Dwindling gas reserves and the absence of new finds have spurred the Philippines’ shift towards importing liquified natural gas (LNG) with foreign and local investors funnelling billions into infrastructure.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The infrastructure boom amounts to US$13.6 billion worth of planned import terminals, power plants, ports, regasification facilities, and pipelines, according to a report by global think-tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) published on 5 May.

The Southeast Asian nation, which has signalled a transition from coal-fired power, ramped up the development of infrastructure to support the import of LNG to augment the declining reserves of the Malampaya gas field, the country’s only domestic source of energy. “The race to develop LNG facilities in the Philippines has gone from a marathon to a sprint,” the report says.

Natural gas, which accounts for over 21 per cent of the Philippines’s power generation, has been touted as a cleaner-burning fuel because it releases up to 60 per cent less carbon dioxide than coal.

Natural gas is usually transported through a pipeline, but if the deposit is large and the market is overseas, the gas may be liquefied for ease of shipping and moved through specialised tankers. Imported LNG is then regasified or reverted to its former state in the country of destination.

“

The Philippines is undergoing a rapid shift in the legal and commercial landscape, making returns on natural gas assets over the long-term highly uncertain.

Sam Reynolds, energy analyst, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis

But regulatory red-tape and an exposure to financial losses risks preventing LNG-to-power projects from coming online, the report says.

The Philippines currently lacks the “clear legal and regulatory frameworks”, with no laws specific to the natural gas industry, though legislation has been under discussion by policymakers since 2018.

Moreover, since the country’s landmark 2001 Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA) which banned government involvement in power plant contracting, there are no government-backed power purchasing agreements (PPAs) or guarantees, which could leave investors highly exposed to market risks, as they have no guarantee of a sure buyer of their electricity, according to the report.

Projects could run the risk of turning into “stranded assets”, where there is not enough cash flow to cover the debt, leading to bankruptcy for the investor.

“The natural gas industry is characterised by low profit margins and long-term payback periods for high-cost infrastructure. However, the Philippines is undergoing a rapid shift in the legal and commercial landscape, making returns on natural gas assets over the long-term highly uncertain,” Reynolds, IEEFA’s energy analyst who authored the report, told Eco-Business.

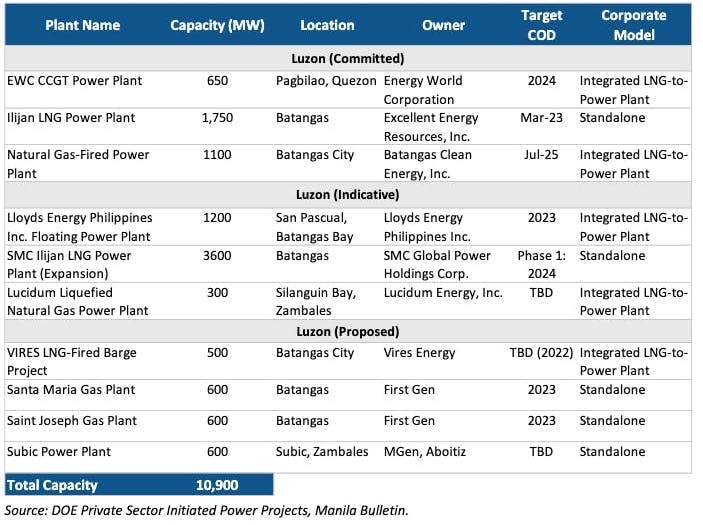

Philippines natural-gas fired power plant pipeline (as of 31 Dec 2020). The IEEFA conservatively estimates the value of LNG import infrastructure to be US$1.25 billion per GW. Image: IEEFA

Assets at risk

There are currently ten power projects in the country with nearly 11 gigawatts (GW) of generation capacity at various permitting stages, many of which are integrated with regasification facilities and storage.

The 650 megawatt (MW) Pagbilao LNG facility in Quezon province, owned by Australia-based Energy World Corporation (EWC) began development in 2009 and has suffered from multiple delays, mostly from regulatory obstacles, according to the report. Initially expected to be online in 2011, it is now slated for completion by 2024.

In 2017, EWC started to make arrangements to connect the power plant to the main Luzon grid to be constructed by the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP). But, funding requirements and transmission arrangements with multiple agencies—including the department of energy, NGCP, the National Transmission Corp and the Grid Management Committee—have caused delays to interconnection.

Failure to complete the grid connection has prevented EWC from drawing down a US$150 million loan facility from local banks which required it for the loan, according to the study.

“As a result of repeated delays, EWC has lost money and investor confidence. EWC’s stock price, listed on the Australian Stock Exchange, has plummeted from over 40 cents per share in July 2017 to below 9 cents in January 2021, while the nearly completed assets in Pagbilao have become liabilities, incurring maintenance costs without generating revenues,” the report says.

A lack of government-backed PPA’s could also scupper plans by Filipino-owned energy firm First Gen Corp and Tokyo Gas Co Ltd. The joint venture plans to build an LNG terminal in Batangas province to supply four existing gas-fired power plants, also owned by First Gen and is expected online in the fourth quarter of 2022.

Given the company’s ownership of almost the entire existing natural gas anchor market, the project is considered one of the most advanced in the country, but if it is unable to earn a PPA, they have to sell power into the spot market on a merchant basis, said Reynolds.

“But in doing so, they will face significant market risks as more low-cost renewables come online and reduce the utilisation rates of gas-fired power plants,” said Reynolds. “Idle capacity can result in the asset becoming stranded, meaning that it earns a smaller economic return than that envisaged at the outset of the project.”

Legacy of abandoned projects foreshadows progress

The cancellation of state-run Philippines National Oil Company (PNOC)’s LNG import facility casts further doubt about how the fossil fuel will fit into the local power sector, according to the research.

PNOC was supposed to have started the country’s first LNG import facility in 2018. It signed non-exclusive agreements with numerous international project developers, but they have repeatedly been bogged down by legal requirements, including a condition in the law that government-owned corporations had to seek approval from lawmakers before it could engage in big projects like an LNG terminal.

Instead of spearheading its own LNG project, PNOC decided to partner with Phoenix Petroleum, owned by Filipino business tycoon Dennis Uy, and China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) to develop the US$2 billion Tanglawan LNG Hub in 2018.

The project was eventually scrapped three years later, after Phoenix parent Udenna Corp instead acquired a 45 per cent stake in the Malampaya natural gas consortium and CNOOC reportedly ceased correspondence with the other joint venture partners.

Even in the early 2000s, local energy firm GN Power was set to construct a 1,200MW power plant fuelled by imported gas. Although the project had solid power offtake agreements, an engineering, procurement, and construction contractor, and an approved construction site, the plan was thrown out due to EPIRA reforms.

“All of this goes to show how uncertainty in legal regimes can delay timelines for LNG import developments,” Reynolds said. “The possibility of new legal developments and rule changes makes the whole investment environment uncertain, which is incompatible with an industry that requires long-term guaranteed revenues.”