Leaders and experts from the Amazon, the Congo basin and Southeast Asia met in the Republic of the Congo’s capital to discuss their shared issues and opportunities.

At the end of the summit, countries committed to combining resources and pushing for more nature funding in a joint declaration.

But the outcome was “underwhelming”, one observer tells Carbon Brief, and the event was hindered by “quite crap” organisation.

While countries agreed to cooperate closely, “the summit did not lead to a tri-basin alliance as hoped”, conservation NGO WWF said.

According to another observer, the declaration might “inform policies and strategies at COP28” – the UN climate conference in Dubai later this month.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the Three Basins Summit, the main outcomes from the meeting in Brazzaville and the reaction from observers.

What is the ‘Three Basins Summit’?

The purpose of the Three Basins Summit, the second of its kind ever, was to enhance cooperation between countries of tropical forest basins – the Amazon, the Congo and the Borneo-Mekong.

Between them, these three river basins are home to two-thirds of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity and are rich in both fossil and renewable resources.

The summit was organised by the Republic of the Congo and held in its port capital of Brazzaville.

Denis Sassou Nguesso, president of the Republic of the Congo, had called for the summit at COP27 last year.

“

Politically, the main sticking point is, as ever, on finance, and how to generate sufficient funds and get them on the ground in countries to protect forests while helping to eliminate poverty, improve livelihoods [and] bring income to central governments.

Prof Simon Lewis, scientist, University of Leeds

Among the key priorities of the meeting were increasing finance for protecting natural forests in the Three Basins, outlining guidance for a carbon market and establishing a “road map” towards regional governance and cooperation.

More than 60 countries were expected to send representatives to the meeting, including 16 from the Congo basin, nine from the Amazon and five from the Mekong, as well as tropical forest countries from the Caribbean, Central America and Africa.

Morocco – convenor of the first summit – the US, EU, Association of Southeast Asian Nations and African Union were also expected to participate.

No heads of state from Amazonia and Asia were present at the meeting, Afrik21 reported – despite previous pledges to attend from Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and French president Emmanuel Macron. In the end, both chose to only send video messages for the high-level leaders’ segment on the last day of the summit.

Brazzaville was also the host of the original Three Basins Summit in May 2011, which had seen more than 35 countries participate.

That summit yielded a 13-point declaration that mandated the president of the Republic of the Congo to facilitate an agreement between all basin states to cooperate on climate, biodiversity and sustainable development.

In the 12 years since the first summit, there has been some progress towards regional climate cooperation, building alliances among basin states and securing finance for biodiversity conservation.

In 2016, three climate commissions – one each for the Congo Basin, the Sahel region and African island states – were established as part of an initiative led by the COP22 Marrakech presidency. These commissions were set up to act as the focal points to coordinate climate action in all member states of the African Union.

COP22 also saw a proposal to establish the Blue Fund for the Congo Basin, which was created in 2018 and co-financed by 16 African member states. It currently hosts a pipeline of projects amounting to US$13.6bn meant to serve climate, sustainable development and regional integration goals.

In November last year, Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo announced an alliance on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Indonesia that campaigners dubbed the “Opec for rainforests”.

The three countries agreed to work towards negotiating “a new sustainable funding mechanism under the provisions of the Convention on Biological Diversity”, while also agreeing to advocate for “results-based payments” to stem deforestation and conserve existing forest carbon stocks under a new climate finance target for 2025.

A month later, forests got their own entire section in the COP27 cover decision, a historic first. The COP27 cover text referred to reducing emissions from deforestation, but also alludes to “joint mitigation and adaptation approaches”.

Weeks later, at COP15 in Montreal, countries agreed on a global deal for reversing biodiversity loss in this decade and a financial mechanism to support tropical forest nations.

To the organisers of the Three Basins Summit, these developments “confer responsibility and legitimacy on the world’s three forest and biodiversity ecosystems to define and implement the decade’s operational roadmap for preserving forests and biodiversity”.

