A dearth of “bankable” sustainability projects could be applying the brakes to Indonesia’s energy transition, experts said at a conference in Jakarta this week.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Speaking at the inaugural Unlocking capital for sustainability Indonesia event on Thursday, Jiro Tominaga, Indonesian country director for the Asian Development Bank said that while there was growing interest from the private sector in funding clean energy projects in Indonesia, investors were shying away from the risk profile of climate projects they are not confident would generate a return.

“A lot of interesting investors are looking at opportunities to invest [in renewable energy projects]. The challenge in the short and medium term is how to develop a system that channels financing into sustainability projects. That’s an area we need to work very hard on – the risk and return profile,” he said.

While there is no shortage of investor interest in climate ventures, issues such as an inability to scale remote off-grid clean energy projects and generate a return have impacted their financial viability. “One of the big challenges is the lack of bankable [renewables] projects,” said Tominaga, referring to the financial viability of a project, and whether or not a bank will support it.

While renewables projects are proving to be difficult investment opportunities, carbon-locking conservation projects are also problematic. Lucita Jasmin, director of sustainability and external affairs for paper and pulp company Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) said that nature-based solutions projects run by non-profits or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are rarely bankable.

“NGOs do not know how to make their initiatives bankable, because historically they have been donor-funded,” said Jasmin, who added that APRIL is working with NGOs to build the financial viability of nature-based solutions projects in Indonesia.

Jasmin stressed the need to build capacity among conservation groups by providing funding, technical and operational support, to ensure that conservation becomes a sustainable livelihood source for communities over the long term.

One of the big challenges is the lack of bankable projects that address the climate issue.

Jiro Tominaga, Indonesia country director, Asian Development Bank

Tominaga noted that, according to ADB calculations, Southeast Asia needs $210 billion annually to fund the energy transition through to 2030, and the regional bloc’s largest economy will need in the region of US$20 billion a year.

As of 2020, the Indonesian government could only meet 34 per cent of the total investment needed to achieve its national determined contributions to the Paris climate accord. The bulk of the capital needed to fill Indonesia’s climate finance gap must come from the private sector, Tominaga said.

“How the public sector can de-risk sustainability projects and activities is a key challenge we’re facing,” he said.

