Climate hazards are escalating, nations are mired in debt and the costs of food and energy have soared around the world.

Developing countries that are already feeling the financial squeeze are also under pressure to invest in development and climate goals.

These nations will need trillions of dollars in the coming years to invest in low-carbon energy and defences against climate threats.

So far, neither wealthier nations nor private businesses look set to provide this investment in the volumes needed.

Amid this context, a coalition of world leaders and financiers have called for major reforms to the global financial system. This, they argue, will allow funds to flow where they are most needed and, thus, help cut global emissions.

Towards the end of June, French President Emmanual Macron convened a summit in Paris to establish a new “pact” between the global north and the global south which would establish a new, fairer financial system. Some global-south leaders said they wanted nothing less than “absolute transformation”.

Those in attendance agreed that the event fell far short of its lofty ambition. However, it built on the work that development banks and governments have already begun.

Below, Carbon Brief explores the current state of global financial reforms in the wake of the Paris summit – and looks at what experts say still remains to be done in order to channel more money into climate action.

Why was the Summit for a New Global Financing Pact convened in Paris?

Some developing nations are dependent on coal or have economies built around oil-and-gas production. Meanwhile, millions of people in the global south still lack access to electricity and clean cooking fuels.

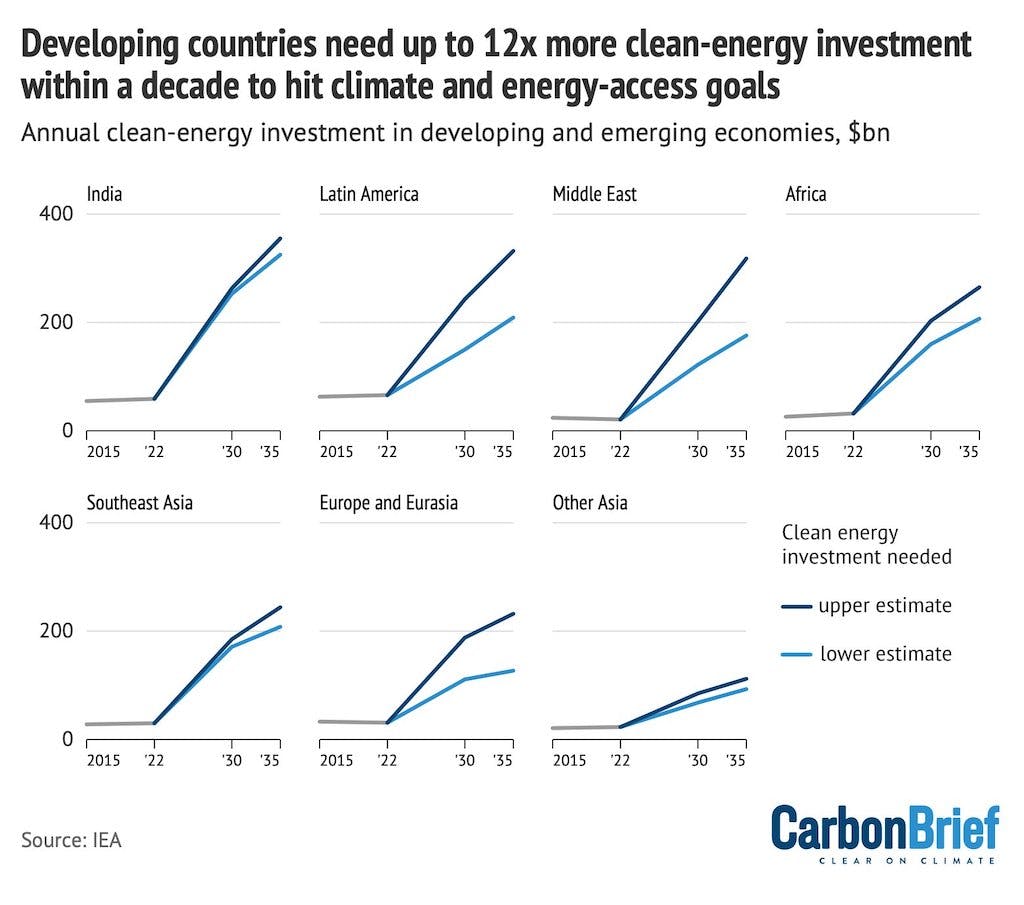

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), spending on low-carbon energy infrastructure needs to grow rapidly by 2030 in developing and emerging economies, if they are to contribute to global climate goals while ensuring sustainable development for their citizens.