In the wake of these meetings, Nguesso announced that his country would host a summit to provide a “space to encourage richer countries to contribute financially” to protect basin regions, Reuters reported earlier this year.

What were the main outcomes of the summit?

Financing

Finance for climate action and conserving biodiversity was one of the central pillars of the summit.

Tropical forest nations have historically and collectively demanded that their countries be paid for reducing deforestation and maintaining their forests as carbon sinks, while calling for existing and new funding mechanisms to support this.

The final declaration, which listed seven commitments, included that the countries would “encourage financial mobilisation and the development of traditional and innovative financing mechanisms”.

It said that developed countries must “urgently” meet their international finance commitments, including to provide US$100bn per year in “new, additional, predictable and adequate resources” for climate finance and to mobilise US$200bn per year for biodiversity action by 2030.

The declaration also reiterated the need for both a loss-and-damage fund to help global-south countries deal with the impacts of climate change and a commitment from developed countries to provide 0.7 per cent of their gross national income in official development assistance.

Oscar Soria, the campaign director at Avaaz, notes that the declaration marks the “first time that countries of these basins, in a united front” are calling on developed countries to realise their commitments to climate and biodiversity finance. He tells Carbon Brief that the “encouragement of financial mobilisation” was one of the “crucial steps” made at the summit. He adds:

“The big question is how the nations of the Three Basins will use that declaration, which is very specific on calling for funding, but very general on what are the actions that will take place to protect their forests.”

Prof Simon Lewis, a global-change scientist at the University of Leeds and University College London, tells Carbon Brief:

“The complexity here is that countries are quite different, for example, with Democratic Republic of the Congo losing 500,000 hectares of forest a year, but driven by poverty, which is a very different situation compared to Brazil or Indonesia.

“Politically, the main sticking point is, as ever, on finance, and how to generate sufficient funds and get them on the ground in countries to protect forests while helping to eliminate poverty, improve livelihoods [and] bring income to central governments.”

Carbon markets

One of the summit’s key objectives was to put in place the architecture “for the creation of a sovereign carbon market on a global scale” to allow “fair remuneration for the ecosystem services produced by the Three Basins”.

A “sovereign” carbon market is one that allows countries to trade carbon credits generated from projects reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, known as REDD+. The UN developed REDD+ in the late 2000s as a way to help developing countries preserve their forests and is part of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The Coalition for Rainforest Nations has pushed for such a “sovereign carbon” market at COP27 and at other international meetings.

However, UN REDD+ credits are currently excluded from Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement, which allows countries to voluntarily trade “mitigation outcomes” for use towards their Paris pledges.

Several observers tell Carbon Brief that carbon and biodiversity offset and credit markets “dominated” the summit.

In a draft version of the summit declaration, “sovereign” carbon markets were the only option for financial mobilisation explicitly mentioned.

The draft called for countries to turn to the private sector to “develop” such a market, account for biodiversity restoration as an activity that could generate “premium sovereign carbon” credits and support compliance to make such a market “bankable”.

It suggested the creation of a carbon market based on the “polluter pays” principle, where the party responsible for emissions pays for damage to the natural environment. The draft set out a floor price of US$30 per tonne for REDD+ credits and US$70 per tonne for internationally traded mitigation outcomes, which was subsequently missing in the final version of the declaration.

Savio Carvalho, the global campaign leader for food and forests at Greenpeace International, tells Carbon Brief that a “sovereign” system to set carbon credit rules between basin countries and trade collectively with other countries around the world could be a “path to hell” without international accountability. He adds:

“If there is any mechanism required, they need to have an architecture that has scrutiny at the highest level and not just some countries having this deal among themselves.”

However, Carvalho tells Carbon Brief that there were some dissenting voices – “even the World Bank”, which spoke out against relying too much on carbon markets. He adds:

“There was also David Cooper [acting executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity], who also said that there are other options also on financing and we need to look at the other options, too.”

In the final version of the declaration, all explicit mentions of a sovereign carbon market were removed. The document instead alludes to developing “innovative financing mechanisms” and a “sustainable system of remuneration for ecosystem services provided by the Three Basins”.

