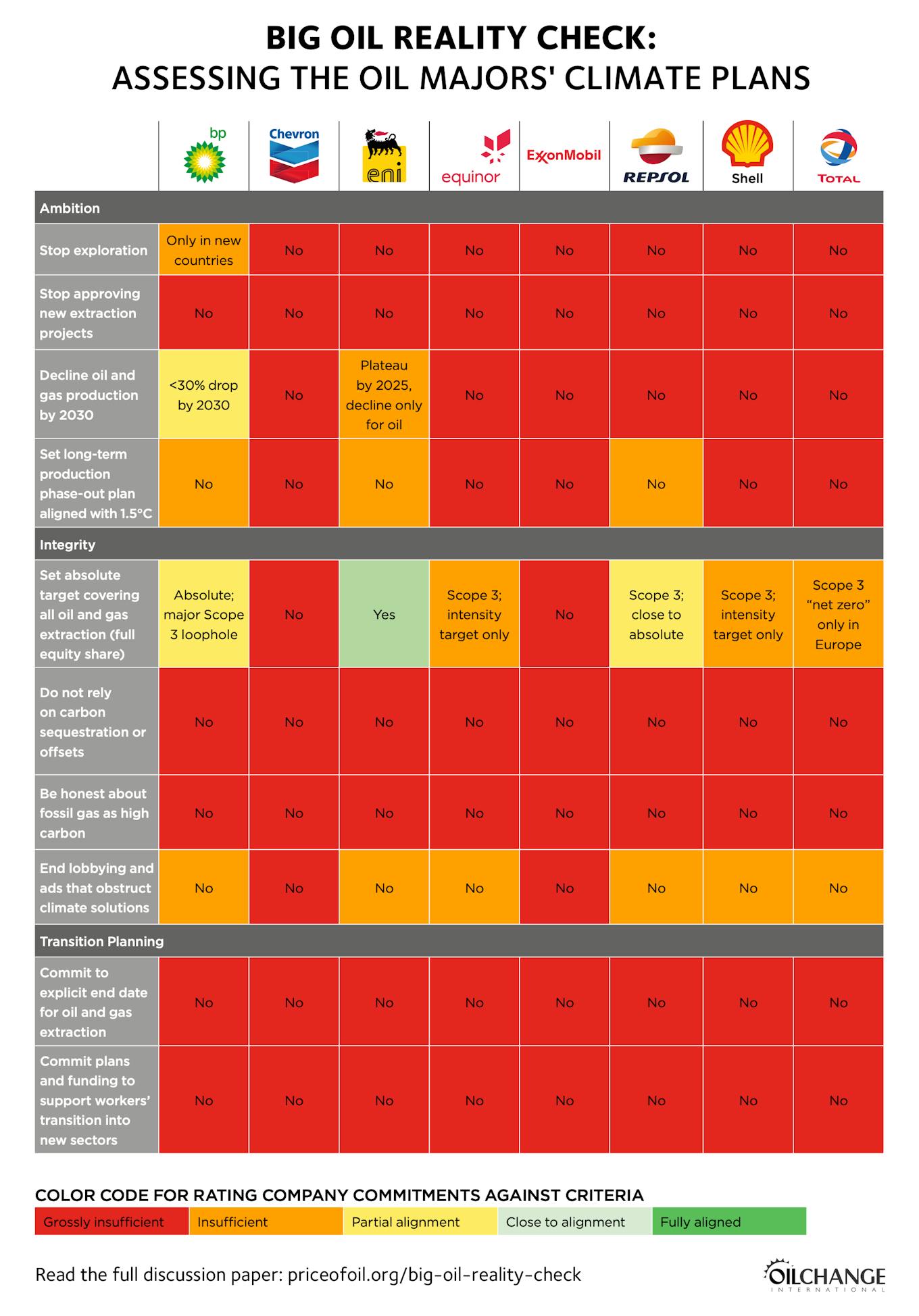

One strategy has been to set ambitious long-term targets. Yet several oil major’s net-zero emissions pledges have been shown to contain vast loopholes. A 2020 paper by Oil Change international looked at the current climate commitments of eight of the largest integrated oil and gas firms, including BP, Chevron, Eni, Equinor, ExxonMobil, Repsol, Shell, and Total. It found that none of the evaluated oil majors’ climate strategies, plans and actions comes close to being compatible with the Paris Agreement’s goal of keeping heating below 1.5 degrees Celsius. Only one oil major, BP, has committed to an absolute reduction in oil and gas extraction by 2030. However, it has excluded from that commitment around 30 per cent of the carbon pollution associated with its extraction investments.

‘Big oil reality check’, a paper by Oil Change International measures oil and gas company climate plans against ten minimum criteria, focusing on the ambition, integrity, and ability necessary to implement a just transition and achieve a 1.5°C aligned managed decline of oil and fossil gas. Image: Oil Change International, 2020.

The industry has also pinned its hopes on carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) solutions to slash emissions, despite concerns that the technology remains unproven. Environmentalists have called it a “dangerous distraction”, arguing that it will not mature in time to deliver the deep emissions cuts needed.

The recent controversy surrounding Chevron’s Gorgon project, a US$54 billion LNG plant equipped with CCUS, a facility in Western Australia, is likely to further tarnish the technology’s image. A decade ago, Chevron promised to store 100 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions, but the energy firm recently admitted it had failed to meet the Australian government’s requirement to lock away 80 per cent of emissions generated within its first five years of operation, blaming “technical challenges”.

