From disappearing fish species to an exceptionally severe dry season, there is now clear indication that excessive damming is taking a toll on the Mekong. These impacts on the transboundary river in Southeast Asia are likely to intensify in the years to come as the pace of hydropower development along its mainstream picks up.

Increasingly, hydropower dams are becoming notorious for their adverse effects on a river’s biodiverse ecosystems and their potential to decimate the livelihoods of local riverine communities – women are disproportionately impacted by disruptions to water and food sources in rural settings where traditional roles persist.

Yet developers pursuing new projects along the Mekong are supported by easy-to-access loans. It is particularly so when the lack of disclosure requirements and long-term funding arrangements protect them from extensive scrutiny.

Large business consortiums have also been citing Southeast Asia’s growing demand for alternative energy – with most still regarding hydropower as a clean and renewable source – as the main reason to harness the power of the river basin.

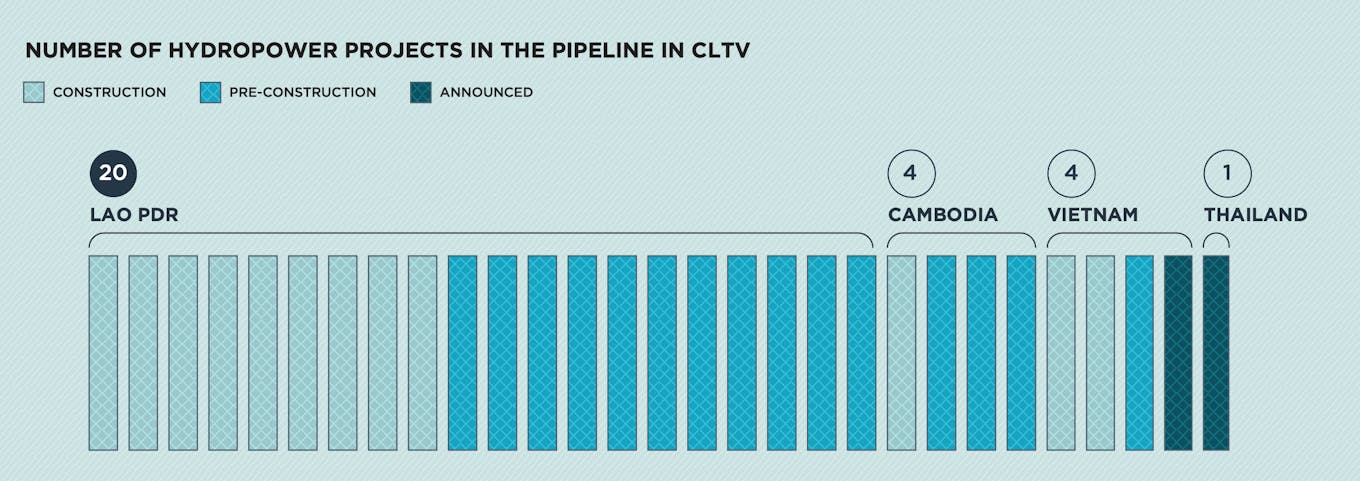

Hydropower projects operating in the Mekong countries, consisting of Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam, are seeing rapid expansion. In May 2023, there were 97 projects with a total capacity of 28,479 megawatts (MW), according to statistics from United States-based Global Energy Monitor. At least 29 new projects have already been announced or are in their construction phase, potentially driving total capacity to increase.

Now, sustainable finance watchdogs and environmental advocates are raising the alarm that the impacts on the Mekong, once free-flowing, could become irreversible if financing continues to be justified under the ambit of pushing for a clean energy transition in the region.

Laos and Cambodia account for more than three quarters of the planned hydropower capacity expansion in the region. Image: Fair Finance Asia

Some are calling on financial institutions (FIs) in the region to adopt more sustainable banking policies and practices and to fully leverage their influence to stop the tide of over-investment in dams, while others say an important first step would be greater disclosures from these banks. Civil society organisations (CSOs) like International Rivers which works with dam-affected communities call hydropower projects “destructive” and believe these unsustainable ventures should not be considered for investment.

For example, approximately four kilometres upstream of the confluence of the Nam Ou and Mekong rivers, and about 25 kilometres upstream of Luang Prabang town, a popular tourist destination and UNESCO World Heritage Site in Laos, construction of the 1,460-megawatt Luang Prabang dam on the Lower Mekong mainstream has gone ahead.

CSOs closely tracking where the Thai-driven project is getting its financial support from say that most banks have not been willing to confirm if they are involved, with the exception of Siam Commercial Bank (SCB) which made a disclosure in August this year, as it was obliged to report on project finance transactions under the Equator Principles it signed on to.

