Private investors from rich nations are profiting from about US$24.8 billion in sovereign bond debt issued by some of Asia’s poorest and most climate-vulnerable countries, according to an analysis made by a London-based research institution.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Sovereign bonds refer to debt securities issued by a national government to raise funds for various purposes, such as financing government spending, infrastructure projects, and debt refinancing.

Ahead of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) annual meetings on 9 October, the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) said that more than 80 per cent of all bond debt is held by private investors in wealthier countries such as investment funds, mutual funds and private banks, based on a 2020 JPMorgan report on growing private investments in emerging markets.

“That figure is likely higher … This is because investors from lower-income countries generally want to invest outside their own borders, so the investors of such developing nations are likely foreigners from wealthy states,” Tom Mitchell, executive director of IIED, told Eco-Business.

Restructuring these kinds of bonds is extremely difficult because most private investors will only accept reduced profits when countries officially default – a lose-lose for both parties, he added.

Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Mongolia, Vietnam and Laos, which have some of the lowest capacities to adapt to climate change in Asia, have sunk deeper into debt as a result of the pandemic, food price rises and war in Ukraine, said IIED.

Many lower-income countries struggle with high debt burdens due to taking out loans or issuing bonds, in order to drive development, added Mitchell, who also served as an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) co-ordinating lead author and a United Nations senior technical advisor.

“They may also be less resilient than rich countries to climate-driven shocks like extreme weather, often they have to borrow still more money to pay for recovery, putting them in further debt and further constraining their ability to pay for, say, education and healthcare due to the high cost of debt repayments,” he said. “Interest rates on debt may also be higher for lower-income countries because they are seen as a greater risk by creditors and investors.”

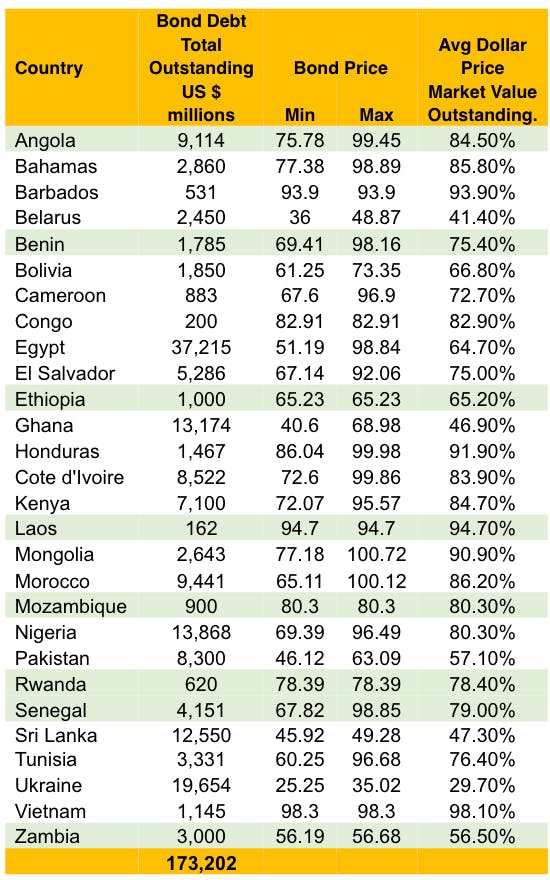

28 poor countries have a sovereign bond debt worth about US$173 billion. The countries highlighted in green above are least developng countries (LDCs). Image: IIED

Sri Lanka has the highest bond debt among the five Asian countries surveyed by IIED, at US$12.55 billion. The South Asian nation, whose exposure to extreme heat and flood events makes it highly vulnerable to climate change, saw its debt increase dramatically over the last five years forcing it to declare bankruptcy in 2022.

Laos, the poorest of the Asian countries analysed, owes up to US$162 million in sovereign debt, while being a hotspot for floods, droughts and other natural disasters.

Elsewehere in the world, the IIED found that least developing countries in Africa are saddled the most from bond debt while suffering from the effects of global warming.

Angola, which has a national debt of US$9 billion, is currently facing the worst drought emergency in the last four decades as a result of climate change, while Ethiopia is one of those most prone to droughts and floods.

“Heavy debt burdens are a major brake on lower-income countries’ ability to tackle the climate crisis, which they have done little to cause and to which they are often more vulnerable than wealthier nations,” said Mitchell.

Although debt has been on the agenda at meetings of the G20 this year there has been little progress in reforming global financial systems to address it, he said, adding that it “makes it even more important for the international community, including the IMF and World Bank, to do all it can to address the spiralling debt burdens of countries on the front lines of the climate crisis.”