Danilo Fernandez, a 63-year-old onion farmer, is worried.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The month of March is the beginning of peak harvest season in the town of Magsaysay, Occidental Mindoro, an agricultural province in the Philippines. Onion prices are unusually low. Fernandez worries that they will fall further.

Unlike last year, there is surplus of onions mainly because the Department of Agriculture (DA) allowed private firms to import as much as 21,000 tonnes of the vegetable, or about 123 per cent of the country’s estimated monthly consumption, in December. Efforts are now being made to prevent the further decline in farm gate prices – that is, the value of a cultivated crop minus the selling costs – as the DA has ordered a temporary suspension of onion imports until May.

“There has always been an under-the-table agreement between big buyers and capitalists who can manipulate businesses to import even when there is no need to. [The government] knows when harvest season is, so they should already know when the time is right to import,” said Fernandez.

Filipinos consume an average of 17,000 metric tonnes of onions per month. Importation is necessary as the supply of locally grown onions cannot meet demand.

A newlywed couple treated guests to giveaways of onions during their wedding reception in the Philippines in January 2023. It was the height of the onion crisis when the cost of the vegetable reached US$14 per kilo – 600 per cent higher than the global average. Image: Aldrik Gohel

It has been a year since the Philippines drew international attention for the price of its onions.

At the start of 2023, prices surged to the point that a kilogram of onions was more expensive than an equivalent amount of beef and chicken.

Fernandez said farmers like himself never benefitted from last year’s price hike. They sold their crops to traders at a low fixed price, but the middlemen resold them to the market for as much as PHP800 (US$14) per kilo, about 600 per cent higher than the global average.

In addition, traders who owned cold storage facilities charged farmers four times more than the regular price, to house the crops at that time.

Last year’s onion shortage was attributed to a series of storms such as Typhoon Nalgae in the last quarter of 2022 that caused damage to farmer’s fields worth up to US$23 million. It was followed by an invasion of crop-devouring armyworms that have become more destructive as climate change brings warmer weather and more unseasonable rains.

The government also blamed “unscrupulous traders and hoarders” for high onion prices. Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos, Jr said that smuggling and an alleged “onion cartel” had undermined the economy.

Since then, key agriculture department officials have been dismissed after investigations into their alleged involvement in crop smuggling. However, an agricultural association stated that even though those involved in supply hoarding and price manipulation had been identified at the Senate hearings last year, nobody was charged.

“Corruption will never change. All we ask is for the government to allow us to dictate the farm gate price so we at least will not bare a loss,” said Fernandez.

Farmers harvest onions during the peak season of March in Bongabon, Nueva Ecija. Image: Frank Cimatu.

Corruption-fighting satellites

President Marcos, Jr prioritised the modernisation of agriculture when he came into office in 2022, even appointing himself as agricultural chief, alongside his elected role as president.

After his first year was marked by steep onion, sugar, and rice prices, he handed the secretary of agriculture position to a fishing tycoon and one of his top campaign donors, Francisco Laurel Jr, in November.

As Laurel grapples with the soaring prices of goods, he has been vocal about focusing on digitising the industry in a bid to stamp out corruption.

The department is endorsing the use of satellite data and space technology to better plan and monitor crop production.