Deforestation

Deforestation is a widespread issue for tropical forests in the Amazon, Congo and south-east Asian regions.

The Brazzaville summit “provided a good start on important discussions about the future of these forests” and finding solutions to issues such as deforestation, the WWF global forests lead, Fran Price, said in a statement. She added:

“Going forward, it will be important to have more robust representation and high-level leadership from all three regions and a more structured discussion on topics such as how to collectively tackle drivers of deforestation, [and] promote restoration and sustainable forest management.”

In the Three Basins Summit declaration, countries reaffirmed their commitment to “combat deforestation”, with an added caveat that this does not remove the need to cut greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels.

More than 140 countries previously pledged to “halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030” at the UN climate summit COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo were among the signatories.

However, one year on from the pledge, there have been no major meetings to make progress on the pledge nor any organisation set up to push it forward, Climate Home News reported.

At COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh last year, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Brazil and Indonesia were not among the 26 countries that committed to an initiative to build on the 2030 pledge.

A recent report from the Forest Declaration Assessment found that the world is off track to halt deforestation by the end of this decade.

On the sidelines of the Brazzaville summit, the European environment commissioner, Virginijus Sinkevičius, signed a roadmap for the implementation of the EU-Congo forest partnership. This is an EU initiative aimed to help forested countries protect their forests and ensure sustainable trade under the requirements of the EU’s deforestation law.

In a statement, Sinkevičius said the roadmap will progress talks in “addressing deforestation and forest degradation in Congo and working towards a sustainable forest economy”.

Soria tells Carbon Brief that “increased awareness about the significance of tropical forests and the urgent need for their protection” was one of the main positive takeaways from the summit. He adds:

“Additionally, the focus on inclusive governance involving Indigenous peoples, youth, and civil society indicated a holistic and inclusive approach to forest conservation.”

South-south cooperation

The Three Basins Summit was supposed to define and adopt how regional governance and cooperation across the Three Basins on climate and biodiversity would work and to set up a roadmap and work programme to get there.

Arlette Soudan Nonault, the Republic of the Congo’s environment minister, said at the summit that “joining forces is an absolute necessity”.

The final declaration recognised the need to “pool and capitalise on existing knowledge, experience, resources and achievements in each of the basins”. It also “recognise[d] the value of enhanced cooperation between the Three Basins” and called for the development of solutions together at “the institutional, diplomatic, legal, scientific, technical and technological levels”.

Lewis says that “scientific cooperation was one important strand of the talks”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Very positively, on the margins of the summit, scientists from the region launch[ed] the Congo Basin Science Initiative, inspired by the successes of Brazilian science, to drive investment into the region’s science and scientists. This could, in time, end some of the major data deficits in this crucial part of the world.”

The summit was “a good initiative” to coordinate between the states of the Three Basins, says Bonaventure Bondo, a youth climate activist and the coordinator of the Democratic Republic of the Congo-based advocacy group Youth Movement for Environmental Protection (MJPE-RDC). But, he adds:

“The absence of some of the people from Amazonia and south Asia certainly had an impact on the quality of the collaboration. We wanted to see all the leaders from the Three Basins gathered around a table to reflect on a common position to defend and to build a real coalition to protect the ecosystems of the three forest massifs in the world.

“This attitude leads us to believe that the resolutions of the Three Basins Declaration will be difficult to implement.”

Soria tells Carbon Brief that “while there was enthusiasm for international collaboration…there was also frustration due to the lack of a formal alliance and specificity in shared goals.” He continues:

“Clearly, there’s no shared understanding on the specific direction and goals of this coalition, although there’s a political will to work together, at least in the rhetoric.”

According to Africanews, participants at the summit “expressed their desire for these meetings to occur regularly”.

In a speech on the final day of the summit, Kenyan president William Ruto announced that his country will end visa requirements for all African countries by the end of the year. Ruto also called on other African nations to work to similarly reduce barriers to cooperation, trade and travel.