According to the Principles, lending to the Luang Prabang hydropower project, classified under a category of projects with potentially significant adverse environmental and social risks, or impacts that could be diverse, irreversible or unprecedented, would have to be disclosed. No other FI in Thailand is a signatory to the global industry benchmark for assessing environmental and social risks in project-related finance.

Construction of a dam in Luang Prabang, Laos. Construction work on the Luang Prabang dam has been ongoing for a year. Image: International Rivers

Murky world of hydropower financing

Sarinee Achavanuntakul, head of research for Fair Finance Thailand (FFT), a coalition of civic society organisations (CSOs) monitoring the impacts of Thai banks’ lending activities, tells Eco-Business that it is not uncommon that CSOs are kept in the dark when it comes to the financing of hydropower projects. FFT has reached out to major Thai banks, only to be given the silent treatment. An open letter to SCB, for example, in which the coalition requested for the bank to address questions on gaps in its project financing decision, including a neglect of salient human rights risks, has seen no official response so far.

Sarinee Achavanuntakul, head of research for Fair Finance Thailand, says civil society organisations are being kept in the dark on how the Luang Prabang dam is funded. Image: Sarinee Achavanuntakul

“Right now, we are in a dilemma. We would like to see what further advocacy we can do but the construction [of the Luang Prabang dam] has started and is proceeding at a very rapid pace,” she said. Other than SCB, no banks have come forward to confirm that they are financing the project, nor is there much public information on it, she added.

“What is interesting is that it is an indicator that whoever is financing the dam is aware of how controversial the projects are and want to avoid scrutiny.”

First proposed in 2019, the Luang Prabang hydropower project and its impact on the Mekong have been under the media spotlight, especially as there are fears that the dam’s close proximity to the town of Luang Prabang could cost it its UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

The joint Lao-Thai venture is the second dam to be built in the area after the completed Xayaburi dam, and it could transform the historic riverside town into a lakeside one, according to preliminary scientific assessments, causing it to lose its “outstanding universal value”, a former executive from the UNESCO team told media outlets early this year. Last month, UNESCO recommended that Laos invite a monitoring mission to Luang Prabang for assessment to be conducted first-hand.

An analysis that FFT published in December 2022 highlighted key environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks associated with the Luang Prabang dam including concerns that the developer has not adequately addressed the project’s transboundary environmental impacts, such as on fisheries and aquatic ecology, as well as resettlement plans that would put affected communities at risk of human rights abuses. In its latest letter to SCB after the bank disclosed that it was involved in financing the project, FFT questioned if the Thailand-headquartered bank’s resettlement action plan and environmental and social monitoring plans made available on its website in English, were communicated to locals adequately and in a culturally appropriate manner, so that all stakeholders understood any risks involved.

The Equator Principles’ secretariat, in response to a previous FFT’s complaint when SCB had not met its disclosure obligations, said that the office “does not review or opine on” the implementation of the principles by individual banks.

Equator Principles’s position is that each financial institution is individually responsible for its own internal procedures to achieve and demonstrate compliance with the principles, to adhere to the reporting requirements set out under its signatory rules, and for related communications with stakeholders.

According to FFT’s 2022 report, a review of responsible lending policies of major project finance lenders in Thailand indicated that most banks do not explicitly mention these ESG risks from large-scale hydropower projects nor outline clear screening criteria for its lending decisions. This is despite most of the major FIs in Thailand signing on to a set of responsible lending guidelines initiated by the Thai Bankers’ Association in 2019.

Sarinee, who led the report’s research work, said: “Today, many problems mentioned in the report are still there. They have not gone away. The only difference is that the project has gone ahead, as the power purchase agreement (PPA) has been signed in 2022.”

PPAs are long-term contracts that are often used as a starting point in the procurement of a hydropower plant, as they indicate that there are buyers that will offtake the energy produced.

Sarinee believes that responsible lending guidelines can “open doors” for non-governmental organisations like FFT “With this guidance, banks are more willing to engage with other stakeholders,” she said, though adding that the Luang Prabang project demonstrates that the guidelines have their limits. “Banks are not even responding to our queries.”

“

[Other than SCB which has made a disclosure], no banks have come forward to confirm that they are financing the project, nor is there public information on it…What is interesting is that it is an indicator that whoever is financing the dam is aware of how controversial the projects are and want to avoid scrutiny.