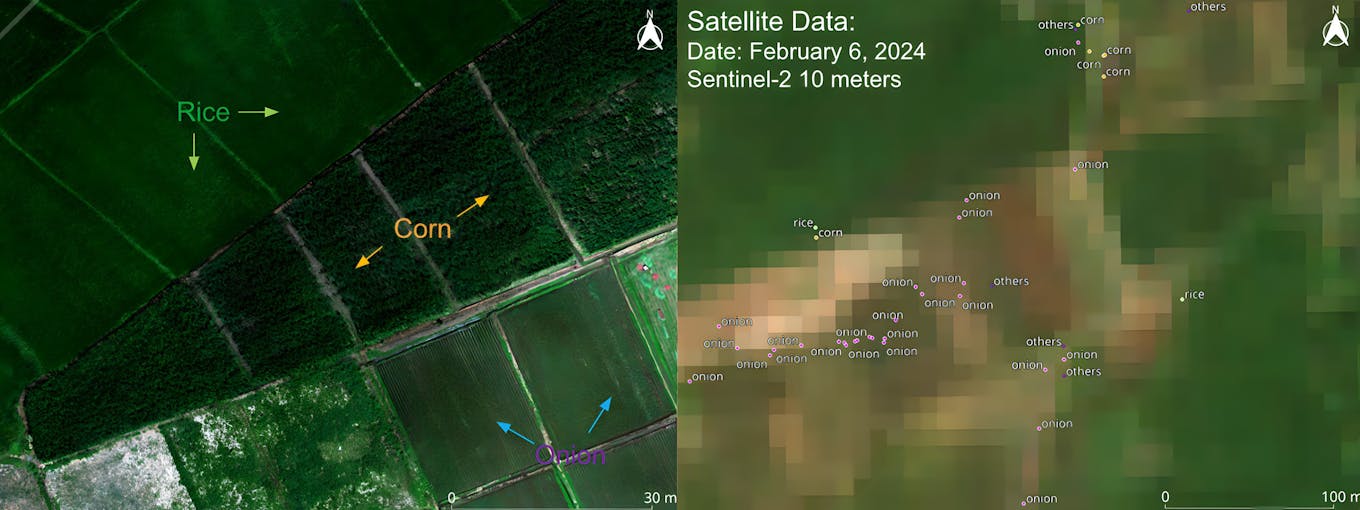

Satellite data showing the state of harvest of onions, rice and corn in Bongabon, Nueva Ecija. The satellite images use a special sensor that can analyse surface features to determine the health of crops. Image: Philippine Space Agency

“Satellite images can estimate the area and volume of onions and other crops at a certain point in time. If government has this near-real time data, it will know where traders hoard their onions and other crops, and act on it to avoid profiteering,” said Arnel Tenorio, interim chief of planning at the Bureau of Agricultural and Fisheries Engineering’s (BAFE) knowledge management digitalisation division.

Unlike the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the country’s primary source of data collection which deploys field sampling to assess crop health and productivity, using satellite imagery is more accurate because it can determine the production of crops planted at any given time, he told Eco-Business.

A collaboration with the Philippine Space Agency (PhilSa) aims to generate satellite imagery to show where farm-to-market roads, should be built. One satellite “can hit three birds with one stone” because it can capture which remote areas are in need of roads, as well as the state of harvest of onions and corn, said Tenorio.

The technology will be used to more accurately estimate when a farmer should harvest and when there is likely to be a production shortfall.

Onions and corn will be monitored in a trial of the technology. Rice is not included, even though it is the staple most crucial to food security in the country.

Data gaps hound the sector

A satellite imaging system already exists for rice montoring in the Philippines. The Philippine Rice Information System (PRISM) was developed by the agricultural department and global research institution Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in 2014.

Despite the maps generated by PRISM that show which areas have abundant rice as well crop damage after a typhoon, the country has continued to suffer from inflation and shortages over the years.

Rice inflation in the country increased at the fastest pace in almost five years in August, reminiscent of a 2018 shock that led to the end of a two-decade-old limit on imports.

The international rice crisis began in the third quarter of last year when India banned rice exports to control rising domestic prices. But it drove global prices higher with Thailand and Vietnam following suit. Rice imports became expensive, which led to an increase in the price of domestic rice.

Satellite technology like PRISM is supposed to help inform the government of production levels in times of crisis. But it is only an alternative means of monitoring rice capacity. The official source of data is still the PSA, but it is riddled with data gaps, said Raul Montemayor, national manager of the Federation of Free Farmers, a non-governmental organisation of 200,000 rural workers in the Philippines.