Fossil-fuel extraction

In the days leading up to the summit, the environmental research and advocacy group Earth InSight released a report highlighting the dangers that fossil-fuel extraction poses to tropical forests.

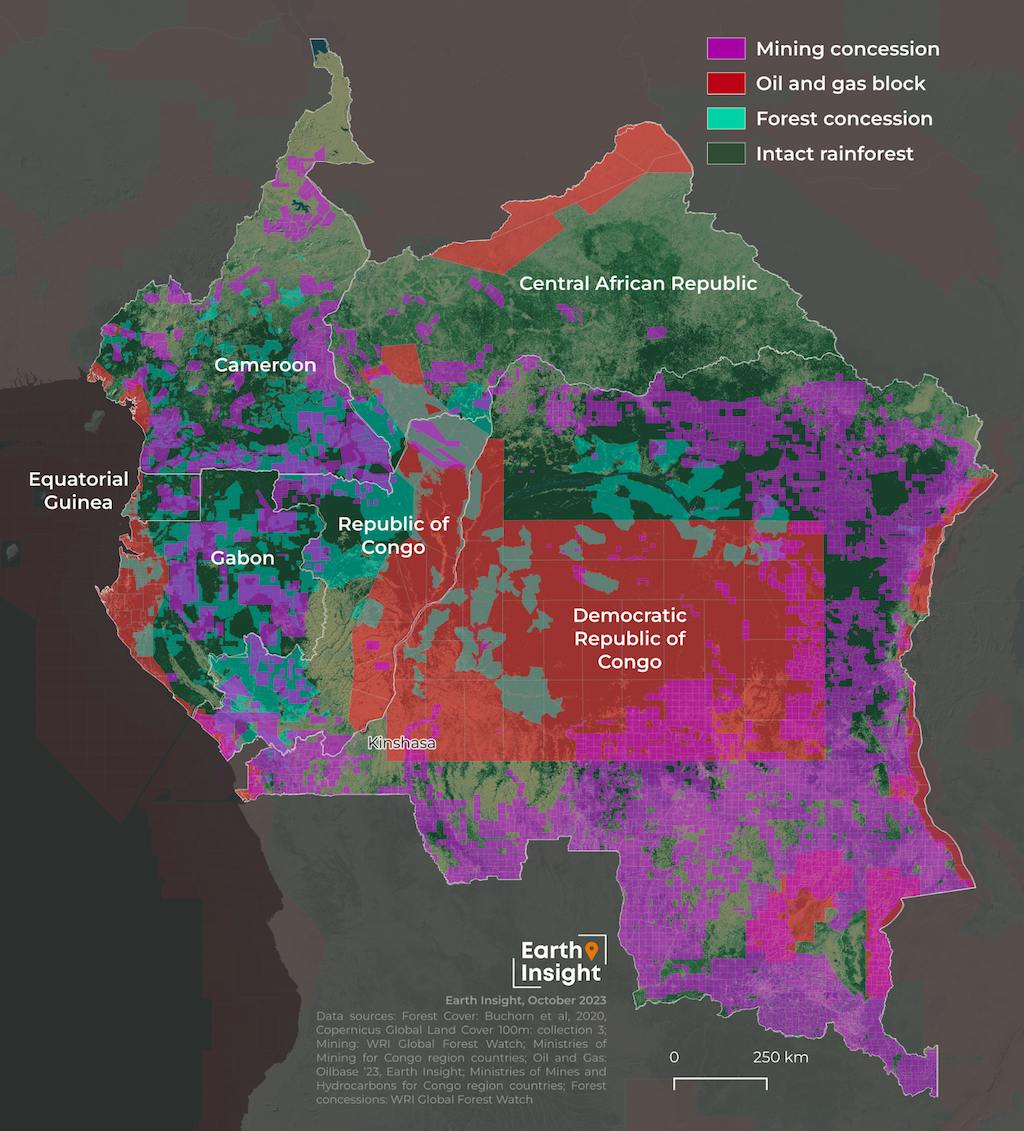

The report, based on official government publications, satellite observations and field data, found that nearly 20 per cent of intact tropical forests across the Three Basins overlap with “active and potential” fossil-fuel concessions. Nearly one-quarter of the intact forests are within mining concessions.