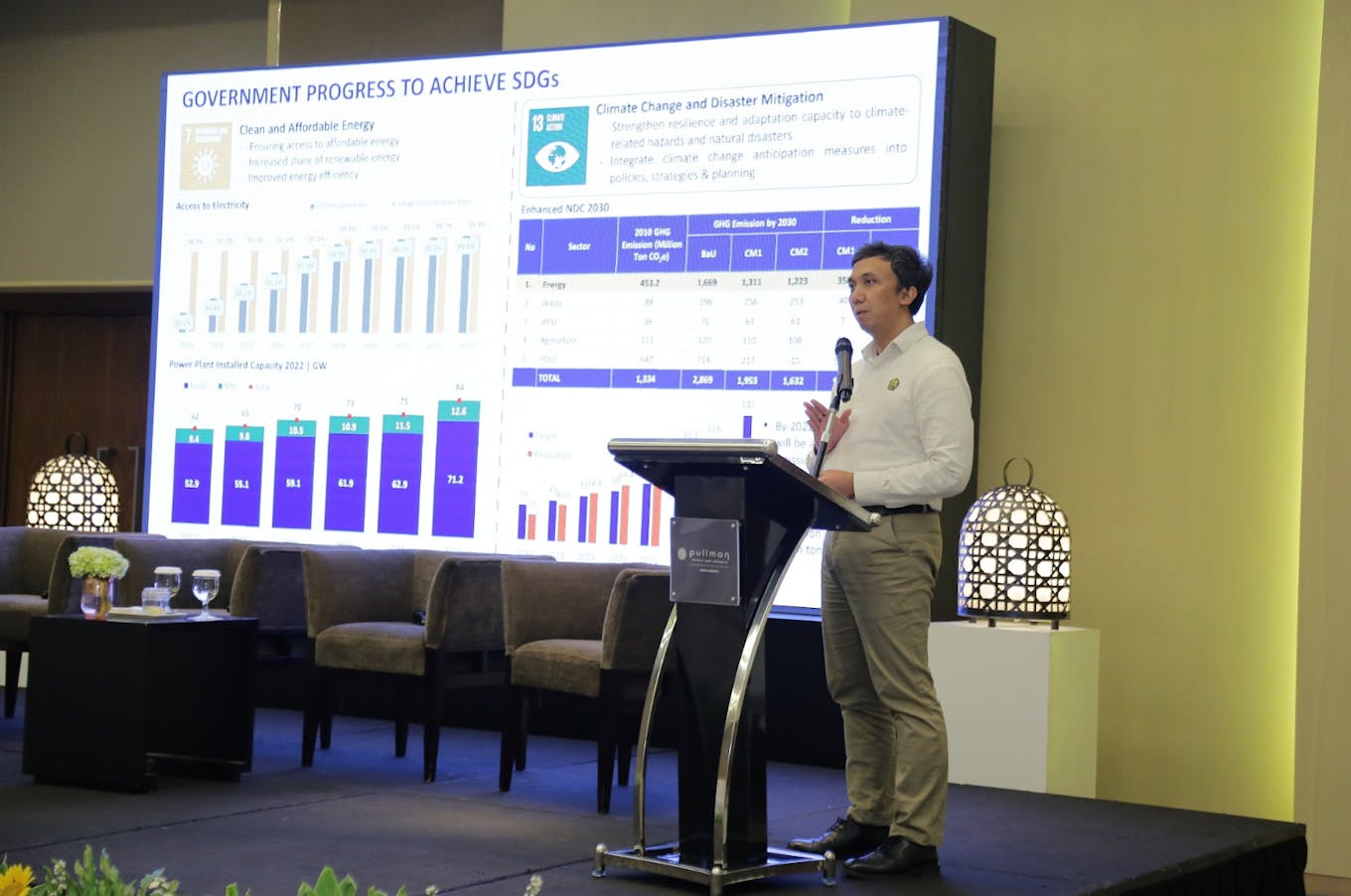

Dr Gigih Udi Atmo, director for energy conservation, Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, addressing the inaugural Unlocking Capital for Sustainability Indonesia event in Jakarta on Thursday 31 August. Image: Eco-Business

Retiring coal, upgrading the grid

With better access to capital for clean energy projects, Indonesia will in theory be able to reduce its reliance on climate-wrecking coal, which makes up more than half of the country’s energy supply and a large chunk of the country’s emissions profile.

The Indonesian government last year set a new target to cut emissions by 31.89 per cent by 2030 as it progresses towards a national net-zero emissions by 2060 goal. The new target was still rated as “critically insufficient” by global climate research consortium Climate Action Tracker.

Indonesia has pledged to cut emissions by 43.2 per cent by 2030 – if it receives sufficient international support, much of which will come in the form of financing to retire coal-fired power plants early.

“We can do early [coal] retirement, but that is subject to low cost financing, grants and concessional loans [from the international community],” said Dr Gigih Udi Atmo director of energy conservation at Indonesia’s Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources.

“There is a need to make the transition cheaper to avoid continuously operating [coal] assets,” he said at the event at the Pullman Hotel in Jakarta.

Gigih’s comments come the week after a deal between Indonesia and a group of wealth nations to wean the country off coal – known as the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) – was shelved after it emerged that Indonesia’s newly built captive coal plants were not factored into the conditions for Indonesia to access US$20 billion in climate finance.

Retiring Indonesia’s fleet of 118 coal-fired power stations has been estimated to cost US$37 billion, far less than what the nation spends on subsidising coal, which amounts up to $10 billion in a single year.

Indonesia needs to cap annual carbon emissions from the power sector at 290 million tonnes to access the US$20 billion in JETP funding, and much will depend on the viability of the country’s plan to decarbonise power generation.

However, a “national priority” is granting electricity access to the people still living without electricity – 99 per cent of Indonesians have electricity access – and adding emissions-reducing renewables to the grid posed energy security problems, cautioned Gigih.

Indonesia’s rickety electricity grid, even the more mature Java-Bali network, faces problems absorbing intermittent energy sources such as wind and solar. A “modern and integrated supergrid” is needed to deliver clean energy all across the archipelago of 17,000 islands, which will require more than US$1 billion a year in funding, Gigih said.

“We need to provide clean energy access to our people. We have an ambition to increase the renewables ratio to 23 per cent of the energy mix by 2025, and even that is still very challenging to achieve,” he said, noting that renewables accounted for just 12.3 per cent of the energy mix in 2022.

The government plans to increase the efficiency of its electricity supply so that it can reduce the overall demand for energy as well as add clean energy to the grid. A national target to reduce energy intensity by 1.8 per cent a year could mean Indonesia uses 40 per cent less energy, Gigih said.

The biggest obstacle for Indonesia in achieving its net-zero ambition is common to other fast-growing emerging economies in Southeast Asia, said Tominaga of the ADB. “Indonesia’s net-zero roadmap is highly complex. We want to decarbonise a country with a dynamic economy and at the same time give electricity access to everyone.”

“The challenge is how to de-couple the trade-off between economic growth and decarbonisation,” he said.

This story has been edited to reflect additional views shared during the panel discussion.