“

We need a new financial architecture, where governance, where power is not in the hands of a few people.

William Ruto, president, Kenya

Yet, so far, such investment has remained relatively low, as the chart below shows.

Annual clean-energy investments in emerging and developing economies (shown by region) needed to align with sustainable development and climate goals. The range is derived from two International Energy Agency (IEA) scenarios that meet energy-related sustainable development goals (SDGs), but achieve a different pace of emissions reductions, aligned with the Paris Agreement. The higher bound comes from the Net Zero Emissions (NZE) by 2050 scenario, which limits global warming to 1.5C; the lower bound is from the less ambitious Sustainable Development Scenario. Source: IEA. Chart by Tom Pearson for Carbon Brief.

Speaking at the Paris summit, Zambian president Hakainde Hichilema voiced the concerns shared by many developing country leaders that they lack the financial resources to make these investments:

“When countries are not growing economically, you cannot expect a poor person to carry an additional burden.”

Climate finance, provided by developed countries, is meant to help address these concerns and also help developing nations prepare for the escalating threat posed by climate change. But it has not reached the scale required.

Developed countries have failed to provide the US$100bn in annual climate finance they pledged to hit by 2020. Of the funds they have produced, around 70 per cent have come in the form of loans, which will push developing countries further into debt.

A paper published last month by economists Nicholas Stern, Amar Bhattacharya and Vera Songwe concluded that spending on climate-related development goals in emerging and developing countries would need to quadruple to reach US$2.4tn per year by 2030, in order to meet global targets. (This excludes China, which is already investing heavily in low-carbon technologies.)

Within this, they estimated that US$1tn per year would need to come from “external” sources, including US$500-600bn from private businesses, US$250-300bn from development banks and US$150-200bn from other countries in the form of “concessional and debt-free finance”.

There have been growing calls from world leaders, finance chiefs and activists for major reforms in the global financial system to get these sums of money flowing. Many of these proposals were captured in the Bridgetown Agenda launched by Barbadian prime minister Mia Mottley towards the end of 2022.

Leaders of global-north nations have appeared open to some of these ideas, particularly those that involve reforms to development banks and scaling up private finance.

At COP27 in Egypt late last year, French president Emmanual Macron threw his weight behind the Bridgetown Agenda and announced a summit to advance it.

The resulting Summit on a New Global Financing Pact, held in Paris on 22-23 June, was meant to set a course towards a “new, more balanced financial partnership between the global south and north”.

Its goal was to “lay the groundwork for a new financial system, one that is fairer and more solidarity-based”, which could help the world address climate, nature and development goals. The summit involved more than 40 heads of state, alongside figures from global financial institutions, the private sector and civil society.

One key outcome was a summary by the French chair, which captured the views and wishes expressed by attendees rather than new national pledges. The other was a “roadmap” spelling out key upcoming finance events and what governments and banks should be doing at key points out to the end of 2024, in order to push financial reforms forward.

Yet with just two G7 leaders in attendance – Germany and France – and the global north underrepresented, attendees questioned the extent to which the summit truly represented a “pact” with the global south.

Nearly half the world leaders in attendance were from Africa and many used the event to make their views heard. Kenyan president William Ruto urged Macron to consider a new way of channelling funds for climate and nature outside of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), where he said global north countries ultimately held the power:

“We need a new financial architecture, where governance, where power is not in the hands of a few people.”

While the talks included many big ideas, the outcomes were largely confined to incremental gains, most of which had been agreed prior to the summit. Nevertheless, some observers described it as an “inflection point” and a “first step” on a path to financial-system reform.

How could developing countries get more access to private climate finance?

There is a broad understanding that to raise the trillions of dollars needed for climate finance in developing countries, private businesses will have to play a significant role.

In order to meet climate and sustainable development goals, the IEA estimates that around 60 per cent of clean-energy finance for emerging and developing countries, excluding China, needs to come from the private sector.

This amounts to US$0.9-1.1tn annually by the early 2030s, up from US$135bn today.

