It is a little odd that a problem that kills 4.7 million Asians a year doesn’t make many headlines. Particularly since the culprit—air pollution—is more severe in Asia than anywhere in the world.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Air pollution kills more Vietnamese than motorbike accidents, more Indonesians than malnutrition, and more Filipinos than guns. In fact, Asia accounts for 60 per cent of the world’s population, but two-thirds of all air pollution deaths.

So why don’t air pollution stories excite editors much here? It is a question that puzzled delegates at the Better Air Quality (BAQ) Conference in Kuching in November.

“

We have such a politically turbulent society, with such a newsworthy president, that air pollution has a hard time breaking through the political noise.

Howie Severino, investigative journalist, the Philippines

See no evil, report no evil

The obvious reason is that air pollution is hard to see. It’s not easy reporting on something that is invisible. Until it isn’t. Singapore’s skyline, impressive though it is, is not news. Singapore’s skyline cloaked in thick haze is.

Singapore’s skyline obscured by haze caused by slash-and-burn forestry in neighbouring Indonesia in 2015. Image: Shutterstock

For this reason, air pollution in Singapore—which is regularly 80 per cent above the level considered safe by the World Health Organisation (WHO)—is only reported once a year, when smog from slash-and-burn forestry in neighbouring Indonesia sends air pollution readings through the roof. But as the last three years have been relatively haze-free, air pollution coverage has all but evaporated.

How polluted are Asia’s cities?

| Times over WHO safe level | National air pollution deaths | |

| DELHI | 14.3 | 1,795,181 |

| ISLAMABAD | 10.7 | 212,433 |

| ULAANBAATAR | 9.2 | 2,784 |

| BEIJING | 7.3 | 1,944,436 |

| DHAKA | 5.7 | 166,598 |

| HANOI | 4.8 | 60,627 |

| JAKARTA | 4.5 | 211,916 |

| COLOMBO | 3.6 | 20,474 |

| SEOUL | 2.6 | 17,832 |

| KUALA LUMPUR | 2.5 | 10,479 |

| NAYPYIDAW | 2.4 | 60,467 |

| SINGAPORE | 80% | 2,208 |

| MANILA | 70% | 122,576 |

| TOKYO | 70% | 58,287 |

| CANBERRA | 60% | 4,361 |

Sources: WHO, UN Environment, BreathLife. Air pollution metric: annual PM2.5 exposure, 2018

The scenario is similar in Malaysia, where the average annual level of PM2.5—particles 2.5 microns wide that penetrate deep into the lungs—is significantly higher in the capital, Kuala Lumpur.

“We only tend to talk about air pollution when it’s really bad,” said Kamarul Bahrin Haron, deputy editor in chief at Astro Awani, Malaysia’s satellite TV giant, on a panel discussion on media and air quality at BAQ.

Data on air pollution media coverage by public health non-government organisation (NGO) Vital Strategies backs this up. According to a trawl of air pollution-related press articles and social media content in 11 countries in South and Southeast Asia over the last four years, there was a spike in coverage in 2015, the year of the Southeast Asia haze crisis and the announcement of the odd-even license number plate rule in Delhi, which the previous year WHO had declared the world’s most polluted city.

In 2016 and 2017, air pollution coverage flatlined. But it re-emerged this year, when athletes collapsed at the Asian Games as a result of Jakarta’s air and smoggy skies returned to Beijing.

In a region with a medley of social and environmental issues, a slow-burning, invisible menace fades into the background. Maintaining media interest in air pollution is difficult in Indonesia, where environmental problems range from deforestation to illegal mining, says Ichwan Susanto, a journalist for national daily Kompas.

The story is similar in the Philippines, where ageing Jeepneys choke the congested capital Manila and air pollution has become “normalised,” says Howie Severino, an investigative journalist for GMA Network, a tv channel.