A map of the Congo basin, showing areas of mining concessions (magenta), oil and gas blocks (red), forestry concessions (light green) and intact rainforest (black). More than 72m hectares of undisturbed tropical moist forests in the Congo basin now overlap with oil and gas blocks. Credit: Earth InSight

The report stressed the need to end deforestation and degradation, adding:

“Without a halt to extractive activities – and adequate protection and enforcement, the remaining forests and the Indigenous and local communities that depend on them will continue to be severely impacted.”

More than 60 environmental, human-rights, youth and Indigenous advocacy groups signed a joint statement ahead of the summit welcoming cooperation between the basins. However, it added, the groups were “deeply concerned” with the summit’s focus on carbon markets and a lack of attention paid to Indigenous peoples and environmental defenders.

The statement included a call to “halt and reverse” ecosystem degradation due to “large-scale agriculture, mining, extractives and other industries, such as through a global moratorium on industrial activities in primary forests as well as priority forests”. Additionally, it highlighted the need for a just energy transition and low-carbon development in tropical forest nations.

Ultimately, no mention was made of the impacts of fossil fuel extraction in the summit’s final declaration.

Bondo, whose group MJPE-RDC was one of the signatories of the open letter, tells Carbon Brief:

“Our message has never been well received, because we denounce those companies that violate the rights of communities and destroy our planet for their own selfish interests…We deplore the fact that the African states have not taken clear and concrete decisions to stop all industrial and extractive activities in the forests of the Three Basins.”

Indigenous rights

The crucial role of Indigenous peoples and local communities in protecting forests was cited by many observers as a key part of any discussions and outcomes at the summit.

Indigenous peoples’ territories and protected areas play a “vital role” in forest conservation in the Amazon. Indigenous peoples protect as much as 80 per cent of the world’s biodiversity and manage or have tenure rights to more than one-quarter of the world’s land.

A statement from Greenpeace in the lead-up to the summit said that recognising the “fundamental role” of Indigenous peoples and local communities in maintaining forests “is of the utmost importance”. It added:

“Any proposal to conserve these forests that does not integrate the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Africa, Latin America and Indonesia cannot succeed.”

A letter signed by different Indigenous and frontline organisations called on the Three Basins governments to make a number of commitments, including greater recognition of forest communities’ lands and upholding the right of communities to “fully and effectively” take part in decisions for planned developments.

The final declaration from the summit committed to involving “all states and national authorities, including Indigenous peoples” and others such as local communities, young people and non-governmental organisations “in an inclusive manner”.

The role of Indigenous peoples, women and youth in ecosystem management was also discussed at panels during the summit.

The declaration failed to secure “concrete actions” around the “rights and livelihoods” of Indigenous peoples and local communities, Greenpeace said in a statement after the summit.

Soria says that the emphasis on the involvement of Indigenous peoples and local communities “could pave the way for more inclusive and sustainable forest management practices”.

However, Carvalho tells Carbon Brief that he feels Indigenous peoples and youth voices were not sufficiently included in discussions over the three days.

He says there should be “fewer closed doors or more listening and conversation spaces” at future summits. He adds:

“Governments need to ensure that young people and Indigenous communities are not just sitting there, but they are actually involved in the conversations and in the solutions.”

Similar discussions arose at the Amazon Summit in Belém, Brazil in August. The Belém Declaration, which resulted from that summit, said that the active participation and respect of the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities is crucial to advancing a new common agenda for the Amazon.

It established an “Amazon Mechanism for Indigenous Peoples” to “strengthen and promote dialogue between governments and Indigenous peoples in the Amazon region”.

Road to COP28

Reuters reported that experts and policymakers at the Three Basins Summit “discussed shared priorities” ahead of the upcoming UN climate summit COP28, due to begin later this month in Dubai.