As it stands, 81 per cent of climate-related investments in developed countries are funded by the private sector compared to just 14 per cent in developing countries – which are deemed riskier to invest in.

A recent open letter signed by several global north and global south leaders ahead of the Paris summit stressed the need for “enhanced mobilisation of the private sector with its financial resources and its innovative strength”.

Yet private finance has also proved a controversial topic, especially as wealthy countries have not come forward with the amounts of public finance they have promised.

The recent UN climate negotiations in Bonn saw some developing countries and activists argue that developed countries were trying to pass responsibility onto the private sector.

Global north leaders, on the other hand, argue that public money can encourage private investments in developing countries. So far, this idea has not lived up to expectations.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the success of developed countries in mobilising private finance has been “lower than anticipated, with most mobilised in middle-income countries”.

Rising global interest rates and the increased competition for private capital spurred by large subsidy packages in the US and the EU are making this situation even more unbalanced, according to the IEA.

Yet developing nations are still home to plenty of “low-hanging fruit” in the energy transition, according to the IEA. It says every dollar invested in clean energy in developing economies results in 30 per cent more emissions reductions than in advanced economies.

In a report released ahead of the Paris summit, the IEA made several recommendations for scaling up private finance, including strengthening institutions in developing countries. It also called for “significantly larger quantities of concessional finance” to reduce investment risks.

One key issue is that because these countries are considered risky, private investment within their borders is subject to high borrowing costs.

Avinash Persaud, a Barbadian special envoy who was instrumental in devising the Bridgetown Agenda, argues that the markets exaggerate these risks. In response, he has proposed a “partial foreign exchange guarantee” to reduce the cost of capital for developing countries.

This would involve establishing a joint agency between development banks and the IMF, which could reduce costs by hedging currency risks for investors.

(Currency risk is one driver of high borrowing costs in developing countries.)

According to Franklin Steves, a senior policy adviser in sustainable finance at the thinktank E3G, the Paris summit saw limited enthusiasm for such measures. He tells Carbon Brief:

“On private finance mobilisation, all of the ideas and all of the energy is coming from global south countries…What we’re not seeing is any kind of reciprocal energy or drive from the rich countries to really look fundamentally at the way the financial system in the north needs to also be adapted and restructured.”

What are the plans to boost finance from development banks?

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) released a joint “vision statement” at the close of the Paris summit, in which they stressed the need to “adopt new ways of working together”.

These institutions, which play a critical role in providing climate finance to developing countries, have been taking steps towards reform in recent months.

For example, the World Bank announced tweaks to its balance sheet earlier this year to free up US$50bn to lend to developing countries over the next decade.

This measure is part of a wider, G20-backed review of MDBs’ “capital adequacy frameworks” (CAFs), which involves squeezing more money out of their existing funds. (Changing CAFs could allow them to leverage their funds to a greater extent.)

The Bridgetown Agenda emphasised the importance of expanding finance from MDBs to developing countries. There has also been pressure on them to provide concessional finance to relatively wealthy – and high-emitting – middle-income countries, to help them cut their emissions.

At the summit, US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen repeated her view that MDBs should prioritise using existing resources before asking members – of which the US is a key player – for more capital.

The MDBs’ new vision statement says capital increases “could be considered”, but only “following the implementation of all appropriate CAF recommendations”. The French presidency said such CAF measures could free up US$200bn in MDB lending over the next 10 years.

Dr Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, a climate-finance expert at Boston University Global Development Policy Center, says governments will need to “resolve the tension” between their desire to see more concessional finance for both low-income and middle-income nations. This will need to be funded, he tells Carbon Brief:

“A capital increase would resolve this. However, the sequential approach of first implementing the CAF then a capital increase pushes this question down the road.”

Are there any plans to help countries that are struggling with debt?

Around 60 per cent of low-income developing countries are at high risk of or are already in debt distress. This has big implications for climate spending.

Analysis by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) found that, in 2021, 59 nations paid US$33bn in debt repayments while receiving just US$20bn in climate finance from developed countries.

Debt relief has, therefore, become a critical topic for climate campaigners and global-south nations.

There were several new announcements about debt restructuring at the Paris summit However, they were largely incremental rather than the structural changes being demanded.