“We have such a politically turbulent society, with such a newsworthy president, that air pollution has a hard time breaking through the political noise,” says Severino, who hosts the documentary show i-Witness.

So the documentary maker, a keen cyclist and clean air advocate, looks for stories that make air pollution visible. His short documentary Black Manila, about people living on a charcoal-making complex, doesn’t need subtitles. The images speak for themselves.

But without Dickensian characters picking through blackened landscapes, air pollution doesn’t leap off the page. Even in China, the world’s air pollution champion until dethroned by India four years ago, coverage has started to wane as air quality improves, says Tao Wang, an environment reporter for Southern Weekly newspaper.

Data drift

A lack of reliable data, or any data at all, is a reporting obstacle, as is knowing how to interpret it, journalists noted during the panel discussion in Kuching. “Please don’t ask the media where the reporting [on air quality] is, if you guys [the air quality sector] are not helping us get the data,” said Haron of Astro.

Journalists often find the data confusing. There are so many types of pollutants—PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, ozone. Which tells the better story? And air quality standards vary a lot by country, making regional comparisons difficult. What is considered low pollution in Mongolia is considered very unhealthy in Singapore and Malaysia.

For the last 4 years, the media has stated and restated the problem. But the quality of air in India is getting worse, and the media hasn’t started talking about solutions.

Amitabh Sinha, resident editor, The Indian Express

Haron gripes that data pitched to journalists is often impenetrably academic. He suggests that data be presented in “sexier” ways, using graphics, colour and animation to make it more interesting.

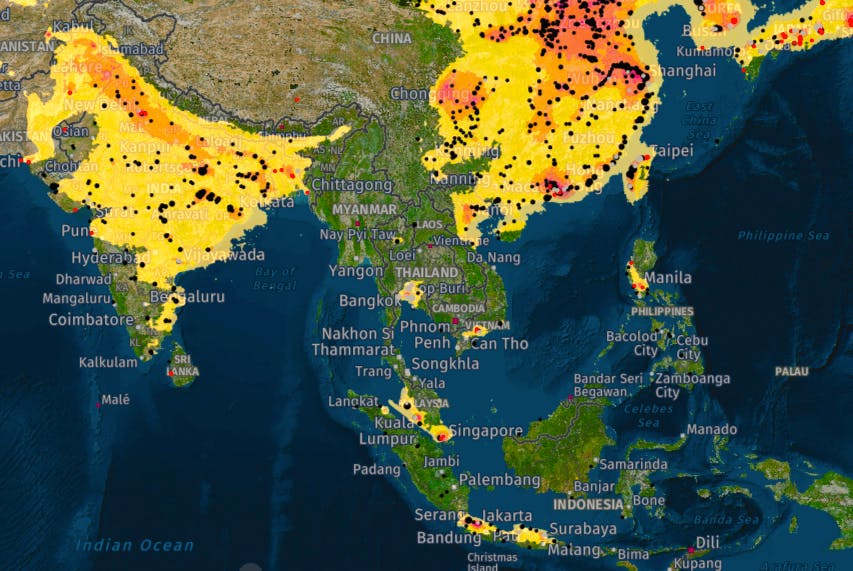

Maps are one way to do this. Last month, Greenpeace launched the most detailed maps yet of NO2 pollution worldwide, using data from World Resources Institute and CoalSwarm. The interactive map, which uses smog-tracking satellites, shows the NO2 hotspots around the region, as well as the location of coal, oil and gas plants.

Nitrogen dioxide pollution hotspots around Asia. Black dots denote coal-fired power stations, red dots denote oil plants and grey dots denote gas facilities. Image/sources: Energydesk, World Resources Institute, CoalSwarm

Restating the problem, ignoring the causes

One country where air pollution has not been undercovered is India. When Delhi eclipsed Beijing as the world’s most polluted city in 2014, an unprecedented level of air pollution coverage followed, says the resident editor of The Indian Express, Amitabh Sinha, whose newspaper ran frontpage stories for 10 days straight on the capital’s worsening air.