Sarinee Achavanuntakul, head of research, Fair Finance Thailand

FFT’s visit to the resettlement site last year found that local riverine communities that had to be resettled were concerned about the lack of information on resettlement plans and compensation amount. For example, through its direct engagement with affected communities, FFT found that one of the villages had been relocated to the top of a mountain with basic houses being provided, but the relocation meant that the fishermen had to adapt to new lives and depend on farming for their livelihoods.

The Luang Prabang dam is also built within the view of Pak Ou cave, a popular side trip for tourists visiting Luang Prabang. There are worries that the historic site, dating back thousands of years and packed with over 4,000 Buddha images, might suffer from damage from ecological impacts.

Sarinee said the cumulative impacts of the series of massive hydropower dams built in quick succession are concerning. Other than the Luang Prabang dam, the state-owned Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) has signed long-term PPAs with two other new dam projects on the Lower Mekong mainstream, including the Pak Lay and the Pak Beng hydropower projects. As of February 2024, 12 dams are operating on the Upper Mekong mainstream.

“Even if Luang Prabang is the first dam to be built along the Mekong, we would have concerns,” said Sarinee. “The scary thing is it is not the first dam. There are already over 10 dams, and many more to come. The effects will get worse.”

A woman community activist from Cambodia living along the Mekong River basin. Through the Mekong Water Governance programme, global organisation Oxfam works with communities across borders who are affected by large-scale water projects, including hydropower projects. Image: Oxfam Mekong Regional Water Governance

Lack of alignment with global due diligence standards

Beyond disclosure, there are also calls for banks and investors financing hydropower projects to apply environmental and social safeguards, aligned with international standards, in the construction and operation of the hydropower plants.

In its latest report “Enhancing sustainable finance in Mekong hydropower”, Fair Finance Asia (FFA), of which FFT is part of, conducted a policy assessment of key FIs in the Mekong subregion, including Thai FIs such as Bangkok Bank, Krung Thai Bank and SCB, based on the value of their loans to customers and the proportions of outstanding loans in the utilities and services industry, deemed most closely related to hydropower. It found that the public policies of the FIs assessed do not address actual and potential adverse environmental and social impacts when financing hydropower projects.

FFA is a regional network of over 90 Asian CSOs committed to ensuring that the funding decisions of FIs respect the social and environmental well-being of local communities.