Perhaps the most significant pledge came from recently installed World Bank head Ajay Banga, who told the audience on the first day in Paris about new measures to help nations dealing with the aftermath of natural disasters:

“Most importantly, [we will] offer a pause in debt repayments so countries can focus on what matters to their leaders when a crisis hits and stop worrying about the bill that is going to come with that crisis.”

The bank will also allow funds it has lent out to be redirected to pay for disaster relief. These measures are particularly valued by small-island states, which have seen huge chunks of their economies wiped out by climate-related disasters in recent years.

Such special pauses on debt repayments were a key component of the Bridgetown Agenda. However, campaigners noted that the World Bank is only offering its “climate resilient debt clauses” for new loans, rather than existing ones as well.

The UK has also announced that it would allow 12 partner countries in Africa and the Caribbean to defer their debt payments in the event of disasters, following a commitment made at COP27. These pauses will apply to both old and new agreements. France and the US also committed to introducing such pauses.

Iolanda Fresnillo, policy and advocacy manager for debt justice at the NGO network Eurodad, tells Carbon Brief:

“The commitments announced by a few public lenders on climate resilient debt clauses…can be a helpful innovation for future lending, but do nothing to address the debt levels in climate vulnerable countries today.”

Meanwhile, Zambia agreed a major US$6.3bn debt restructuring with China and the IMF. This was particularly significant given China’s past hesitance to agree to such deals.

The outcome was seen as a big win for Zambian president Hichilema, who said his country had been a “guinea pig” and he hoped “the lessons of that process can be learned and learned correctly”.

However, there was little concrete action to advance debt restructuring more broadly at the summit. While the final roadmap includes various milestones for further discussions of debt, Steves tells Carbon Brief that the IMF, which is running a “global sovereign debt roundtable” to hash out these issues, was showing “no sense of urgency”.

Other campaigners said debt cancellation would be unavoidable if countries are to find a way out of the current crisis.

What other new sources of finance are being considered?

On top of broader reforms to the global financial “architecture” for channelling climate investment from development banks and the private sector, there is also a need for new sources of money.

Barbadian special envoy Persaud explained in a closing press conference at the event that this money was especially necessary for financing things that do not result in profits, such as the loss and damage driven by climate change:

“We need a menu of three or four international taxes to deal with those things where there are no revenues.”

Several taxes have been proposed. These include a global windfall tax on fossil-fuel companies, levies on shipping and aviation fuel, and a tax on financial transactions.

There have been efforts by Barbados and others to drum up support for all of these taxes. Kenyan president Ruto used a panel event at the summit to urge Macron and other leaders to help establish measures including a financial transaction tax.

In the run up to the event, more than 150 economists and policy experts wrote an open letter calling on leaders to back a tax on the wealthiest 1 per cent to raise trillions for climate action.

Yet only one tax emerged as a viable option at the event – a carbon tax on shipping.

The push for such a tax has been led by the Marshall Islands and the Solomon Islands, which have argued it could initially raise US$60-80bn each year. At the Paris summit, it received backing from around 20 nations, including major ship owners and builders such as Greece and South Korea.

The event was followed immediately by meetings this week in London at the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a UN body, which is hoping to adopt new climate targets.

There, the plans have been facing opposition from Australia and large emerging economies, including China, South Africa and Brazil. Modelling by researchers at the University of São Paulo suggests developing countries would see the biggest economic impact of such a tax.

Other funding streams saw more solid progress in Paris. One of the conference’s major outcomes came from the IMF, when its managing director Kristalina Georgieva announced that developed countries had hit a target to re-channel US$100bn in special drawing rights (SDRs) to help developing countries with climate investment and other challenges.

This US$100bn goal was another component of the Bridgetown Agenda.

However, despite new commitments from France, Belgium and Switzerland, campaigners pointed out that the target would only be achieved if the US’s promised US$21bn contribution is approved by Congress.

Finally, another key announcement from the conference was a new just energy transition partnership (JETP) agreed between Senegal and France, Germany, the EU, the UK and Canada.

Under this deal, the nation will be given US$2.7bn in exchange for increasing its share of renewables to 40 per cent of its installed capacity by 2030. As of 2021, wind, solar and biofuels made up around 25 per cent of Senegal’s electricity capacity, with the majority provided by oil, according to the thinktank Ember.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.