A Sri Lankan bowler is sick during a cricket match against India in Delhi. Image: Altaf Qadri/AP

The story of Delhi’s air began to feed on itself, Sinha recalls. Embassies issued travel alerts, and employees of foreign embassies fretted about locating their families in the capital. New life was breathed into the bad air narrative when Sri Lankan cricketers vomited during a test match in Delhi a year ago, when air quality reached 12 times the WHO limit.

But India’s coverage of air pollution, though extensive, has been dominated by stories that report the problem rather than how to solve it, says Sinha. “For the last 4 years, we have stated and restated the problem. But the fact is that the quality of air in India is getting worse, and the media hasn’t been talking about solutions,” says Sinha.

Media noise, combined with pressure from civic society groups, has led to measures to tackle air pollution, such the National Clean Air Programme announced in April, which critics say was a long time in coming. But the press could have done more to probe the implementaton of the programme, particularly polluting industries’ “very, very poor” emissions compliance record, says Sinha.

Why aren’t journalists writing about pollution solutions?

The media is too often seduced by the fear-based “if it bleeds it leads” approach to reporting, but that can make people numb to the issue, or bored by it, says Severino.

“Solutions are being tried out, but they just don’t make the news,” he says. “The media has a role to find stories of hope, so they can inspire people and make them feel less helpless.”

But stories about installing air filtration units don’t make for scintillating copy, while gimmicky solutions such as smog-inhaling t-shirts and air-cleaning paint may interest editors but not public health experts.

“

Vehicles are convenient for governments [to blame for air pollution], because they make the middle class a part of the problem.

Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst, global air pollution unit, Greenpeace

Meanwhile, effective solutions such as a shift away from polluting coal-fired power plants to cleaner energy sources go relatively unreported. Vital Strategies’ trawl of the region’s air pollution coverage found a disconnect between what the media perceives to be the biggest causes of air pollution, and how to tackle the problem.

The study of 14,000 Asian press articles found that vehicular emissions were perceived to be by far the biggest cause of air pollution, while power plants barely featured. But when the study trawled for perceived solutions, the need for energy efficient power generation came out on top.

The study also showed that when reporting on solutions, articles tended to present government policies on pollution, and not challenge the authorities on the effectiveness of these policies.

“Vehicles are convenient for governments [to blame for air pollution], because they make the middle class a part of the problem,” says Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst, global air pollution unit, Greenpeace.

“Vehicle bias” is particularly pronounced in India, where studies have shown that traffic contributes in a very small way to overall PM2.5 levels, says Myllyvirta.

Traffic is the biggest contributor to air pollution in South and Southeast Asia, accounting for more than a third of emissions that region, according to a 2015 study by European Commission. But burning coal is the single biggest cause of air pollution-related deaths in China, and the most worrying future source of air pollution in India, it was noted by Robert O’Keefe, chairman of Clean Air Asia, at BAQ.