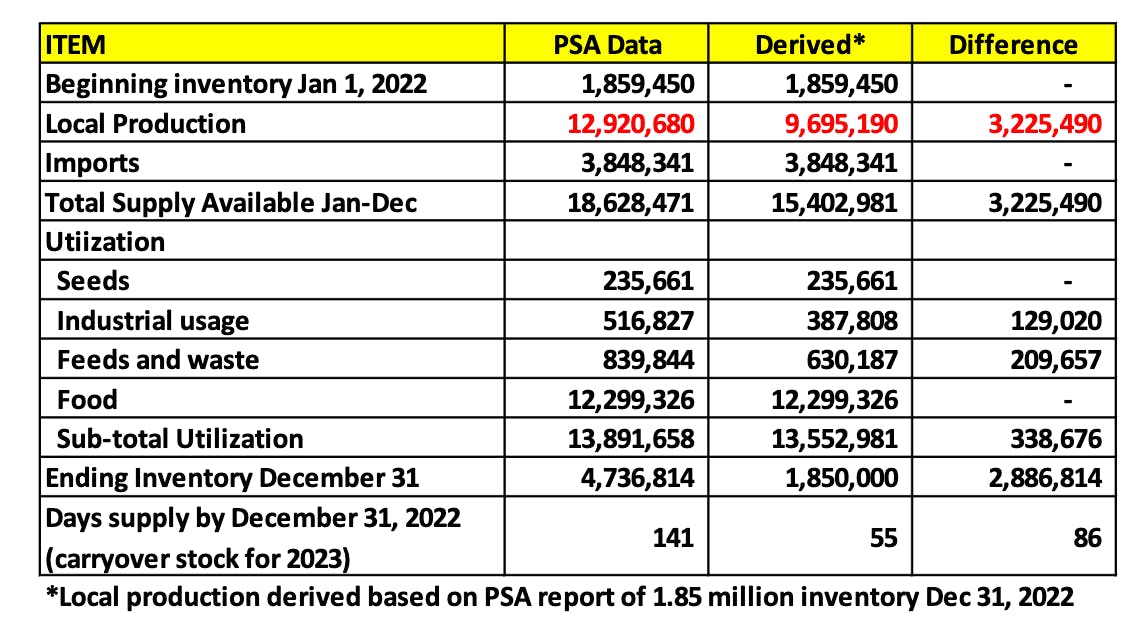

According to a calculation made by the Federation of Free Farmers, there was a 3.2 million tonne shortfall in rice production at the start of 2022, because of an inaccurate projection made by the Philippine Statistics Authority. Image: Federation of Free Farmers

“The rice price hike in the Philippines last year was due to a lack of accurate, timely data, leading to poor programme design, flawed planning, and delayed decision-making,” said Montemayor.

Using data from the PSA website, the Federation of Free Farmers made its own computations that challenged the PSA’s projection that there would be sufficient rice production at the beginning of 2022.

According to PSA data projections, rice production would reach 4.74 million tonnes by the end of 2022, but in reality, only 1.85 million tonnes were left by the end of 2022, said Montemayor.

“If you look at the derived computation which we made, most probably in September we were running out of stock, so that is when hoarding came in. Traders will hold on to stock so prices go up,” he said.

Montemayor wrote to the PSA, pointing out the wide discrepancy in their figures, but the agency replied that it would “continue to develop and perfect our system”.

PRISM, for its part, said it does not directly boost rice production, but indirectly influences it.

“Our main goal is to assist the department of agriculture in making informed decisions for policies and planning by providing timely and reliable rice information. If the department effectively uses our data, it can impact rice production positively,” Clarizza Ann Lagasca, coordinator for PRISM, told Eco-Business.

Tenorio said most farmers were unaware that satellite-based services were available, and were not adviced on the right time to plant.

In Asian countries like Thailand, the government is able to dictate to farmers what they should plant and when because they follow a contract growing system, where private firms purchase farmers’ produce, with the government involved in the facilitating contracts between farmers and buyers.

In the Philippines, it will take “a lot of political will” to dictate agricultural choices to farmers because the sector has no such system, said Juana Tapel, assistant director of BAFE.

Like most developing countries, farmers in the country have to find buyers who will pay them a fair price for their goods. In many cases, they are forced to sell their products at a low price or even give them away because they cannot find buyers, said Tapel.

“[Contract growing] should be the direction for our country. Right now, if you tell a farmer what to farm, but there is no sure buyer, then why will he plant it? It’s a challenge in terms of social preparation. If we don’t programme this well, the problem will continue,”she said.

Getting information to farmers

Even if data is sufficient and technology is in place, it will be useless if the information is not disseminated properly to farmers, said Jose Vidal, president of farmers-based association group Occidental Mindoro Provincial Farmers Action Council.

DA is mandated to install extension workers in each local government unit, tasked to educate farmers on data use to improve their agricultural production and help them market their goods so they can maximise their profit.

“Technical workers like them have to be present, from land preparation until the goods are marketed. They should take the lead in informing farmers when they should plant so as to avoid oversupply. But in reality, it’s like they don’t care,” Vidal told Eco-Business.

There is an average of only one to two extension workers for every municipality of 1,000 farmers, said the agriculture department’s Tenorio. Their work is hampered by limited mobility as public transport and personal motorcycles are used to visit farmers in remote areas.

An extension worker delivers a lecture to rural workers in the Philippines. Image: Department of Agriculture

The extension workers also face a disparity in remuneration between high and low-income municipalities, the inability to discharge the functions of extension workers properly due to a lack of funding, training and professional development as well as low morale and confidence among extension workers, according to a 2020 study by the University of the Philippines Los Baños.

For farmers like Danilo Fernandez, they only meet with extension workers at random times of the year. He recalls the last time he met one was when farmers were given links to read about sustainable farming, which they did not understand.

Fernandez said: “We don’t understand the data handed down to us. That’s why we just end up farming on our own, in the only way we know how.”