Over a 50-year career shipping oil and gas around the world, Hans van Mameren was always an obsessive observer of the weather. Good weather would mean safe passage for his cargo. Bad weather could mean disaster.

But over the last 20 years, as the weather produced more and more surprises, van Mameren started to agonise about the connection between the fossil fuel he was shipping, and the climate it was making less predictable, and more dangerous.

Van Mameren recalls an incident 15 years ago, when a ship carrying oil refinery construction equipment sailed into a storm off the Canadian coast. The captain thought that a depression was behind him, but it freakishly changed course. Suddenly, the ship was engulfed by force 11 winds. No one was hurt, but the ship broke apart and lost its cargo.

“It was not normal, and it made me think how quickly the climate is changing,” says the septuagenarian Dutchman, who launched Singapore-based renewable energy firm Energy Renewed in 2017. The 2014 oil price slump and the oversupply of offshore shipping also played a part in nudging van Mameren towards renewables.

“I have lived a good life. I have worked all over the world. But I wanted to do something for the next generation,” he says.

“

Teenage kids will be vocal about dad working for dirty oil. But the main driver is the writing on the wall [for fossil fuels].

Yan Vermeulen, head, chemical and process industries practice, Odgers Berndtson

Energy Renewed has started a range of ambitious projects, including a plan to electrify one million boats in Southeast Asia. Not all of his ventures have born fruit yet, and the firm is not profitable. But the reward comes from building something with, and for, the young people on his team. If a project doesn’t work out, he pivots to something new. Profits will come, he says.

Hans van Mameren walks along the jetty at Papua Diving, Raja Ampat, where he was working on a project to power the luxury dive resort by renewable energy. Image: Robin Hicks/Eco-Business

Robin Pho pivoted from fossil fuels to renewables in 2018 for similar reasons. The Singaporean inherited his family business in 2008, taking over from his father, who started the oil and gas manpower supplier firm Ponco in West Papua in the early seventies.

When the time came to decide how to take the business forward after the passing of his father, the words of his brother, Roger Pho, who’d left the family business to pursue a different career, stuck in his mind. “He said the business we were in was raping the planet of its resources,” recalls Pho.

That sentiment, and the realisation that oil and gas were industries in decline — clients had started to pay late or not pay at all after going out of business — inspired Pho to set up Right People Renewable Energy.

His company builds renewable energy systems in remote, off-grid locations in Indonesia. Having started out doing single-megawatt projects, the firm is now closing 100MW deals worth more than a million dollars.

Pho says there are two types of people in the energy business: those who’ll never move out of fossil fuels, and believe the industry will be around decades, and those who believe it will be around for the short term, but want to switch to renewables to ride the clean energy wave.

Covid-19 may have added to the number of people in the latter camp. The pandemic has amplified the need for energy firms to transition to clean energy, and as the likes of Shell, BP and Petronas have set goals to decarbonise, more oil and gas executives will be thinking about making the switch.

Executives with children will have particularly itchy feet to change industries, says Yan Vermeulen, head of chemical and process industries practice for recruitment firm Odgers Berndtson and the author of sustainability books for children. “Teenage kids will be vocal about their dad working for dirty oil. But the main driver is the writing on the wall [for fossil fuels],” he says.

Even as demand for energy grows globally in line with population growth, oil demand growth is expected to slow, peaking in the early 2030s. Demand for natural gas will continue to grow until 2035, when it flattens then falls, according to analysis from McKinsey. A report from oil major BP last year suggests that peak oil has passed already.

Meanwhile, renewables are taking off in a serious way. Wind and solar accounted for more than half of new power generation capacity additions in recent years, with solar and wind expected to increase by a factor of 60 and 13, respectively, between 2015 and 2050. Even during the pandemic, green power rose to record levels, increasing by 7 per cent globally.

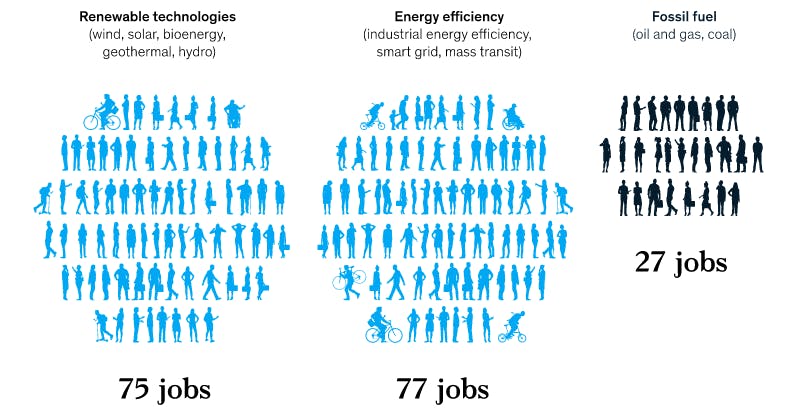

Government spending on renewables creates 50 more jobs per $10 million invested than spending on fossil fuels [click to enlarge]. Image: McKinsey

This means more clean energy jobs. A study by researcher Heidi Garret-Peltier found that government post-Covid stimulus spending on renewables creates five times more jobs per million dollars invested than spending on fossil fuels.