The concept of using ”nature-based solutions” to mitigate and adapt to climate change has entered the forefront of discussions around meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement in recent years.

One target of the Kunming-Montreal agreement reached at the COP15 biodiversity summit last December aims to restore 30 per cent of degraded ecosystems by 2030. Ecosystems – such as forests, wetlands and rivers – are natural carbon sinks.

At the climate summit COP27 last November, several countries put forward new global initiatives aimed at stopping deforestation and restoring ecosystems.

Participants told the Brazzaville conference that they hoped the three regions would share unified views at COP28, according to Africanews. Bondo, the youth climate activist, tells Carbon Brief that the summit was useful to “consolidate collaboration” between countries across the Three Basins. He adds:

“It was important for the basin states that make the world breathe to have the same message for the next COP28, and to ensure that the forests they use to save the world bring benefits to the local and Indigenous communities that depend on them.”

He says he hopes that COP28 results in “less talk and more action in favour of the protection of forests and the communities that live in them and depend on them”.

Lewis tells Carbon Brief that “cooperation across Amazon and Congo basin countries was an important stepping stone to COP28 and the vision of tropical forest-rich countries having common policy positions” – although he notes that there was a lack of participation from south-east Asian countries. He adds:

“Common positions would give forest-rich countries more leverage in international negotiations.”

But Carvalho from Greenpeace does not believe that the tropical forest countries will share “one voice” in Dubai. He tells Carbon Brief:

“They have done the groundwork, they have garnered support…They now need to build on that foundation between now and COP30 [so that] at least by the time we are heading towards Brazil [the expected host of COP30 in 2025], this initiative is strong and it’s based on a different paradigm.”

Soria says aspects of the Brazzaville declaration around financial mobilisation and payments for ecosystem services “will likely emerge in the COP28 negotiations”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The discussions and commitments made in Brazzaville can inform policies and strategies at COP28. The disappointment from the lack of a formal alliance might serve as a catalyst, prompting nations to work harder toward consensus.”

What was the reaction to the summit’s outcomes?

The summit’s outcome was “underwhelming”, with “no major breakthroughs” achieved, Carvalho says. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There was lots of pomp and all that goes with it, lots of grandstanding and laughter and fun. But, at the end of the day, where do we go from here? Do we have a concrete pathway? There was a lack of clarity on that.”

One success from the summit is that it “managed to garner pan-Africanism in the space”, he adds, especially around forests and nature conservation. Around a dozen African heads of state attended the summit. He says:

“While they haven’t got horizontal Three Basins collaboration, they’ve got quite a horizontal and vertical pan-African buy-in that we need to save the forests and we need to invest in nature protection.”

Soria echoes that sentiment, telling Carbon Brief that “the absence of all heads of state of the Amazon basin and the Borneo Mekong basin countries made this summit an African summit in essence”. He adds:

“While it’s a positive step for the region to start a dialogue to build common positions on biodiversity, climate and land, it lacks that global geopolitical appeal that could build enthusiasm among donor and developed nations.”

The fact that the summit was unable to achieve a “formal alliance” highlights “the complexities involved in aligning the diverse interests and policies of the participating nations”, Soria says.

In a statement released after the summit, Greenpeace called out the final declaration, saying it “fails to commit to any concrete actions for the protection and restoration of nature”.

Greenpeace continued by pointing out that the focus on “controversial” carbon markets “will only reinforce the commodification of nature and human rights violations if they become the primary such mechanism” for funding conservation.

In addition to the lack of concrete outcomes, the summit itself had a very full schedule and the “logistics were quite crap”, Carvalho says. Many parts of the summit were “utter chaos” with poor organisation and “no space” for civil society to meet, he says.

Another observer tells Carbon Brief that the organisation of the summit was “a mess”.

Ultimately, Soria says, the summit can be regarded with a “mix of hope and disappointment”. He adds:

“Despite the limitations, the summit initiated crucial discussions and commitments for future forest preservation efforts. The declaration, which includes a seven-point plan, disappoints in specificity of actions and commitments from the countries that are part of the Three Basins.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.