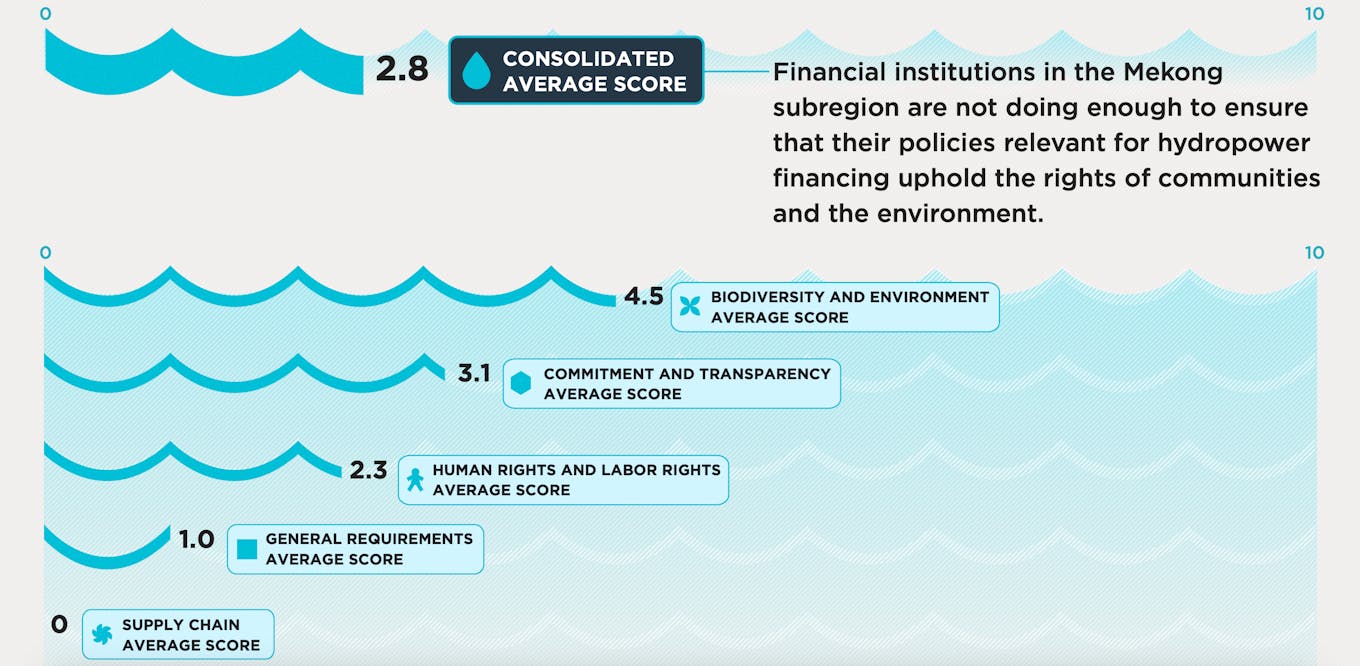

This graph shows the average policy assessment scores of the six FIs assessed in the FFA study across five different themes. The institutions assessed include three Thai banks: Bangkok Bank, Krung Thai Bank, and Siam Commercial Bank. Image: Fair Finance Asia

For instance, when assessed against criteria based on global sustainability standards that govern human rights and labour rights, or biodiversity and environment, the six FIs that were assessed only had a consolidated average score of 2.8 out of 10, indicating that they are not doing enough to ensure that their hydropower financing policies uphold the rights of communities and the environment.

Developed in collaboration with Netherlands-based independent research organisation Profundo, and in consultation with national coalitions in Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, the report also reveals regulatory inadequacies at national and regional platforms that have resulted in banks not being held accountable for their lending decisions.

“Communities and CSOs have long raised concerns about the cross-border social and environmental impacts of Mekong hydropower dam projects, especially on Indigenous Peoples and women. The scale of these impacts is so alarming that it begs the question of whether hydropower can even be considered a ‘clean’ and ‘just’ source of power in the region’s energy transition,” said Bernadette Victorio, programme lead at FFA.

Victorio said that it is time for FIs, regulators, and other stakeholders to prioritise cross-border financing models and regulations that prevent and mitigate the actual and potential impacts of these projects, as well as promote responsible hydropower development in line with international standards.

Among the banks assessed, SCB tops the ranking with a consolidated score of 6.1 out of 10. The FFA report also highlights that it is the only assessed FI that discloses a sector policy for the hydropower sector, which identifies some environmental and social risks, such as loss of natural habitat and community land rights. In FFA’s view, all banks should develop and disclose a sector policy for the hydropower sector.

SCB also identifies key mitigation measures, such as impact evaluations on flora and fauna, as well as resettlement plans for displaced communities. As a signatory to the Equator Principles, as it has demonstrated in its recent disclosures, it commits to identifying, assessing and managing environmental and social risks when financing projects, using the International Finance Corporation (IFC)’s performance standards as a benchmark. However, Sarinee reminds that the bank seems to only meet its minimum obligations and has not been responsive to other clarifications that civil society organisations have sought.

In its set of recommendations, FFA suggests that FIs funding hydropower projects take an intersectional approach that considers the specific risks faced by women, children, Indigenous Peoples, and ethnic minorities, who are particularly vulnerable to rights violations.

“The fair representation of such groups during consultations is essential, and companies should develop detailed plans to mitigate the adverse impacts of hydropower projects and devise livelihood strategies that address their different needs.”

A fisherman in Pak Ou Village, Luang Prabang province, Laos. Image: Fair Finance Laos

Stricter thresholds for what counts as ‘sustainable’ in taxonomies: FFA

FFA goes a step further to call on policymakers and financial regulators both at the national and Asean level to take action and improve the transparency and inclusivity of hydropower development plans.

For now, at the regional level, Asean considers hydropower an eligible green category, if a number of criteria are met, which makes it possible for banks and FIs to use hydropower projects as underlying assets for a wide range of sustainable finance tools.

FFA believes that this means that more hydropower projects could emerge, posing more environmental and social risks. It called for the Asean Taxonomy to be improved, including introducing stricter thresholds and technical screening criteria (TSC) for projects, while acknowledging that the provision of a Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) criteria under the taxonomy, used to guide the assessment of sustainable activities for funding to be disbursed, could mean that the overall environmental and social outlook of the hydropower sector might improve.

“

The report from Fair Finance Asia makes the following recommendations:

- Central banks and financial regulatory authorities should make more active use of existing tools and guidelines developed at the regional level.

- Countries that still lack national taxonomies such as Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia, should develop and launch taxonomies following a transparent and inclusive process.

- Regulators shoud encourage commercial banks and asset managers to develop hydropower sector policies.

- Central banks and financial regulators, as well as regional development banks should consider changing their approach to large-scale hydropower based on a more nuanced assessment of their cumulative transboundary and basin-level impacts.