Chevron Gorgon liquefied natural gas plant, Western Australia. Chevron admitted in July it had failed to meet Canberra’s requirements to lock away 80 per cent of emissions generated within its first five years of operation. Image: Chevron

Yet the gas sector’s technological optimism is the foundation for its foray into cleaner hydrogen, an energy carrier that is widely deemed a possible key technology in a future low-carbon world, where it could be used to power industry and transport, heat buildings, and generate electricity. Today, most hydrogen is classified as “grey” hydrogen because it is supplied through steam reforming of methane in gas, with high emissions. Industry advocates call for CCUS to be used to reduce these emissions and create a climate-friendlier alternative called “blue” hydrogen.

The gas industry is increasingly promoting carbon-neutral LNG cargoes using carbon offsets that finance renewable energy ventures or the protection and restoration of forests. But such climate mitigation measures have drawn criticism for relying on offsets rather than direct emissions cuts.

A key challenge is that offset schemes are notoriously murky because of poor monitoring and weak regulatory enforcement. Reports have emerged about funds being used to clear forests they were meant to protect, Eurasia Group said. A recent industry brief by the consultancy highlighted that offsetting all emissions would require them to be credibly measured along the LNG supply chain and then offset by an equally reliable mechanism with a transparent carbon price.

“

The idea of replacing every megawatt of coal with LNG as a solution to the world’s climate problem isn’t valid. [Asia needs] to be a bit more ambitious.

Henning Gloystein, director of global energy and natural resources, Eurasia Group

The problem is that the most credible carbon offsetting projects tend to carry the heftiest price tags, raising the cost of “green” LNG to prohibitive levels, according to the brief. To keep costs low, some LNG players do not take the full scope of emissions into account, or they buy the cheapest offsets available.

“Offsetting will probably be needed to get to net zero, but we need more credibility and far better standards than there are now,” said Gloystein of Eurasia Group. “Some of the offsetting that’s being done is appalling, while some of it is really good but so expensive that LNG prices itself out of the market.”

The first LNG marketed as carbon neutral was sold in Asia, and various Asian buyers have since signed similar deals with the likes of Shell, Japanese utility JERA, and Singapore’s Pavilion Energy. According to Eurasia Group, the region’s carbon offsetting standards are much less stringent than Europe’s, and as pressure builds on governments to help tackle climate change, appetite for presumably green LNG is likely to grow.

Clearing the way for renewables

Floating solar panels on Srinakarin lake, Thailand. If Southeast Asia does not transition to clean energy, the region could suffer annual losses of 4.5 per cent of GDP over the next 30 years.Image: Uwe Schwarzbach/Flickr

Coal currently makes up more than half of Asia’s energy supply, offering enormous opportunities for fossil gas to drive a reduction in emissions. Yet gas is the fastest-growing source of greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel burning in the world. Clean alternatives, on the other hand, are either already cheaper or expected to be within a few years, research by the International Institute for Sustainable Development, a Canadian think tank, shows.

In India and China, the cost of new utility-scale solar power has fallen to levels as low as US$20-40 per megawatt-hour (MWh), making it cheaper than coal. In Thailand and Vietnam, solar and wind are also more affordable than coal, with most Southeast Asian markets expected to follow in the coming years. In Malaysia, Cambodia, and Myanmar, solar auctions have already hit prices of around US$40 per MWh.

The gas industry has positioned itself as a partner to intermittent solar and wind power in the climate fight. Yet renewables don’t see it that way. Critics caution that gas power infrastructure built today will be around for decades, threatening to impede the shift to green energy, not least because contracts required for gas investments often involve long-term commitments to purchase and burn the fuel.

“Renewables and the gas industry are not natural partners. Renewable energy players see the sector as a competitor. For sure, coal is the preferred target of everybody, but both renewables and gas are fighting for market share of each megawatt,” said Gloystein.

The LNG industry’s plans to build small-scale gas power plants on small islands counters studies that make the case for renewables as an affordable and reliable solution for such applications. A recent IEEFA report on small-scale LNG projects in Indonesia also calls the economics of such ventures “problematic”.

Recent advances in energy storage also render gas as a backup solution obsolete, with the average price of a lithium-ion battery pack dropping 88 per cent over the past decade. Wood Mackenzie estimates that solar projects equipped with storage will become competitive with gas across Asia Pacific by 2026.

Cost of renewables from 2010 to 2020. The decade of falling costs culminated in solar PV and onshore wind continuously undercuttings the cheapest new coal option without financial support. Source: International Renewable Energy Agency. Image: Eco-Business

LNG will have its part to play as a fuel to generate power and an industrial feedstock in Asia’s growing coastal industrial sites. While green hydrogen produced from renewables could eventually replace gas’ industrial uses, it is at present too expensive for widespread use, although it has gained traction across the region.

Singapore is studying green hydrogen as a potentially critical part of its power sector strategy, and advocates are urging Vietnam to produce the fuel from the country’s rich offshore wind resources. China recently greenlighted a renewables-powered mega project for green hydrogen in Inner Mongolia that will harness 1.86 gigawatts of solar and 370 megawatts of wind, while India plans to use the energy carrier in its refineries and fertiliser plants.

Ultimately, countries will have to plan how to meet their energy needs in a way that’s economical while keeping emissions low. “If it’s renewables, that’s great. If it’s gas, cool. But don’t do it just because your friendly supplier of the last 20 years says gas is fantastic,” Gloystein said.

“The idea of replacing every megawatt of coal with LNG as a solution to the world’s climate problem isn’t valid. [Asia needs] to be a bit more ambitious,” he told Eco-Business. “If you’re replacing coal with gas, that’s better than replacing coal with coal, without a doubt. But it’s a halfway measure. We already have the technologies to go much cleaner. You’re halfway there. Why don’t you go the whole way?”

This article is part of a reporting series supported by Earth Journalism Network through its special collaborative journalism project “Available But Not Needed,” which brings together six media outlets and more than a dozen reporters across seven countries to explore how public and private investments continue to fund fossil fuel economies in Southeast Asia.