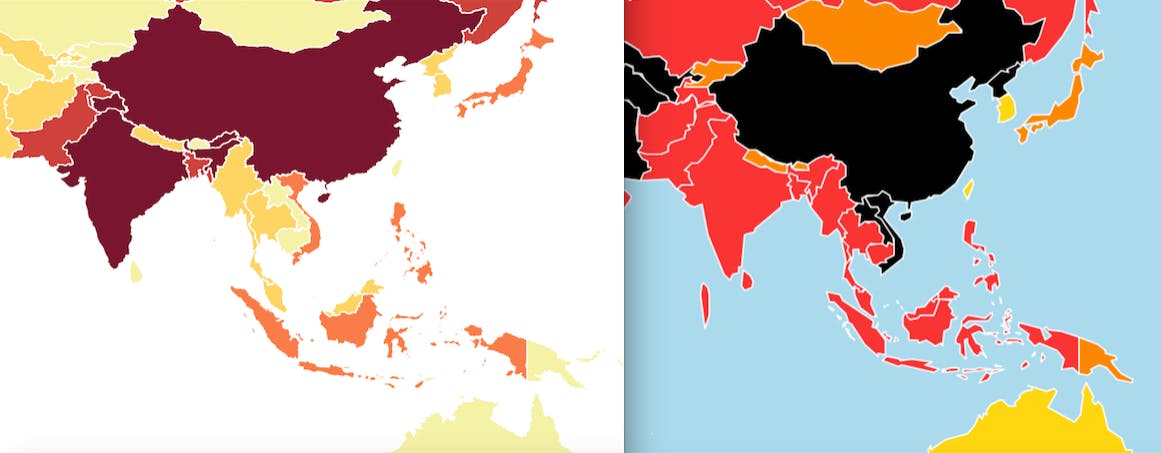

Reporting on a fuel that is so central to economic development—Asia is the biggest and fastest growing region in the world for coal power—can be a sensitive subject, says one source at a civic society group in Vietnam. As the maps below indicate, countries that suffer from bad pollution also happen to have the least free media to report on the problem.

Map on the left shows average annual population weighted PM2.5 levels, with darker shades indicating more polluted countries. Map on the right shows press freedom levels, with darker shades indicating countries with a less free press, Sources: Reporters without borders, State of Global Air

In Indonesia, which for Southeast Asia has a relatively free press (ranking 124th in the Reporters without Borders press freedom rankings, above the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam and China), politicians downplay the polluting menace of coal. Around the time of the Asian Games, the director of air pollution for Indonesia’s environment ministry, Dasrul Chaniago, denied that power plants in Banten province could pollute air in Jakarta, which was hosting the Games 100km away.

“Why would smoke from coal-fired power plants travel all the way to Jakarta? Does it want to go to the shopping malls here?” Chaniago told reporters. “Are you sure smoke from power plants in Banten can be carried by the wind to Jakarta? You’re given the ability to think by God. We have logic. We’re not animals.”

Myllyvirta, who was behind a study of air pollution in Jakarta that has pushed the issue up the political agenda, notes that the city is a special case—no other capital has so many coal-fired power stations so nearby.

“Jakarta has Southeast Asia’s most polluting power plant, by far, less than 100km from the city. For anyone who understands how pollution travels in the atmosphere that’s shockingly close. But for most journalists and laypeople in Jakarta that plant might as well be on another planet.”

A bigger problem than underestimating the polluting punch of power plants is for journalists to fixate on a single source when air pollution is usually a cocktail of many, says Myllyvirta.

“If you are serious about improving air quality substantially, you have to look at all the main sources—especially in emerging Asia where if you focus on one source, emissions from the others will increase and offset your efforts,” he says.

The invisible killer

Vital Strategies’ media study also found that journalists in Asia are not accurately reporting the impact of air pollution on health. The majority of articles made no mention of its health effects, and those that did reported non-chronic health impacts such as breathing difficulties, dry throat and itchy eyes. Just 5 per cent reported chronic effects such as lung cancer and heart disease.

“This is likely due to a lack of awareness of the longer term health impacts of air pollution, and the need to make the story ‘current’ by mentioning health impacts that people are experiencing at that point in time,” comments Aanchal Mehta, Vital Strategies’ communications lead, environmental health.

So what will it take for Asia’s media to cover air pollution more? It could be a better understanding of which stories have the most bite. Air pollution stories that mentioned children’s health got by far the most traction, the research found. Children’s health is a strong hook and a way to get the readers’ attention, Mehta noted.

Myllyvirta says that better data is needed to give journalists a clearer picture of air pollution, pointing to a “research gap” on pollution sources in many Asian cities. Even more important is for that research to be communicated in a way that reaches the public, he says.

“It will take a combination of committed, diligent journalists, campaigners and analysts who boost each other’s efforts.”