- Central banks should require the banking sector to include material ESG risks, including those related to hydropower, in their credit risk assessments.

- Policymakers should prioritise studies investigating the cumulative impacts of hydropower dams and integrate their findings in national legislation, policy frameworks and strategic planning processes related ot hydropower development.

- Countries in the region should set stricter requirements for dams and hydropower projects, such as those outlined in the European Union (EU) Taxonomy and other credible standards.

- Central banks and national governments should consider introducing incentives for banks and other financial institutions to increase their portfolios of green, social and sustainability-linked financial instruments.

- Central banks should create civil society roundtables, committees or working groups that serve as platforms for dialogue with representatives from a range of research and civil society organisations, as well as community and voluntary groups.

Source: Enhancing sustainable finance in Mekong hydropower: Challenges, opportunities and ways forward

Taxonomies for sustainable finance is an emerging new tool in Asia. Other than the Asean Taxonomy, Thailand has also published its first green taxonomy in June 2023, while Vietnam is developing its own national taxonomy document.

Separately, Laos’ central bank, Bank of the Lao PDR (BOL), is receiving technical assistance from IFC until 2027 as it develops a green taxonomy, among other activities. In 2023, the National Bank of Cambodia also signed a technical assistance cooperation with IFC to develop its green finance taxonomy by 2025.

Sarinee highlighted that the working group for Thailand’s Phase I taxonomy took on board some of FFT’s recommendations, though the alliance still determined that the screening criteria for hydropower are not stringent enough.

A possible improvement would be for the Bank of Thailand, a key member of the working group, to use current or improved criteria and translate them into a disclosure standard for Thai banks, she suggested. “That will move the needle, because then all banks will have to report on the projects they are financing…Taxonomies are voluntary standards and their main objective is to spur green bonds. What is meaningful is how they translate into regulations.”

Shift in discourse: The anti-coal movement as inspiration

Many global energy organisations such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) see hydropower as a sustainable source of energy, particularly as a dispatchable power source that can back up intermittent renewables such as wind and solar. Increasingly, environmental advocates have questioned this view with some arguing that climate change should not be used as a pretext to save the declining industry. Globally, droughts have taken a toll on hydropower over the past two decades.

A key risk that FFT has highlighted with the Luang Prabang dam is how the project is positioned to meet the “growing energy needs” of Thailand, when in fact, the nation is facing a capacity excess. Despite this risk, key players in the Lower Mekong mainstream dam projects, including Thai leading energy producer CK Power, a main shareholder in the company developing the Luang Prabang dam, have aggressively structured loans to move hydropower projects forward.

According to Justpow, an energy watchdog, Thailand’s energy reserve in 2023 stood at 10,000 MW, far surpassing the international security standards. The excessively high reserve margin places a burden on Thai electricity consumers who bear higher costs in the form of fuel tariff charges. PPAs in Thailand are negotiated on a take or pay basis, where Thai authorities pay the power plant operators regardless of whether the electricity is used.

“

The scale of the impacts [of Mekong dam projects] is so alarming that it begs the question of whether hydropower can even be considered a ‘clean’ and ‘just’ source of power in the region’s energy transition.

Bernadette Victorio, programme lead, Fair Finance Asia

CSOs have also highlighted that the shrinking civic space in Asia is a huge challenge, with human and environmental defenders and affected stakeholders who publicly raise concerns about large development projects facing intimidation. Some become victims of arbitrary lawsuits and detentions.

Sarinee also shared that criticising any large power projects in Thailand is almost impossible with the outsized influence of energy and construction companies over the local media. She has had opinion pieces submitted to media outlets taken down. “The media companies rely on advertising for revenue, and these companies are key contributors to that.”

The CSO representatives referenced global anti-coal campaigns and said that the movement to get large-scale hydropower projects eventually on the exclusion lists of major banks will be a long-term endeavour. Sarinee noted how top-tier international banks still do not have hydropower on their exclusion list and said that it would take incremental steps for due diligence to be improved.

Victorio said that FIs providing lending to and investment in the Mekong hydropower sector must consider the rights and wellbeing of communities and ecosystems to ensure the energy transition is just and equitable.

“Sustainable hydropower financing is not just about power generation, but also about creating a lasting legacy of responsible and equitable resource management for future generations,” said Victorio.

Read the full report “Enhancing sustainable finance in Mekong hydropower” here. Fair Finance Asia has also published a new report on fostering a gender-transformative energy transition in Asia.

Interested in topics on fair and just financing? Read other stories here.