Culture shock

But even so, leaving the oil and gas sector is not always an easy separation. Vincent Bakker spent 9 years working for Shell in the Netherlands, Kazakhstan and Singapore before co-founding a renewable energy finance firm in 2018. He says oil majors not only pay very well, they provide a healthy work-life balance, and champion diversity and inclusion.

Many oil and gas people might experience something of a culture clash, Bakker adds. Renewable energy projects tend to be smaller and localised, which requires small, focused teams working to tight schedules and budgets.

Oil and gas executives may “get a bit of a cold shower” when they make the switch, particularly when it comes to governance, notes Bakker. Oil and gas companies are strict on bribery, corruption and compliance, whereas renewable energy is a bit of a “cowboy” market, with money changing hands in too many ways, says Bakker, who recently departed the struggling startup he left Shell to launch to join a larger renewables firm.

Though oil spills and earthquakes triggered by fracking have long dogged fossil fuels extraction, construction standards are also an issue with renewables, reckons Bakker, pointing to incidences of rooftop solar farms catching fire. “Oil and gas projects are massive, complex installations. Everything has to be perfect. Quality control is relentless. You can’t risk an explosion, so delays are acceptable,” he says.

But Bakker, who was inspired to leave the fossil fuels sector by the plastic crisis and Jakarta’s coal-polluted air, relishes the entrepreneurial side of renewables. “It’s booming. Everyone wants to talk about how to build a new industry. It’s a very fragmented, but super-sociable environment,” he says.

Vincent Bakker (pictured, left) during his time working for Shell. Image: Vincent Bakker

Skills switching

So is changing industries as simple as downing tools in fossil fuels and picking up the same ones in solar or wind?

Brandon Courban is an engineer by training, who started his career with engineering consultancy Mott MacDonald Oil and Gas and now works as a private equity investor in renewables for Olympus Capital. He says oil and gas people, who are used to working on complex mega-projects, shouldn’t find the transition too taxing.

“

Most engineering firms would rather work on renewables projects, even if the margins may be thinner.

Brandon Courban, executive director, Olympus Capital Asia

In some cases, skills are highly transferable, for instance with floating wind farms. Decades of experience in drilling for oil from floating platforms are now being applied to build floating wind power platforms out at sea.

In other cases, less so. A large utility-scale solar plant has a lower manpower requirement, and can be run and maintained to a greater degree using software than, say, an offshore oil rig where the focus is on maintaining the flow of oil out of the ground, says Courban.

More money?

As a general rule in the energy sector, the more capital heavy, long-term projects pay the best salaries, which is why careers in wind tend to pay better than solar, as it’s a slightly more stable sector, says recruiter Vermeulen.

Athough the heyday of oil and gas may be waning, and jobs in renewables are becoming more plentiful as the energy transition hastens, there are reliable rewards for discovering new wells. “If you strike the right field, it will still pay, especially for the short to medium term,” says Courban. A like-for-like engineering job in solar still wouldn’t remunerate as well as oil and gas, he adds.

But though the pay can be good, the number of people willing to embark on careers in oil and gas is shrinking, says Courban. “I don’t know many people who want to work in an extractive industry anymore,” he says. “Most engineering firms would rather work on renewables projects, even if the margins may be thinner.”

But that viewpoint varies, depending where you live. There is less of a stigma against fossil fuels in countries like Indonesia, where millions depend on coal for their livelihoods, and Vietnam, where people want energy independence from China no matter what fuel they use, Courban says.

But even in these countries, attitudes towards fossil fuels are likely to be changing as the market shifts towards renewables. In coal-dependent Southeast Asia, there were just 611,000 jobs in renewable energy in 2016. That number is set to rise to 1.7 million by 2030, based on current energy plans and policies. If the region’s economies accelerate the deployment of renewables — which they are under increasing pressure to — the sector could employ 2.2 million people within the decade.